Bringing gene therapy in from the cold

- Published

- comments

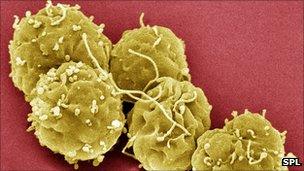

Stem cell therapy could become a viable alternative to surgery

Not so long ago gene therapy was the "Next Big Thing" in medical science. Revolutionary new treatments and cures, we were told, were just around the corner.

But when the 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger died during a clinical trial for a revolutionary new gene therapy technique in 1999, that bubble of expectation burst. The mantle of medical hyperbole - and the funding - moved on to other, as yet untarnished advances, including stem cells and the promise of personalised medicine.

Although investment in gene therapy withered, away from the limelight research has continued and in the intervening years a number of important breakthroughs and treatments have been developed. The latest of these, described in a paper published in the journal Nature, may go some way towards reinstating gene therapy in medical science's premier league.

Scientists at the Wellcome Trust's Sanger Institute and the University of Cambridge have succeeded in correcting the genetic mutation responsible for Antitrypsin deficiency - a debilitating condition that causes cirrhotic liver disease and lung emphysema in some 30,000 patients in the UK alone.

Starting with a skin biopsy from a patient suffering from the disease the team derived a population of iPS, or induced pluripotent stem cells, containing faulty copies of the alpha-1 antitrypsin gene.

Using molecular scissors they then removed the abnormal copies of the gene and replaced them with corrected versions, before stimulating the stem cells to differentiate into liver cells.

Finally they implanted these healthy liver cells into a mouse model - demonstrating not only that they functioned properly, but that over time, they re-populated the entire organ generating a disease-free liver.

Speaking on the programme this morning Cambridge University's Professor David Lomas hailed the result as a remarkable breakthrough.

"The genetic correction is really quite a phenomenal technical advance. Now we have to understand how we can safely use these cells in patients, because it's most important we don't do harm. The cells that we put back in have to be effective, have to function well, but most of all have to cause no harm to the patient."

It's early days, but if researchers can overcome the technical obstacles and safety concerns, the technique could offer patients a viable alternative to a liver transplant and a lifetime on immuno-suppressant drugs - and help bring gene therapy in from the cold.