Rocket launches Chinese space lab

- Published

The Tiangong-1 space lab was launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in the Gobi desert

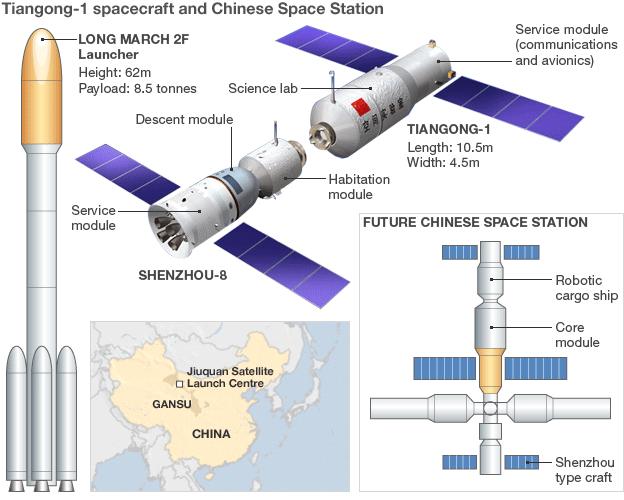

A rocket carrying China's first space laboratory, Tiangong-1, has launched from the north of the country.

The Long March vehicle lifted clear from the Jiuquan spaceport in the Gobi Desert at 21:16 local time (13:16 GMT).

The rocket's ascent took the lab out over the Pacific, and on a path to an orbit some 350km above the Earth.

The 10.5m-long, cylindrical module will be unmanned for the time being, but the country's astronauts, or yuhangyuans, are expected to visit it next year.

Tiangong means "heavenly palace" in Chinese.

The immediate plan is for the module to operate in an autonomous mode, monitored from the ground. Then, in a few weeks' time, China will launch another unmanned spacecraft, Shenzhou 8, and try to link the pair together.

This rendezvous and docking capability is a prerequisite if larger structures are ever to be assembled in orbit.

"Rendezvous and docking is a sophisticated technology," said Yang Hong, Tiangong-1's chief designer. "It's also essential to building China's own space station," he told the state broadcaster China Central Television.

China has promised to build this station at the end of the decade.

Assuming the Shenzhou 8 venture goes well, two manned missions (Shenzhou 9 and 10) should follow in 2012. The yuhangyuans - two or three at a time - are expected to live aboard the conjoined vehicles for up to two weeks.

Tiangong-1 was launched on the latest version of a Long March 2F rocket

The lab will go into a 350km-high orbit and will be unattended initially

An unmanned Shenzhou vehicle will later try to dock with Tiangong

The orbiting lab will test key technologies such as life-support systems

China's stated aim is to build a 60-tonne space station by about 2020

The Tiangong project is the second step in what Beijing authorities describe as a three-step strategy.

The first step was the development of the Shenzhou capsule system which has so far permitted six nationals to go into orbit since 2003; then the technologies needed for spacewalking and docking, now in progress; and finally construction of the space station.

At about 60 tonnes in mass, this future station would be considerably smaller than the 400-tonne international platform operated by the US, Russia, Europe, Canada and Japan, but its mere presence in the sky would nonetheless represent a remarkable achievement.

Concept drawings describe a core module weighing some 20-22 tonnes, flanked by two slightly smaller laboratory vessels.

Officials say it would be supplied by freighters in exactly the same way that robotic cargo ships keep the International Space Station (ISS) today stocked with fuel, food, water, air, and spare parts.

China is investing billions of dollars in its space programme. It has a strong space science effort under way, with two orbiting satellites having already been launched to the Moon. A third mission is expected to put a rover on the lunar surface. The Asian country is also deploying its own satellite-navigation system known as BeiDou, or Compass.

Bigger rockets are coming, too. The Long March 5 will be capable of putting more than 20 tonnes in a low-Earth orbit. This lifting muscle, again, will be necessary for the construction of a space station.

"There are loads of ideas floating around, and they're serious about implementing them," said UK space scientist John Zarnecki, who is a visiting professor at Beihang University, the new name for the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

"There's a sense of great optimism. It's not driven so much by science, but by the desire to develop new technologies. The money is there, although it's not limitless. And they're taking it step by step," he told BBC News.

Tiangong-1 has a two-year lifetime. It is likely to be followed by a second lab and possibly a third. China says that at the end of their missions, the modules will be driven into the atmosphere for a destructive descent into a remote part of the Pacific Ocean.

- Published29 September 2011

- Published29 September 2011

- Published25 August 2023

- Published29 June 2011

- Published1 October 2010