Weather satellites and the gathering storm

- Published

- comments

By common consent, Metop has been a revelation since its launch in 2006

Nothing illustrates better the benefits to society of space activity than meteorological satellites. Weather forecasts save lives and limit damage to property.

We've seen forecast skill steadily improve over time, and much of that can be put down to the information now coming from orbiting sensors.

In Europe, the backbone of this data stream is provided by Metosats 8 and 9, external which sit high above Africa and relay pictures of the developing systems coming our way.

But one of the big innovations of recent years has been the low-orbiting satellite. Again, in Europe, this is called Metop, and this four-tonne platform circles the globe, pole to pole, every 100 minutes.

It delivers high-resolution information on the state of the atmosphere that supplements the broader imagery coming from the geostationary Meteosats and the point measurements we get from balloons (radiosondes), and the like.

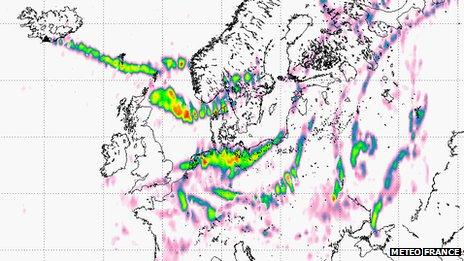

Metop's suite of instruments retrieve a range of data - from the temperature and water content of the different layers in the atmosphere to the speed of the winds whipping across the ocean, and from the health of the ozone layer to the spread of volcanic ash plumes across the sky. It even has a role in search and rescue.

By common consent, Metop has been a revelation since its launch in 2006, external, and we exchange its data with the Americans who run a similar operation, giving us double the value.

Metop tracked the ash plume from the Eyjafjallajokull volcano in Iceland

If you weight the importance of the various data components that now underpin the 24-hour forecast, then Metop is probably responsible for some 25% of the impact. It's that important. And there've been big gains also in medium range forecasts - those that go out to 3-7 days ahead.

I've written recently about the mess the Americans seem to have got themselves into with their counterparts to Metop - the Noaa series of satellites.

The US has just put up its latest spacecraft, called NPP, which will soon be feeding data into our forecasts. But many commentators expect its instruments to start to fail in the harsh space environment several years before its successor, a satellite called JPSS-1, can be launched to take over observation duties.

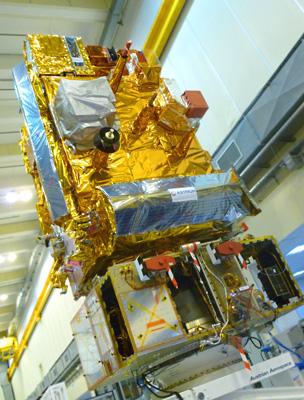

Metop-B will launch in May/June next year

It is almost certain there'll be a gap in the acquisition of civilian US polar satellite meteorological data at the end of this decade.

Europe is very keen not to get itself into a similar situation. Fortunately, it has two spare Metop-class spacecraft already built, and can stagger their launch to ensure there is continuity of data through to at least 2020. The first of these spares - appropriately called Metop-B - is in final preparation for a lift-off in May/June next year, external. Europe cannot relax, however. Because of the time it takes to develop and build these special satellites, it's imperative we start planning a follow-on series today. And that is precisely what is happening. The project has the rather ungainly codename at the moment of EPS-SG - but its technology promises to be cutting-edge.

Instead of one satellite carrying every instrument, EPS-SG is likely to split the complement across two separate platforms. The probable cost of this project? Something just shy of 3bn euros.

It will be a joint venture between the European Space Agency (Esa), external and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (Eumetsat), external. Simply put, Esa will do the R&D and Eumetsat will operate the satellites, as it does with Metop now.

The two organisations will also share the cost of the project. Esa member states will put in a third; Eumetsat member states will put in two-thirds.

This is the moment when the palms of British industry start to sweat slightly. I promised you I'd write about the big decisions coming up that will affect the UK space sector and they don't come much bigger than EPS-SG. Britain played a significant role in the development of Metop, external, building the service structure and propulsion modules for all three spacecraft, as well as providing MHS (Microwave Humidity Sounder, external) - an instrument that retrieves important information about humidity in the atmosphere - for Metop and its American counterparts.

UK industry is anxious to play its part again but it still has nightmares about what happened the last time a big meteorological satellite contract came up in Europe. On that occasion, the proposal on the table was to upgrade the Meteosats, external - a project costing slightly more than 3bn euros. The then British government (2008) took the view that it was getting the data anyway through its membership of Eumetsat and walked away from investing any money in the Esa R&D effort, external. The result? British industry was locked out of contracts worth many tens of millions of euros even though also as a Eumetsat member, the UK was still obliged to put hundreds of millions euros into the project. In effect, Britain ended up subsiding hi-tech jobs in France and Germany.

The UK also built the Metop service module - the part that manages the satellite in orbit

The R&D part of EPS-SG will be presented to the next big meeting of European space ministers for approval next year. It will be priced about 750m euros. Those nations that choose to invest in the first pair of satellites and their instruments will also get to build the follow on pairs. Once again, France and Germany are already reaching for the cheque book, promising to provide instruments from their national programmes.

UK industry and academia have formed a coalition for EPS-SG, to lobby the current government to ensure there is no repeat of the Meteosat story.

Britain will be obliged to pay something approaching 300m euros for EPS-SG anyway as a member of Eumetsat, where it will be a mandatory programme, external. But if the UK wants a sizeable chunk of the industrial work, it must commit to the Esa R&D, which will be an optional programme (a GNI weighted contribution would be on the order of 100m euros).

Justin Byrne, deputy director of Earth Observation, Navigation and Science at Astrium UK, which led the British participation last time, told me: "The way these programmes work is that unless you invest in the Esa side, you're out. And from the perspective of our European cousins, they see these programmes as a marvellous way to leverage the money they put into the Eumetsat budget back to their country.

"The next generation of MHS is called MWS. It will do a similar job to MHS, which is to look at the water content in the atmosphere, but it will be far more performant - it's got extra frequency bands. We've got all the scientists behind us, and Esa, who would love us to provide this instrument because we have the capability and the credibility to do it - and the Americans feel the same way. But because of the lack of commitment shown by the UK over the next generation of Meteosat, we've got the Italians and the Spanish lining themselves up to take the instrument away from us."

The UK Space Agency tells me that it is working closely with the UK Met Office, and that a coherent case is being presented to ministers. However, as with the European Lunar Lander project I wrote about in my last posting, EPS-SG is having to compete for funds alongside a wide range of very worthy projects.