Dark matter hinted at again at Cresst experiment

- Published

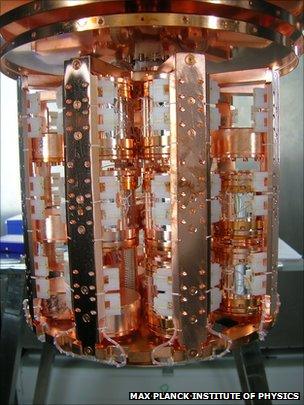

The Cresst experiment is held at fractions of a degree above absolute zero

Scientists may have seen more hints of the dark matter purported to make up a majority of the mass in the Universe.

Researchers at the Cresst experiment in Italy say they have spotted 67 events in their detectors that may be caused by dark matter particles called Wimps.

The finds must be reconciled with other experiments that have recently hinted at the detection of Wimps.

The results were revealed at the Topics in Astroparticle and Underground Physics meeting in Germany on Tuesday.

They have also been <link> <caption>posted on the physics website Arxiv</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1109.0702" platform="highweb"/> </link> , complementing the data of other "direct detection" experiments.

Dark matter was initially proposed to explain how galaxies hold together; from what we know about how gravity works, much more matter is required to hold galaxies together than we can see.

Many candidates for what dark matter actually is have been proposed, but most explanations have been refuted by experiments.

What seems to align best with both theory and experiment so far is a class of particles that tend not to interact with the matter we know: weakly interacting massive particles, or Wimps.

Though dark matter is imagined to be everywhere, permeating the Universe and clumping around galaxies, it is estimated that some Wimps may pass through our entire Galaxy without interacting with any normal matter.

Dark materials

Cresst is just one laboratory dedicated to catching the flighty particles in deep underground detectors.

It uses 33 lumps of a crystal called calcium tungstate. When a Wimp smashes into an atomic nucleus within the crystals, the experiment is designed to see evidence both of a phonon and a photon - the sound and the light of the interaction.

The Cresst team says that in their experiments between 2009 and 2011, they have seen 67 such events that cannot be explained by other means.

The data are at a level of certainty of more than "four sigma" - strong suggestions, but still shy of what can formally be called a discovery.

They add to the weight of results released by other facilities, such as Dama, housed like Cresst in the National Laboratory of Gran Sasso in Italy, or the Cogent experiment in an abandoned mine in Minnesota, US.

Earlier in 2011, the Cogent experiment <link> <caption>reported that the events that they see</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1106.0650" platform="highweb"/> </link> vary each year with the seasons - <link> <caption>exactly as the Dama facility found in 2010</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1002.1028" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

That is consistent with the idea that as our Solar System moves through the dark matter halo surrounding our Galaxy, the Earth is sometimes moving with and sometimes against this current of dark matter.

However, the exact nature of the Wimps the Cresst team thinks it sees - in terms of how much they weigh and how likely they are to interact - does not seem to agree well with those earlier results.

In fact, earlier this week Xenon, another direct detection experiment at Gran Sasso, <link> <caption>published results in Physical Review Letters</caption> <url href="http://prl.aps.org/accepted/L/a807fY08Q5915b30a3cb1110670f26f541cf0b391" platform="highweb"/> </link> suggesting the experiment had not seen any Wimps of the sort seen by the others. Yet there is some controversy about the interpretation of the results, which were <link> <caption>first published in April</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1104.3121" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Dan Hooper, a dark matter researcher at Fermi National Laboratory in the US, said that such controversies reflected the difficulty of pinning down a particle whose properties were not yet known.

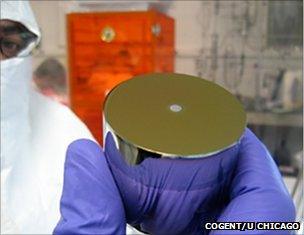

The Cogent experiment uses cylinders of germanium to hunt for Wimp interactions

Each experiment is looking for a tiny "ping" in a cacophony of events caused by stray light, normal matter particles from space, and even radioactive decay within the experimental apparatus.

"These regions of various experiments doing various things all move around a bit, depending on who's doing it and how - there's some subjectivity in this," Dr Hooper told BBC News, adding that any ambiguities should be cleared up as each experiment gathers more data.

"Both Cogent and Cresst are data-starved; if they had twice as much data, we'd know twice as much stuff.

"But given all the uncertainties in the detectors, the velocities of the Wimps and other factors like that, it seems plausible to me that all of these can fall into line with one another.

"I'm not saying Cresst has seen the smoking gun; but it's one more, different kind of experiment seeing a similar sort of signal. I'm very encouraged by this."

- Published29 June 2011

- Published25 February 2011

- Published14 January 2011