Stricken Mars probe stays silent

- Published

The Phobos-Grunt mission had been eagerly awaited by scientists everywhere

Efforts are continuing to try to regain control of the Russian Mars mission that is stuck circling the Earth.

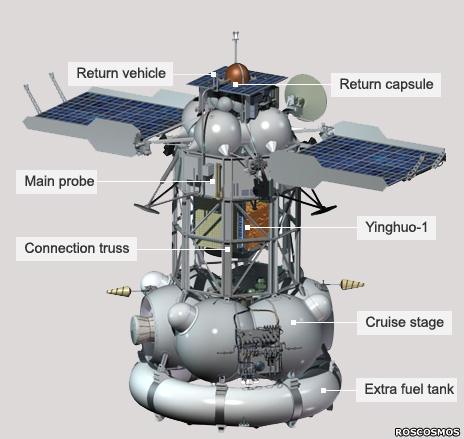

The Phobos-Grunt spacecraft was put in orbit on Wednesday, but failed to fire the engine that was designed to take it on to the Red Planet.

Engineers have been using tracking stations around the globe in an attempt to talk to the probe and diagnose its problems - but without success.

Europe has offered Russia its assistance.

The European Space Agency Spacecraft Operations Centre (Esoc) in Darmstadt, Germany, is now involved in trying to establish a link, using its antennas in French Guiana, the Canary Islands and on the Spanish mainland.

The US space agency (Nasa) has also offered to do anything that might bring the wayward craft under full control.

Doug McCuistion, Nasa's director of Mars exploration, told reporters in a briefing about its own forthcoming Red Planet venture, the Curiosity rover: "We have offered assistance and if they need it, we will provide it to the best of our ability."

Phobos-Grunt launched successfully on its Zenit rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and was dropped off into an elliptical orbit with an apogee (farthest point from Earth) of 345km.

It was then expected to initiate two firings on its big cruise stage, one to lift it higher in the sky and the second to despatch it to Mars. Neither burn occurred.

So far, the repeated passes of Phobos-Grunt over ground stations have failed to yield any telemetry.

The Russian Interfax news agency reported a space industry source on Friday as saying: "Several attempts have been made overnight to receive telemetry from the spacecraft. The result of all of them was nothing.

"The chance that the station could be saved is very, very slim," the translation from BBC Monitoring said.

"Russia's ground systems located at Baikonur and near Medvezhyi Ozera near Moscow will join in these efforts in the evening."

The community of citizen satellite trackers has, though, reported Phobos-Grunt to be in a stable orientation.

Michael Murphy from Dayton, Ohio, posted on Friday, external: "I just observed a pass of Phobos-Grunt and the Zenit second stage.

"The rocket body was tumbling slowly, and the probe itself appeared to be very steady as it passed.

"I did not get good timing information, but the probe was definitely steady. I saw no other objects along the track the probe followed," he told the Phobos-Grunt thread on the SeeSat-L website, external.

Fellow tracker Ted Molczan from Toronto, Canada, has been trying to determine the precise orbit of Phobos-Grunt around the Earth, and thought on Friday he had seen the craft rise slightly.

"This could all still turn out to be due in some way to spurious [data], but I suspect the effect is real," he told the same thread, external. "If venting is occurring, perhaps due to leakage from the propellant system, then the spacecraft could eventually begin to tumble."

If control of Phobos-Grunt cannot be re-established, the focus of interest will very rapidly shift to the spacecraft's certain fall to Earth.

Residual air molecules more than 200km above the planet will generate drag on the probe and pull it down faster and faster - although it could be some weeks yet before there is an impact.

The spacecraft weighed some 13 tonnes at launch - double the mass of Nasa's recently re-entered UARS satellite.

What is more, most of the 13 tonnes is made up by the propellants unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and dinitrogen tetroxide (DTO), both of which are toxic.

It was the presence of a large quantity of toxic propellants on the returning spy satellite USA-193 that the American government used to justify its decision to shoot down the spacecraft with a missile in 2008.

Landing site

If the Phobos-Grunt mission is truly lost, then professional and amateur groups will be modelling the decay in its orbit in an attempt to determine precisely where and when it might come down.

As with UARS, much of the spacecraft will burn up in the atmosphere; but any parts made of high-temperature metals, such as titanium or stainless steel, stand a chance of making all the way to the surface.

Indeed, it is the fuel tanks that often survive the fall, their spherical shapes enabling them to spin up and dissipate heat more easily.

However, the probability is that any debris would hit the ocean, given that more than 70% of the Earth's surface is covered by water. This was the case with UARS and the German Rosat X-Ray telescope that returned to Earth last month.

But no-one wants to see Phobos-Grunt end this way. This exciting mission had been eagerly awaited by scientists all over the world.

Its quest is to land on the Martian moon Phobos and scoop up rock for return to Earth. Such a venture could yield fascinating new insights into the origin of the 27km-wide moon and the planet it circles.

The mission is also notable because it carries China's first Mars satellite, Yinghuo-1.

- Published9 November 2011

- Published26 October 2011

- Published28 September 2011

- Published4 November 2011

- Published19 July 2011

- Published21 September 2010