JWST faces its own hubble, bubble, financial trouble

- Published

- comments

Should we be surprised by the latest assessment of how much it will cost to build, launch and operate the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)? Documents sent to the US Congress by Nasa indicate the final bill will now be $8.7bn.

But if you spend annually what the US space agency spends on this telescope project and you don't launch until 2018 - that's about what you come out with. Those close to the project have been saying this for some months, so the new assessment is not a shock disclosure.

Nonetheless, the figure is now laid out for all to see, and at a very difficult time. The House Appropriations Committee has already declared that it would cancel the project given the chance, and the autumn is likely to see some pretty fierce argument and lobbying as politicians debate the future of "Hubble's successor".

The Senate has some heavy-hitters who've already come out in support of the telescope. These include Barbara Mikulski, external, whose state hosts the Nasa centre running Webb, and who campaigned successfully to get Hubble a fifth and final servicing mission even after that cause seemed lost.

JWST could be made cheaper if more money was spent now and it was readied ahead of 2018, but the cash flow isn't there to pursue this strategy.

Nasa has promised to lay out a financial plan for Webb as part of its 2013 budget request at the start of next year.

The problem facing the agency is that in doing JWST, it is now struggling to do other things; and the ever excellent Eric Hand in Nature has an interesting article running this week, external that suggests every quarter of the American space programme will have to make a contribution to fund the observatory.

It was Nature magazine, of course, that penned the article with the famous headline "The telescope that ate astronomy, external". It must feel that way to those whose projects have already paid the price for JWST overruns.

US scientists would like to launch a space telescope to map the distribution of dark matter and trace the influence across the cosmos of the equally mysterious dark energy. This telescope, called WFIRST, is deemed the number one priority (after JWST) for the American astrophysics and astronomy community. But they can't even begin to contemplate such a mission so long as Webb continues to suck funds out of Nasa's science budget.

For its part, the US space agency claims that JWST is finally on track - that it now has the right management structures in place to see the project through and that all the major technical obstacles on this grand venture have been overcome.

Seventy-five percent of the mass of the telescope is in production or complete, says prime contractor Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems, external.

You'll have seen evidence of that last week in the UK where the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), one of Webb's four flight instruments, completed three months of tests in a cryogenic space chamber. It will now be sent to Nasa's Goddard centre in Maryland for eventual integration into the observatory.

And for me now, it's this international dimension that I will be fascinated to see develop over the coming months… because JWST is not some private grief the Americans can simply close the door on; the project is a collaboration with Europe, external and Canada. There are consequences outside the United Sates if Webb is cancelled; there are promises and commitments that would be broken.

The US has already left Europe high and dry on several projects this year. In April, it walked away from three multi-billion euro missions-in-the-planning, forcing European scientists and engineers to head back to the drawing board after three years of feasibility work.

Europe is still waiting for a clear commitment from the Americans to collaborate on joint missions to Mars in 2016 and 2018. If that commitment is not forthcoming in the next month, both opportunities could fall.

And this where I get a little parochial and talk about British interests in the Webb project. It is not just that the STFC's UK Astronomy Technology Centre, external (UKATC) is leading the European team developing MIRI; it is also that British astronomers will be heavy users of JWST, if and when it flies.

If you look at Hubble observing opportunities, it is UK scientists that have traditionally taken the largest block of time on the telescope after their American peers. Again, we saw evidence of that last week when Exeter University was awarded 200 hours on Hubble, external to study the atmospheres of planets around distant stars.

So, strap yourself in; this is going to be a bumpy ride. James Webb is already caught up in a lot of politics that has nothing to do with space and astronomy, and right now it's anyone's guess as to how this story might turn out.

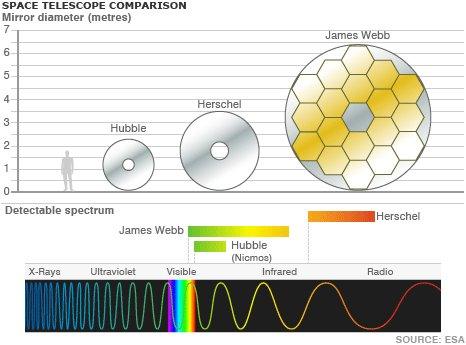

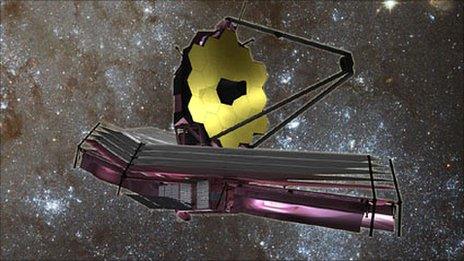

James Webb will be tuned to see the Universe in the infrared, and at longer wavelengths than Hubble. Its mirror will be bigger than the one launched on Europe's Herschel space observatory

- Published23 August 2011

- Published18 August 2011

- Published7 July 2011

- Published11 November 2010

- Published20 October 2010