Carbon: What price simplicity?

- Published

- comments

Taxing at source could help bring the Sun down on fossil fuel use faster than carbon trading

Is there a simpler way to put a price on carbon?

The biggest carbon trading project in the world - the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), external - has brought small declines in emissions across the bloc, but has few fans.

Opponents of climate regulation hate it because they see it as an expensive white elephant; proponents of tougher regulation hate it because EU member states have secured emission caps high enough that the carbon price (currently around 10 euros per tonne) remains below levels that could drive fundamental change.

Yet this is the model that other regions of the world - Australia, Japan, China, North America - are looking to replicate, and to link with.

The theoretical benefits of carbon trading are clear - reducing emissions as economically as possible, rewarding adaptable companies and punishing the dinosaurs.

But as things have turned out, it's possible to argue that the EU scheme has benefited few other than the growing army of traders who make percentages on all the deals.

It was only recently that Barclays Capital predicted , externalcarbon could become the world's biggest commodity market - which seems (to this mind) strange when it's a commodity that is not traded for its use, as are things like copper, cocoa and coal.

One alternative to ETS-style emissions trading that was much discussed a few years ago, personal carbon allowances, external, has many attractions in principle.

But it makes things more complex rather than less; and anyway, in the political atmosphere post-Copenhagen, external, the chances of introducing it have receded into the invisible part of the spectrum.

So, the question again: is there a simpler way to do it?

Julia Gillard's Australia is the latest to commit to carbon trading, following Jose Manuel Barroso's EU

Various figures have suggested at times over the last few years that the best approach would be to tackle carbon at source.

Simply, some kind of levy or tax or whatever would be imposed at the coal mine and at the oil and gas well.

As there are far fewer companies involved in these activities than might be candidates for emissions trading, the burden of administration should be much lower.

Yes, it would make fossil fuels and anything manufactured using them more expensive, as extractors would pass costs up the supply chain.

But ETS-style carbon trading makes things more expensive too; indeed, making fossil fuel use more expensive is the whole economic stick with which CO2 production is supposed to be beaten down.

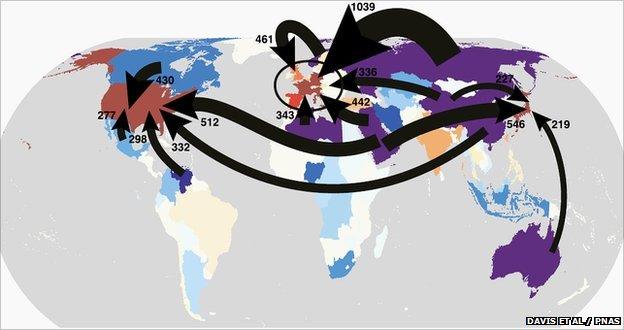

In the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) this week, external, a group of US-based scholars presents an analysis of the global flows of fossil fuels and carbon emissions that sets out the case for well-head pricing more clearly than before.

Some of its headline conclusions might not come as a surprise: Japan and Europe import most of their fossil fuels, the Middle East and Russia are major exporters, China and the US are both big users and fairly large importers.

When it comes to embedded emissions - CO2 produced during the manufacture of goods that are then shipped to another country - China is by far the biggest embedder of emissions, in goods that are principally destined for Western Europe and the US.

Interlinked world; the Stanford University researchers map carbon flow (fossil fuel trades and embedded carbon) around the world

By illustrating the sheer scale of these trades, the authors accomplish two things.

One is to show what some commentators view as the perversity of trying to regulate emissions on a country-by country basis, when some are generating those emissions by making goods that are to be used in a different country.

Which government should properly be responsible - the producer, or the consumer?

The second is to show how the politics of a carbon pricing based on well-head levies could be politically attractive to some of the countries that traditionally do most to stymie the UN climate negotiations.

The Gulf states, Russia, and Canada have all placed big political brakes on the UN process in recent years.

But they are also major fossil fuel exporters - and the authors of the PNAS paper cite other evidence showing how big exporters would gain economically from being the ones to implement the levy.

"Regulating the fossil fuels extracted in China, the United States, the Middle East (a region comprised of 13 countries in our analysis), Russia, Canada, Australia, India, and Norway would cover 67% of global CO2 emissions," they write.

It's not quite as simple as that, of course.

You might argue that citizens of the US or Japan or Germany could and perhaps should pay more for their fossil fuel use; but it's pretty tough if people in the poorest countries are penalised too for the little fuel they consume.

So you'd need opt-outs - and you'd also need ways to determine the size of any levy, and where and how the revenues it raises should be spent.

You'd also have to work out whether - and if so, how - to involve things like methane gathered from landfill sites, biofuels and black carbon.

There is another way in which the well-head levy could become politically attractive.

Remember that just before the Copenhagen summit nearly two years ago the rich nations of the world promised that by 2020 they will be funding poorer ones to the tune of $100bn per year?

Although there's been some progress on ways of raising the money, you'd be stretching reality to say there was a firm plan.

Could a levy on fossil fuel production globally that only feeds through to consumers in richer countries be the ticket?

Follow Richard on Twitter, external