A billion pixels for a billion stars

- Published

- comments

The CCDs are arranged in rows across a support structure made of silicon carbide

I doubt those going to the Homebase DIY store in Chelmsford to buy a pot of paint give much thought to what goes on in the hi-tech factory building next door.

This is the HQ of e2v, external, a company that made its name producing valves for the post-war television industry but which now produces camera sensors for some of the biggest space missions flying today.

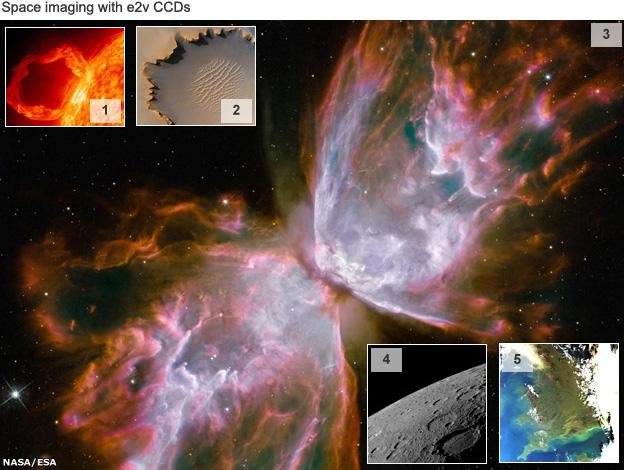

The latest pictures of Mars and Mercury, close-up movies of the Sun, and the extraordinary cosmic vistas from Hubble - all are acquired thanks to the charge-coupled devices (CCDs) manufactured at e2v in the East of England.

Simply put, CCDs turn the light falling on their surface into an electronic signal. For a camera system in, say, Hubble, which orbits some 560km above the Earth, that electronic signal is processed and transmitted to the ground where it can then be easily translated back into an image on a computer screen.

But whereas Hubble's premier instrument, the Wide Field Camera 3, incorporates just two e2v CCDs side by side, the sensor system the company has just completed includes 106 CCDs.

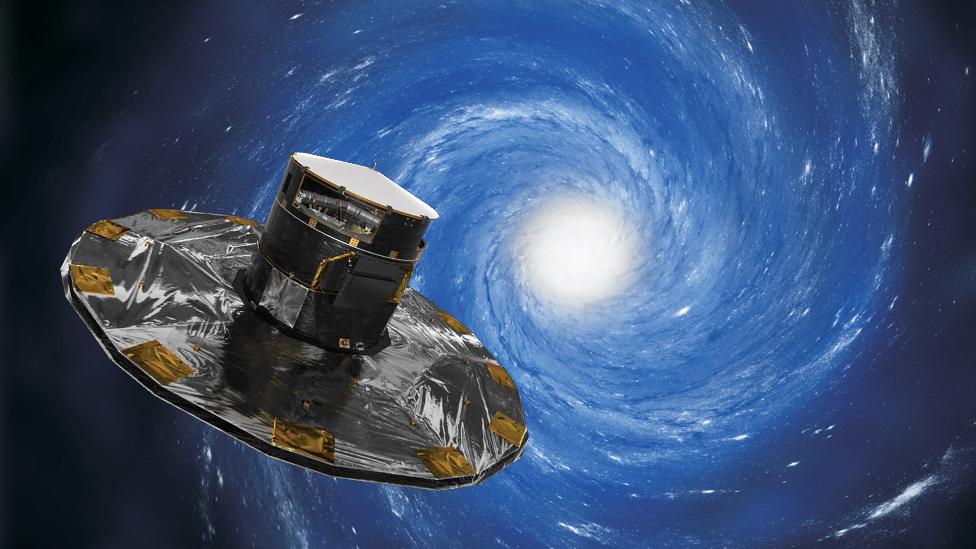

This huge (nearly one billion pixels) array will be fitted to the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite, external, due for launch in June 2013.

Gaia will be sent to an observing location 1.5 million km from Earth, from where it will slowly spin and scan the sky.

Over a five-year period, the satellite's e2v array, allied to two telescopes and some sophisticated instrumentation that includes an atomic clock, will make an unprecedented 3D map of our Milky Way Galaxy.

