Balloon goes up for geo-engineering - but that's the easy part...

- Published

- comments

Representatives discussed the proposed project at the Science Festival in Bradford

I'm not too keen on raising the same kind of point in successive articles, but the news that UK scientists are to trial an innovative piece of geo-engineering kit within a couple of months begs some of the same questions that came up in Monday's piece on carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The most basic one is simple - money.

One end of the hose will be attached to a balloon floating a kilometre up in the air.

The other will be tethered to the ground, with a pump pushing water up the pipe so it will spray out at the top.

This and other investigations that the UK team is performing will cost in the region of £1.6m ($2.5m).

And much larger sums will become necessary if and when bigger experiments are needed - because the eventual aim of this would be to get into the stratosphere, tens of kilometres above our heads.

And what comes out would probably not be water but tiny particles of sulphate dust, mimicking the cooling effect of volcanic eruptions.

For sure, technical research is needed to explore the potential of different forms of geo-engineering - as it is with CCS.

But the technology is, for both geo-engineering and CCS, probably the easiest piece of the puzzle.

As I discussed on Monday (and thanks as always for your comments on it), the big issue with CCS is that it costs more to generate electricity - and as things stand now, why would anyone bother?

(The kicker is that the CO2 can be used to bring up more oil from wells that are approaching the end of their conventional commercial life, which does pay for the carbon capture but will in the end lead to more CO2 entering the atmosphere - but that's another story.)

We're also in a grey area regarding regulation.

Under whose water

If you're an island nation and you want to store carbon dioxide in the rocks under your feet, in all probability that's going to be OK.

But what about if the storage sites lie in geological formations that extend under a neighbouring state, as could well be the case in much of Europe, for example?

And putting it under the seabed has already raised questions under the London convention on dumping at sea.

These obstacles are even clearer with geo-engineering.

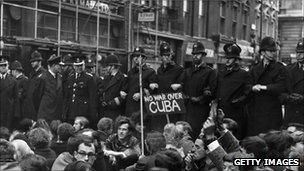

There were protests against the nuclear stand-off between the US and Russia with Cuba in 1962

How would schemes like this be funded in practice?

Who would regulate them?

What would be the mechanism that arbitrates between conflicting interests when something goes wrong - if injecting particles into the stratosphere over Russia, for example, were to neuter the South Asian monsoon?

Given that some large-scale experiments could bring adverse impacts, how are they to be overseen - even if it's agreed that they should happen?

There have been a couple of international agreements (at the UN biodiversity convention last year, for example, when governments agreed there should be no geo-engineering schemes that damage nature, external).

But the big questions remain unanswered - even, largely, un-discussed.

Go back to the 1960s, and the biggest threat in the minds of many governments was nuclear war.

For sure, technologies were developed to fight it and to survive it.

But in parallel, governments and societies asked and answered some of the social questions.

The answers may not have been convincing and may not have been pretty, because nuclear war is possibly the ugliest prospect that has ever confronted humankind.

But at least discussions were had - and some of them, between governments in private, eventually led to disarmament.

Now, there are voices, some of them at the top of politics, who will tell you that climate change is the biggest threat facing the human race.

If it is, the social and political discussions that need to happen and reach conclusions around the topic of geo-engineering ought to be happening now - in parallel with the technical research, if not ahead of it.

Critical Path Analysis tells you that you should begin the longest part of a composite task first, in order to reach the conclusion as soon as possible.

The hurdles that CCS and especially geo-engineering present, along with the finance question, are almost certainly more challenging than the technical ones presented by carrying one end of a hosepipe up on a balloon and spraying some water out.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external