Climate deal pushed by poorest nations

- Published

Some of the LDCs are at risk of inundation if sea levels rise as forecast

The world's poorest countries have asked that talks on a new climate deal covering all nations begin immediately.

At the UN climate summit, the Least Developed Countries bloc and small island states tabled papers saying the deal should be finalised within a year.

Many of them are vulnerable to climate impacts such as drought or inundation.

The move puts the blocs on a collision course not only with many rich nations, but also with developing world partners such as China, India and Brazil.

These three developing world giants believe talks on a new mandate should not begin now because developed nations have yet to fulfil existing commitments.

But their smaller peers believe there is no time to lose.

"We put forward our mandate for a new legal agreement today to get things moving quickly in an effort to respond to the urgency of our challenge," said Selwin Hart, lead negotiator for Barbados, speaking for the Alliance of Small Island States (Aosis).

"We can no longer afford to wait. We need to conclude the new deal in the next 12 months."

The move was backed by EU Climate Commissioner Connie Hedegaard.

"Good news from Durban," she said.

"The LDCs and Aosis are thinking along the same lines as the EU on the roadmap. The world doesn't need more time to reflect, it needs decisions.''

Water woes

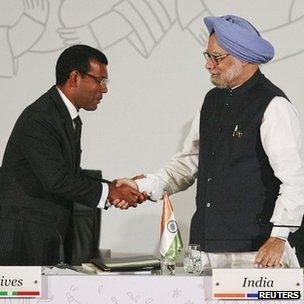

India and The Maldives have a common agenda on many things - but maybe not on climate

The 48-country Least Developed Countries bloc (LDCs) includes drought-prone states such as Ethiopia and Mali, those with long flat coastal zones such as Bangladesh and Tanzania, and Himalayan mountain states including Bhutan and Nepal for whom melting glaciers pose serious dangers.

The 39-strong Aosis includes a plethora of Pacific and Caribbean islands, some of which are very low-lying and vulnerable to sea level rise.

The draft mandate that the LDCs launched into the current UN summit in Durban, South Africa, says that talks "shall begin immediately after 1 January 2012 and shall conclude... by COP18 (next year's summit)".

"All Parties must take urgent action to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and set a long term goal so as to hold the increase in global average temperature below 1.5C above pre-industrial levels and stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere below 350 parts per million of carbon dioxide equivalent (350ppm CO2e)," it continues.

The 1.5C goal is tougher than the 2C goal originally tabled by the European Union and subsequently adopted at last year's UN conference in Mexico.

But 1.5C is supported by more than half of the world's governments, including members of the LDCs and Aosis.

However, stabilising at 350ppm CO2e is a very demanding target, given that the current concentration is about 435-450ppm.

The LDC draft mandate continues: "The negotiations shall also be guided by the fact that in order to achieve the long term goal, global emissions should peak by no later than 2015 and will need to be reduced by at least 85% below 1990 levels by 2050."

Measures stemming from the new mandate should "operate alongside" emission cuts made under the Kyoto Protocol.

The Aosis draft is much shorter but makes the same essential point - that negotiators should "develop and finalise a Protocol or other legally binding and ratifiable instrument(s) under the Convention to be presented for adoption by the COP at its 18th session".

Degrees of separation

Brazil and India have argued that no new process should begin before 2015; and China is also known to be resistant.

Along with Canada, the US, Japan and Russia, they have also argued that the current pledges on curbing emissions, which most countries tabled around the time of the Copenhagen summit two years ago and which run until 2020, should not be adjusted before that date.

But the UNFCCC is obliged to review those pledges in 2015; and the LDCs believe the 1.5C target will be very difficult if not impossible to achieve without strengthening the existing pledges.

In the past, the developing world has resisted endorsing a global target for emissions in 2050, as it implies that developing countries will have to accept binding cuts.

The LDCs and Aosis are used to finding themselves in the opposite corner to the US and other developed nations.

But going up against the might of fellow developing countries is a relatively new experience, and has been taken only because they did not see their interests as compatible with the waiting strategy of India, Brazil and China.

"Delaying a new agreement or deeper targets until 2020, as some of the big emitters have proposed, is not an option," Mr Hart told BBC News.

"It is quite frankly a dereliction of our collective responsibility to present and future generations."

The proposals are likely to gain support from the EU and some Latin American nations.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

- Published28 November 2011

- Published28 November 2011

- Published23 November 2011

- Published21 October 2011