Gaia - The discovery machine

The Gaia mission will make a very precise 3D map of our Milky Way Galaxy

It is Europe's successor to the Hipparcos satellite which mapped some 100,000 stars

The one billion to be catalogued by Gaia is still only 1% of the Milky Way's total

But the quality of the new survey promises a raft of discoveries beyond just the stars themselves

Gaia will find new asteroids, failed stars, and allow tests of physical constants and theories

It will launch on a Soyuz rocket in 2013 and be stationed 1.5 million km from Earth

A supercomputer will be needed to prepare the final catalogue expected in about 2020-21

Gaia will detail the precise position, distance, movement, and composition of the brightest stars in the sky (out as far as the next galaxies such as Andromeda).

This information is expected to unlock new information about the structure, origin and evolution of our Galaxy. And because Gaia will track anything that passes across its e2v CCDs, it is likely also to see countless objects that have hitherto gone unrecorded - such as asteroids, planets beyond our Solar System, and tepid stars that never quite fired into life.

Its fine-scale measurements will even permit scientists to conduct some strenuous tests of General Relativity - Einstein's theory of gravity.

I know the label "discovery machine" is over-used by the media but for Gaia, it promises to be a case of "it does exactly what it says on the tin" (to borrow the advertising slogan they would recognise in the DIY store).

e2v got involved in the first feasibility work on Gaia in the late 1990s. Back then, the thought was for a huge satellite carrying two camera arrays incorporating some 500 CCDs.

"I think the key point that made it feasible was being able to compress the instrument down to just a single focal plane such that it would fit into a Soyuz [rocket] and wouldn't require an Ariane 5, and therefore could be done within the cost budget that Esa had in mind. Having done that, it looked like it might work - but it still looked pretty mad," recalls e2v's chief applications engineer, Dave Morris.

The company has worked solidly for more than five years to produce all Gaia's CCDs.

The light-sensitive area on each CCD detector measures 45.0mm by 59.0mm, encompassing 1,966 pixels by 4,500 pixels. The slim devices are arranged in rows across a support structure made of silicon carbide, a very light and very stiff material that will not bend or warp when it experiences the temperature extremes of space. Overall, the array covers just under half a square metre.

Picturing Earth and beyond

e2v provided CCDs for two of the three instruments flying on Nasa's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO)

Victoria Crater seen through the Chelmsford image sensors of the HiRise camera system on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO)

Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 was installed during the telescope's final servicing mission. It incorporates two e2v CCDs

e2v CCDs also went into orbit this year around the Planet Mercury with Nasa's Messenger spacecraft

Europe's Envisat spacecraft continues to provide pictures of the Earth nine years after launch

The idea is that Gaia's two telescopes will focus the stars on to the end of the array, and as these celestial objects then scan across the CCDs their positions and individual properties will be logged.

Although 106 were needed for the final mission, the associated development and test programme meant far more CCDs were actually delivered to satellite manufacturer Astrium, which is assembling Gaia in its facilities in Toulouse, France.

"The total number of flight models and flight spares was actually 130, which is really a significant number when you think that for most of our space programmes we're talking five or six flight devices, maybe 10," explained e2v principal project manager, Roy Steward. "And then of course there were engineering and other models along the way - 44 of those. So, 174 CCDs in total."

Gaia is certainly a long-term project. From first approval to launch will be 13 years. Gathering and processing all the data for its star catalogue will probably take another seven or eight years.

"The raw data that has to be collected is about 100 terabytes, and when all the data are processed in the archive we are talking about up to one petabyte," says Giuseppe Sarri, Esa's Gaia project manager. "For the analysis, a supercomputer will be needed to get out all the numbers."

To get all Gaia's information to the ground will require quite an impressive downlink capability: about 5 Mbit/s during its daily passes, similar to many home broadband connections today, but from 1.5 million km away.

e2v's Gaia project, valued all up at about 20 million euros, has been more than just an interesting challenge. The investments required at the Chelmsford site to produce all the CCDs - new cleanroom space and test equipment - mean that it is now in an excellent position to compete for more space business.

"Gaia forced the pace and pushed us ahead of the curve," says e2v marketing and applications manager, Jon Kemp.