Harrabin's Notes: Solar shadowed

- Published

In his regular column, BBC environment analyst Roger Harrabin asks why solar power is failing to light up the developing world.

SOLAR SHADOWED

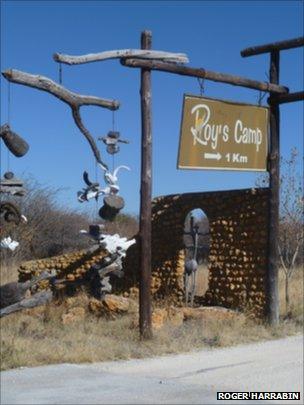

Roy's Camp is a popular stop-over on the overland route from Cape Town to Victoria Falls

Roy's Camp near Grootfontein in northern Namibia is a popular stop-over on the dusty overland route from Cape Town to Africa's biggest cascade, Victoria Falls.

The campers' shower block has steaming hot water. The upmarket travellers enjoy cabins with electricity.

But in a place blessed with 300 sunny days a year and up to 10 hours' sunshine a day, none of the power here to illuminate the visitors' lives or sluice the dirt from their skins is produced by the sun.

It is typical of many of the world's most sun-drenched nations where solar power has been slow to take off, despite the high hopes of environmentalists.

The World Energy Council statistics for 2008 show Namibia had just 0.3 megawatts (MW) of solar electricity generating capacity. Chilly Canada had 100 times more, whilst grey-skied Germany leads the world with 5,877 MW.

In other words, solar panel numbers are determined primarily by energy politics and prices, not sunshine. In sun-blasted Australia, for instance, investment in solar has not been able to compete with ultra-cheap coal power.

In Namibia, the electricity at Roy's Camp comes from the grid which draws on South Africa's huge reserves of coal energy.

The hot water for the showers comes from another rival to solar; a wood-fired boiler known inexplicably as a "donkey". The wood supply from what they call "invader bush" is sustainable in much of rural Namibia because the population density is so low and the bush is taking over agricultural land anyway.

"Some people talk about solar power but I'm not interested," says a member of staff at Roy's Camp.

"The donkey is fine. It gives hot water whenever we want to fire it up, whereas if you have a solar water system you only get hot water in the evening which wouldn't please all our guests.

"The electric power on the grid is easy. Solar electric might pay me back sometime but it's a long pay-back and it's not for me."

Feeding the donkey with wood

Namibia defines the scale of the challenge for solar energy enthusiasts. It has a tiny population of 2.1 million, is relatively wealthy by African standards and it needs more power.

A study by the United Nations Development Programme noted: "With an average daily solar radiation of 6 kilowatt-hours per sq m, Namibia's solar regime is among the world's best and holds huge development potential."

But several issues have held back what might have been a solar boom in south-west Africa. Experts say one factor is the dominance of the South African grid and traditional ambitions from government and industry to expand grid connections.

Another is the previously high tax on imported solar panels. There are also said to be high installation costs and poor facilities for maintenance.

The government is trying to remedy the dearth of solar photovoltaics, and in a recent speech, the energy minister proposed it as a solution for remote areas without grid connections.

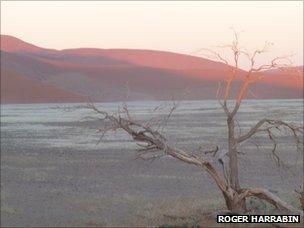

Namibia's government wants to boost solar power

A recent law mandated solar water heating on the rooves of government buildings and offered incentives for solar. This has encouraged an eight-fold increase in stand-alone photovoltaic (PV) capacity, rising from a tiny base. Solar water pumping capacity for isolated systems has risen nearly five-fold and solar thermal capacity has boomed twelve-fold.

But the potential is far greater. So it's a disappointment to environmentalists that the government hasn't extend the solar mandate to the many expensive offices and homes springing up in the capital Windhoek and in the German enclave of Swakopmund where wealthy South Africans come for sea fishing.

"Solar water heating should make total sense for many people in a country like Namibia," Elena Nekhaev from the World Energy Council told me. "All you need is something containing water that's connected to the pipework.

"Solar photovoltaic is a different case. Costs may be coming down but it still costs five to 10 times more than, say, coal. Then you have issues of whether expert maintenance is available and the need to keep the panels clean in a dusty country like Namibia.

"It may be a good solution for remote areas where you could put in a couple of panels, but it doesn't look like a large-scale solution."

Dust makes solar panels hard to keep clean in Namibia

Meanwhile the really ambitious solar plans for Namibia are on the back burner. Three years ago plans were revealed for the Greentower - a breath-taking £100m, and nearly a mile high (1.5km) chimney surrounded by greenhouses that, heated by the sun, would create an updraught to turn power turbines.

It would be almost twice the height of the world's tallest man-made structure.

The Namibian government offered to pay half the bill for a E0.5m (£0.43m) feasibility study into this extraordinary project. But the inventor has not yet been able to raise his share of the cash.

A global study by McKinsey predicted that if pv energy continues on its Moore's Law curve of plummeting costs and increasing efficiency, solar will be genuinely competitive in sunny countries like Namibia within the next few years. But for a while at least, it looks as though many Namibians will remain wedded to their donkeys.