Map tracks Antarctica on the move

- Published

Scientists have produced what they say is the first complete map of how the ice moves across Antarctica.

Built from images acquired by radar satellites, the visualisation details all the great glaciers and the smaller ice streams that feed them.

The map has been published online by Science magazine, external.

It should aid the understanding of how the White Continent might evolve in the warmer world being forecast by climatologists.

"This is like seeing a map of all the oceans' currents for the first time. It's a game changer for glaciology," said lead author Dr Eric Rignot.

"We are seeing amazing flows from the heart of the continent that had never been described before," added the US space agency (Nasa) and University of California (UC), Irvine, researcher.

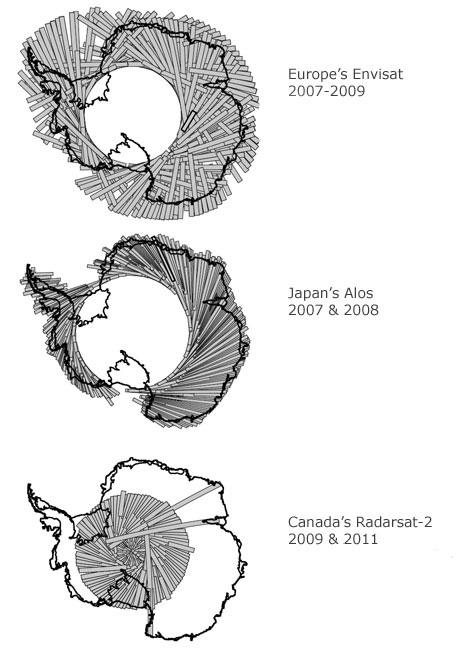

The map incorporates billions of radar data points collected between 1996 and 2009 by satellites belonging to Europe, Canada and Japan.

Ice drains from the interior via huge glaciers that calve icebergs into the sea

It closes previous data omissions, especially in the east of the continent.

"We designed acquisition plans, switching on and off the satellites, in all the right desired geographic locations so we could fill the gaps we didn't have data in before," explained Dr Mark Drinkwater from the European Space Agency. "That was a mammoth effort," he told BBC News.

Dr Drinkwater praised in particular the contribution of Canadian company MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, which rolled its Radarsat-2 spacecraft every time it flew near the pole to get a view of the ice surface at the highest latitudes. "That was the only way we could fill the so-called 'data hole' that satellites traditionally don't see," he explained.

Ice movement is detected using a technique called Satellite Radar Interferometry (InSAR), which compares images from repeat passes over the same location.

InSAR will pick up even subtle deformations in the ice sheet resulting from slow creep. That said, some areas of Antarctica are moving very fast.

Ice velocities on the new map range from just few cm/year near places where the ice divides into different paths, to km/year on fast-moving glaciers and the ice shelves that float out from the edges of the continent.

The sprinters are Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in West Antarctica. This region, say the authors, is also the part of the continent "experiencing most rapid change at present, over the widest area, and with the greatest impact on total ice sheet mass balance".

Recent survey work has revealed that Pine Island, for example, is thinning rapidly; its surface has been dropping by more than 15m per year.

The oldest data comes from the European Space Agency's ERS satellites

Other fast-moving streams include the Larsen B glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula. These glaciers experienced an eightfold increase in speed when the floating ice shelf that bounded them collapsed in 2002.

Although the broad picture of how the ice drains from the centre of Antarctica to the edges has been reasonably well characterised for some time, the map throws up a number of previously unrecognised features. These include a new ridge that splits the 14 million square km landmass from east to west.

The map will be useful in monitoring change over time, by comparing it to past and future measurements.

It should also assist the calibration of the computer models that are used to forecast how the ice sheet will react to changes in the climate and the surrounding ocean. The models will need to reproduce the sort of behaviour seen in the map before scientists can have confidence in their ability to predict the future.

One aspect they need to simulate better is the length of some of the ice streams, which stretch much deeper into the interior of Antarctica than many people had acknowledged.

The map work was completed as part of the 2007-8 International Polar Year (IPY), a concerted programme of research to investigate Earth's far north and south.

As part of that initiative, a lot of effort was also put into mapping the rock bed of Antarctica.

Understanding conditions at the sheet's base, which can slide on liquid water, is a key part of the equation that describes how the ice mass above will move.

Radar mapping: Key work was undertaken by several spacecraft, with Radarsat-2 imaging the central region of Antarctica

- Published9 August 2011

- Published20 June 2010