Nasa unveils Space Launch System vision

- Published

Nasa's top official, General Charles Bolden, hails the beginning of the post-shuttle era

The design for a huge rocket to take humans to asteroids and Mars has been unveiled by the US space agency Nasa.

The Space Launch System (SLS), as it is currently known, will be the most powerful launcher ever built - more powerful even than the Saturn V rockets that put men on the Moon.

On top of the SLS, Nasa plans to put its Orion astronaut capsule, which is already in development.

The agency says the first launch should occur towards the end of 2017.

This will be an uncrewed test flight, and it is estimated the project will have cost $18bn (£11.4bn) by that stage.

"The next chapter of America's space exploration story is being written today," said Nasa's top official, General Charles Bolden.

"President Obama has challenged us to be bold and dream big, and that's exactly what we do.

"While I was proud to fly in the space shuttle, tomorrow's explorers will dream of one day walking on Mars."

Evolved design

The SLS will borrow many technologies developed for the recently retired space shuttle programme. These include the shuttle orbiter's main engines.

But whereas the reusable spaceplane had three such power units on its aft, the SLS main core stage in its full-up configuration will have five.

A further stage on top will provide additional muscle, as will shuttle-like strap-on boosters. Although, again, these will be bigger than those used on the shuttle.

The initial design calls for the SLS to be able to put 70 tonnes in a low-Earth orbit (LEO), the altitude of the space station. Some 130 tonnes is the eventual target.

By comparison, today's biggest commercial launch vehicles, such as the Ariane 5 or the Delta IV Heavy, can put just over 20 tonnes in LEO.

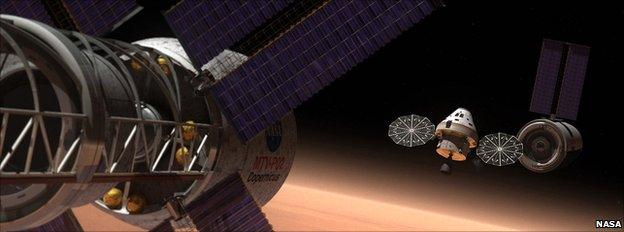

The immense lift capability is necessary to put all the equipment in orbit that is needed to undertake a deep-space mission. This would consist of not only the Orion capsule but perhaps a habitation module and a landing craft to go down to the surface of another planetary body.

In the case of a Mars mission, several SLS launches would probably be needed.

Destination 'roadmap'

Wednesday's announcement is the culmination of months of study on the part of Nasa engineers, and sometimes fractious argument with the US Congress which felt the agency was not moving fast enough on the project it initiated in a piece of legislation called the Nasa Authorisation Act 2010.

"We have been frustrated by the time delays," said Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, a Texas Republican who serves on a Nasa oversight committee and who joined Charles Bolden on Capitol Hill to make the SLS announcement.

"The numbers are within the authorization levels; we are now moving forward as a team for America," she added. "Sometimes the making of the sausage isn't pretty but we are at the right end, I hope."

Since the retirement of the shuttle in July, America has no means of getting its own astronauts into orbit; it must rely on Russian Soyuz rockets to do that job.

Nasa has invited the private sector to sell it transportation services to the space station, but these commercially operated rockets and capsules will not be ready for flight until the middle of the decade. And, in any case, none of them will have the power or the life-support systems capable of taking astronauts beyond LEO.

In leaving routine LEO operations to the commercial sector, Nasa hopes it will have sufficient funds available to develop the SLS and Orion in time for the 2017 inaugural launch.

There is no "roadmap" yet for where the SLS and Orion might take humans, and when. President Obama has talked only about getting astronauts to an asteroid in the 2025 timeframe, and to Mars at some unspecified future date.

Other targets might include missions to geostationary orbit to fix broken, high-value telecommunications satellites that sit 36,000km (22,370 miles) above the Earth.

"We've talked conceptually about multiple destinations," said Bill Gerstenmaier, Nasa's Human exploration and operations associate administrator. "We need to get some more details on the actual rocket performance, put that together with these concepts and then start talking to people about specifics.

"We can do pretty exciting missions with the capability we've got, even in the 70-metric-tonne range."

To send a manned mission to Mars, even just to circle it, would require a lot of support equipment

- Published25 May 2011

- Published21 July 2011

- Published11 October 2010

- Published8 July 2011