Nobel physics prize honours accelerating Universe find

- Published

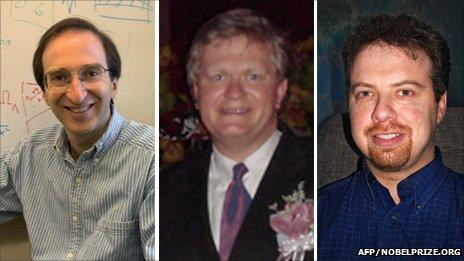

The three researchers' work has led to an expanding knowledge of our Universe

Three researchers behind the discovery that our Universe's expansion is accelerating have been awarded this year's Nobel prize for physics.

Saul Perlmutter and Adam Riess of the US and Brian Schmidt of Australia will divide the prize.

The trio studied what are called Type 1a supernovae, determining that more distant objects seem to move faster.

Their observations suggest that not only is the Universe expanding, its expansion is relentlessly speeding up.

Prof Perlmutter of the University of California, Berkeley, has been awarded half the 10m Swedish krona (£940,000) prize, with Prof Schmidt of the Australian National University and Prof Riess of Johns Hopkins University's Space Telescope Science Institute sharing the other half.

'Weak knees'

Prof Schmidt spoke to the Nobel commitee from Australia during the ceremony.

"It feels like when my children were born," he said.

"I feel weak at the knees, very excited and somewhat amazed by the situation. It's been a pretty exciting last half hour."

The trio's findings form the basis of our current understanding of the Universe's origins, but raises a number of difficult questions.

In order to explain the rising expansion, cosmologists have suggested the existence of what is known as dark energy. Although its properties and nature remain mysterious, the predominant theory holds that dark energy makes up some three-quarters of the Universe.

But at the time the work was first being considered, no such exotic explanations were yet needed.

"It seemed like my favourite kind of job - a wonderful chance to ask something absolutely fundamental: the fate of the Universe and whether the Universe was infinite or not," Prof Perlmutter told BBC News.

He led the Supernova Cosmology Project, external beginning in 1988, and Prof Schmidt and Prof Riess began work in 1994 on a similar project known as the High-z Supernova Search Team, external.

Their goal was to measure distant Type 1a supernovae - the brilliant ends of a particular kind of dense star known as a white dwarf.

Because their explosive ends are of roughly the same brightness, the amount of light observed from the supernovae on Earth should be an indication of their distance; slight shifts in their colour indicate how fast they are moving.

At the time, the competing teams expected to find that the more distant supernovae were slowing down, relative to those nearer - a decline of the expansion of the Universe that began with the Big Bang.

Instead, both teams found the same thing: distant supernovae were in fact speeding up, suggesting that the Universe is destined for an ever-increasing expansion.

Prof Perlmutter said the fact that the two teams were rivals was probably best to set the scene for a surprising outcome.

"It was fierce competition in those last four or five years of the work," he said.

"The two groups announced their results within just weeks of each other and they agreed so closely; that's one of the things that made it possible for the scientific community to accept the result so quickly."

That result in the end sparked a new epoch in cosmology, seeking to understand what is driving the expansion, and Prof Perlmutter is enthusiastic that such fundamental problems have been highlighted by the Nobel committee.

"It's an unusual opportunity, a chance for so many people to share in the excitement and the fun of the fact that we may be on to hints as to what the Universe is made out of. I guess the whole point of a prize like this is to be able to get that out into the community."

Commenting on the prize, Prof Sir Peter Knight, head of the UK's Institute of Physics, said: "The recipients of today's award are at the frontier of modern astrophysics and have triggered an enormous amount of research on dark energy."

"These researchers have opened our eyes to the true nature of our Universe," he added. "They are very well-deserved recipients."

The Nobel prizes have been given out annually since 1901, covering the fields of medicine, physics, chemistry, literature and peace.

Monday's award of the 2011 prize for physiology or medicine went to Bruce Beutler of the US, Jules Hoffmann from France and Ralph Steinman from Canada for their work on immunology.

This year's chemistry prize will be announced on Wednesday.

- Published3 October 2011

- Published19 May 2011