Has physics become cool again?

- Published

In his column for the BBC News website, science correspondent Pallab Ghosh looks at what's behind the increase in A-level students studying physics at university.

The award winning comedy show Big Bang Theory celebrates rather than derides "geeks"

Figures published this morning, show an increase for the fifth consecutive year in the number of students studying A-level physics. According to the Institute of Physics, for the first time since 2002, physics is back in the top ten most popular subjects.

The total number of students entered for physics A-level has increased by 6.1%, from 30,976 in 2010 to 32,860 in 2011. Applications for physics courses at university are also up by more than 17% on last year and astronomy is up by a whopping 40%.

Commentators believe that this increase is partly due to students thinking more about their future employment prospects - but some suggest that the surge in interest may be because physics has become "cool" again.

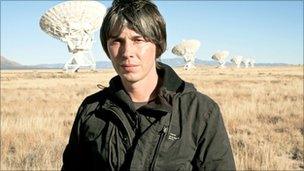

The stereotype image of the physicist as socially inept individuals with bad haircuts and no dress sense has made way for "geek chic" epitomised by Professor Brian Cox and his hugely popular Wonders of the Solar System and Universe series.

The president of the Institute of Physics (IoP), Professor Sir Peter Knight talks about the "Cox effect" inspiring a new generation of physicists. But IoP policy analysts, such as Tajinder Panesor, were taken aback by the huge rise in applications for physics courses this year.

"To be honest with you we don't really understand that. We're delighted, but we can't quite put our finger on why that is," he says.

University applications for all courses are up in general, most likely because many students have chosen not to have a gap year because of the rise in tuition fees next year. But science and engineering courses are especially popular.

The Cox Effect: Inspiring a new generation of Physicists

Higher tuition fees are likely to be a major factor in students opting for courses that are more likely to get them a job.

But that doesn't fully explain why physics and astronomy in particular are so much more in demand than other science based subjects.

One professor of physics and science broadcaster, Jim Al-Khalili, believes that there has been a groundswell of popular interest in those subjects over the past few years which have been fuelled by more science coverage in the media.

"What has helped tremendously is that the BBC decided to designate 2010 as their Year of Science and commissioned across a number of channels lots of new science programmes such as BBC1s prime time Bang Goes the Theory, Brian Cox's programmes on BBC2 and that's continued into this year," he says.

That view is born out by Helena Bennett, who is hoping to get two A's and an A* to get a place at Imperial College London.

"Things like the (Large) Hadron Collider, the God particle (Higgs boson) and the space programme have had a lot of time on the news and when these things come on the news people really go for it," she says.

But as well as increasing interest, the media has helped to change attitudes toward science in general and physics in particular. The US comedy The Big Bang Theory celebrates physics and all things "geeky" rather than derides them.

"It's not embarrassing any more to say I'm a theoretical physicist at a party," says Professor Al-Khalili. "The geeks are on the march again!"

And a fellow physics professor, David Franklin, concurs: "I think people's view of physics has changed in a range of ways. I think there's a 'geek chic' thing and one factor that springs to mind here is the growth of companies like Apple who are very much about pushing back the boundaries of technology and bringing science to the public," he says.

Images from the Hubble Space Telescope give a new insight into how the Universe works

Professor Franklin is starting a new physics course at Portsmouth University beginning this year. Bradford University and St Mary's University College in Twickenham are investigating the possibility of starting courses in 2012. This reverses the trend of the closure of physics departments over the past 15 years. There were once 72 across the country now there 46.

The new courses are beginning in response not just to growing interest from students but also greater demand from local employers.

However, Dr Neil Bentley, deputy director-general of the Confederation of British Industry said the trend was promising but there was a long way to go: "We're encouraged that more people have heeded the call from businesses to study A-Level maths and science, but overall numbers are still far too low and must increase further to meet employer demand," he says.

"There is already a skills gap emerging in this area with over 40% of companies saying they are having difficulty recruiting people with science, technology, engineering and maths skills."

The director for the Campaign for Science and Engineering, Imran Khan also says we shouldn't get too carried away by these results.

"Despite physics breaking into the top 10 A-levels subjects this year, we've only just got back to 2002 levels in terms of entries. An international comparison of 24 countries showed that England, Wales, and Northern Ireland were the only ones in which fewer than 20% of students study maths post-16. We desperately need to keep up the momentum," he says.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external