Space junk could be tackled by housekeeping spacecraft

- Published

Spent rockets represent some of the largest, most dangerous space junk

Scientists have proposed a viable solution to the growing problem of space junk.

The idea involves launching a satellite to rendezvous with the largest space debris, such as spent rocket bodies.

The satellite would then affix a propellant kit, driving the debris to its doom in the Earth's atmosphere.

The authors claim the scheme, in the journal Acta Astronautica, external, could inexpensively remove five to 10 such objects per year of operation.

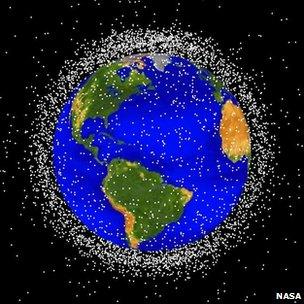

The scope of the problem is enormous; more than 17,000 objects of a size greater than 10cm reside in low-Earth orbit. But the greater problem on the horizon is that each of the largest of these represents the potential to create thousands more.

"In our opinion the problem is very challenging and it's quite urgent as well," said Marco Castronuovo, the Italian Space Agency researcher who authored the paper.

"The time to act is now; as we go farther in time we will need to remove more and more fragments," he told BBC News.

In 2007, China demonstrated an anti-satellite system, destroying one of its own defunct satellites and creating 2,000 extra bits of debris in the process. More recently, a collision between US and Russian satellites created even more.

What is feared is a kind of chain reaction, called the Kessler syndrome after the Nasa scientist who first described it in 1978, external, in which fragments hit other fragments which in turn hit more, creating a cloud of debris that will make vast swathes of low-Earth orbit completely unusable.

The debris presents a risk not only to other man-made satellites in orbit, but occasionally also to the International Space Station and manned space missions.

Space politics

The new research identifies more than 60 objects at a height of about 850km, and two thirds of those weigh more than three tonnes each - many moving near a speed of 7.5km/s. Most of these largest threats are spent rocket bodies, and it is there that Dr Castronuovo thinks the effort should begin.

Low-Earth orbit is an increasingly crowded space

"It's difficult from a political point of view; many of these objects belong to nations that are not willing to co-operate or do not allow access to their objects even if they are at the end of their operative life, and there is no international regulation on who should remove the objects that are left in space," he said.

"If we start concentrating on the spent rocket bodies - which do not have sensitive equipment on board -it should not pose any problem to the owner to give permission to remove them; and there's no doubt they are not operative anymore."

Dr Castronuovo proposes a scheme in which small satellites are deployed on seven-year missions, each with two robotic arms: one to intercept a rocket body or failed satellite and hang on, and another to affix an ion-engine thruster that will drive the debris out of orbit.

The satellites would then release the debris, hopping from one to the next in a choreographed dance with five to ten large objects per year.

"The proximity operations and manoeuvring talked about here is not easy, but the technology is getting there for that; the idea that you go and attach yourself to something in orbit is becoming more credible," said Stuart Eves, principal engineer for Surrey Satellite Technology.

"People have come up with all sorts of daft ideas... that are really science fiction at the moment. Something like this is a lot more practical."

Nevertheless, the greater problem may be political, as any proposal struggles to be seen as a purely aimed at space junk, Dr Castronuovo said.

"This kind of approach could be seen as a threat to operative systems; if you have the power to go to an object in space and pull it down, nothing prevents you from going to an operative satellite and pulling it down, so it's really a delicate matter."

- Published28 June 2011