What does Tevatron closure mean for big US science?

- Published

The Tevatron was a world-leading high-energy physics facility until the LHC took the baton in 2009

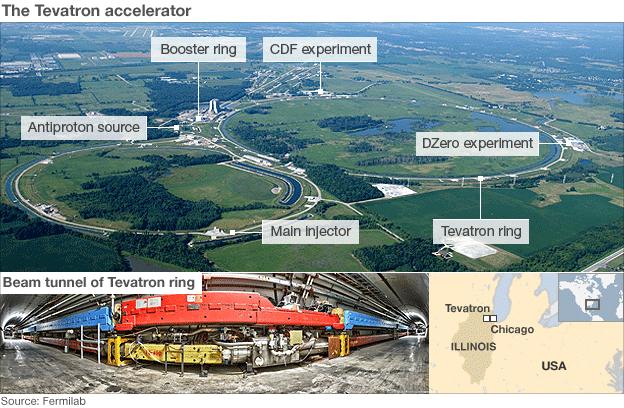

The last stores of particles circling in the Tevatron this week are in fact a quiet concession: the US has for the moment to cede its dominance in particle physics.

But what does the Tevatron's closure mean for the state of big-ticket American science?

One might think, with the space shuttle programme coming to a close and fitful negotiations for the James Webb Space Telescope ongoing, that perhaps America is slowly pulling down the shutters on its dominance across a number of disciplines.

Patrick Clemins, director of the research and development budget and policy programme at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, sees it a different way.

"I don't think people would say that American science is on a downward trend," he told BBC News.

"I think what people would say is that we are experiencing a lot more competition than we have in the past. A lot of countries have learned from our growth over the past decades and are implementing some of the same policies to grow their own scientific infrastructures."

He added: "It's not so much a sense that the US is falling behind, it's that everyone is catching up."

Funding bullseyes

So how to maintain if not dominance, then at least relevance in a world where new nations are building vast telescope arrays, starting independent space programmes and striking deals for fusion energy facilities?

The Tevatron will be upgraded to a high-intensity leader, instead of a high-energy one

What almost everyone agrees is that international collaboration is the key in an era when it takes a machine the size of a Large Hadron Collider (LHC) to break frontiers.

"I think what's happening is that these big-ticket items are just so big that no country is doing it alone," said Rob Roser, who heads up the CDF collaboration, one of the two giant detectors at the Tevatron.

"In the old days, the US built the Tevatron all by itself," he told BBC News. "But to build the next machine, that won't be the case - we'll need help from everybody."

The LHC has set an impressive precedent for this kind of international buy-in, but two well-known problems stand in the way of the US playing host to facilities that require international financing.

One is that budgets for science endeavours are most often decided on a yearly basis. What is promised as a decade of annual funding one year can be whittled down the next, or shot down altogether.

"When you look at Nasa and individual missions that cost hundreds of millions each year, those are large budget items that Congress sees," explained Dr Clemins.

"When they're looking to cut the budget, those programmes definitely have a bullseye on them."

Low security of funds may scare off international collaborations, but heightened security at the borders is another stumbling block.

Immigration restrictions that have come into force in the past decade have made it particularly difficult for non-US scientists to gain the easy access that visitors to other big global facilities might find.

In short, as Dr Roser puts it: "To be successful in the long run in terms of international projects, we have to be better international players."

'Hard problems'

A more troubling perspective on the politics that may be behind an apparent decline in US dominance in science comes from Rush Holt, a member of the US House of Representatives - and the only PhD-educated physicist in Congress.

He brings up what has always played a role in America's willingness to spend eye-watering sums of money on cutting edge research: national pride.

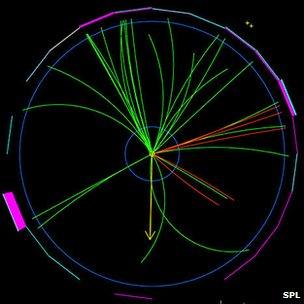

The top quark discovery was just one of many that put physics' "Standard Model" on firm footing

He recalled the story of Bob Wilson, a leader of the Manhattan Project who was drafted in to run a world-beating particle accelerator project - that would become Fermilab - before ground had even been broken.

Called before Congress to justify the huge expenditure, he was asked by Senator John Pastore what the facility would do for national security.

He famously answered that it had "nothing to do directly with defending our country except to make it worth defending".

"This is the first time that the US, in my half-century of experience, seems to be saying that we're lowering our sights," Mr Holt told BBC News.

"It's not a particular project that fails to find the political support to keep going, but the whole enterprise.

"That's hard for me to accept, having grown up in a country that has always wanted to push the frontiers, always wanted to be the pace-setter, whether in physics or biology or packaging or you name it."

Off Capitol Hill and back at Fermilab, physicist Dan Hooper hopes Mr Holt is wrong.

"It's one thing if we make a strategic decision that some particular corner of science is being done very well by the Europeans or Chinese or whoever, and therefore we are going to invest in this other place where we think we can get more bang for our buck - those sorts of considerations should be made," he told BBC News.

"But if it's a matter of 'we don't do that any more because it's hard, or it requires resources'... If we had thought that way all along, we would never have done the Tevatron, would never have done the Apollo programme, would never have done many of the great scientific achievements of this country.

"I want us to be attracted to the hard problems that, when they're solved, will be remembered for a very long time."

- Published1 July 2011

- Published7 April 2011