Have scientists at the LHC found the Higgs or not?

- Published

Supersymmetry predicts the existence of mysterious super particles.

<bold>The discovery of the Higgs Boson would undoubtedly be the biggest scientific breakthrough of the century so far. </bold>

Arguably, it would be the most important discovery since Crick and Watson worked out the structure of DNA nearly 60 years ago. On Tuesday, researchers at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) will say how close they are when they present the results from two of the experiments searching for the Higgs.

One thing is for sure, the researchers won't have all the data they need to make a definitive statement that they have discovered the sub-atomic particle. But in the best-case scenario they may come very close.

Indeed, they may privately feel "in their bones" that they have found it but be unable to call it a discovery publicly.

The Higgs is a sub-atomic particle responsible for giving all other particles their mass. It is therefore crucial to our understanding of the Universe.

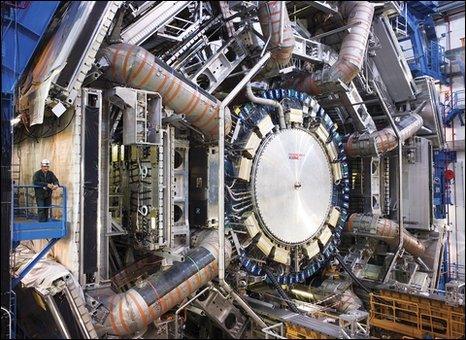

There are two experiments, or "detectors", searching for the Higgs in completely separate ways: the Atlas and the CMS collaborations. Each is looking for a signal of its presence among the billions of collisions that are occurring in each detector. In graphical form it would look like a little spike in the data.

<bold>Jump for joy</bold>

At this stage, any spike they may see could be a statistical anomaly and disappear in time as more data is gathered in the next run of collisions which starts in the new year. That is why no one will want to say they have discovered the Higgs at this stage, even if they do find an enticing spike on their graphs.

By early March, they will have enough data to know for sure whether the Higgs exists or not, and that is when the discovery or non-discovery will be official.

But there is a big "but". If on Tuesday both experiments find a big spike, each of them in exactly the same place and in the place that they expected to find the Higgs, the temptation for even the most dispassionate physicist to jump for joy will be irresistible.

In this scenario, Prof Rolf Heuer, the head of Cern (the organisation that runs the LHC), will still be duty-bound to say that this is not a definitive discovery.

It cost billions of pounds to build - what if it doesn't find the Higgs?

He is likely to say that we may have very strong hints of the Higgs, and that he hopes these will be confirmed in 2012. But Prof Heuer and his colleagues cannot make any stronger public statement, just in case those peaks become smaller as the next run of collisions begins.

But there are two other scenarios.

It is possible that neither experiment has detected any signal across the range where the Higgs is expected to be found. This too is incredibly interesting; far more interesting to physicists than finding the Higgs, in fact.

This would again provide a very, very strong indication that the Higgs as predicted by the current so-called Standard Model of physics does not exist.

Again, LHC scientists would not be able to rule it out for sure - but in their hearts they will know that in a few months' time they will have made a discovery that will have consigned a very important part of our current theory of particle physics to the dustbin.

<bold>Exciting times</bold>

In this case too, Prof Heuer and colleagues will quite rightly be cart-wheeling in the privacy of their offices.

The third and most ambiguous outcome is if the results from each experiment are substantially different, in which case we'll have to wait until March to know whether the Higgs exists or not.

The significance of discovering the Higgs cannot be overstated. Once physicists know it exists, they can begin studying it detail and finding out whether there are many different types of Higgs. Most importantly, theoretical physicists can discard various alternatives to the Standard Model and kick on, trying to develop it further.

As successful as the Standard Model has been, it still doesn't encompass gravity. Nor does it provide a reason for why there was an excess of matter over anti-matter after the Big Bang, allowing the Universe to come into being. And the theory accounts for the behaviour of just 4% of the Universe - its normal matter. The rest, in the form of dark matter and dark energy, remains to be explained.

However, if the Higgs is ruled out, life does get very interesting indeed. It means that the keystone which keeps the Standard Model propped up doesn't exist, paving the way for new, more exotic theories.

Whatever happens on Tuesday, the discovery or non-discovery of the Higgs boson will mark the end of only the beginning of a new chapter in physics.

Just as our understanding of the Universe and our place in it was transformed by learning about the structure of the atom and Albert Einstein's equations of space-time, the discoveries over the next 50 years will, I suspect, be even more important and awe-inspiring.

Follow Pallab <link> <caption>on Twitter</caption> <url href="http://twitter.com/#!/@bbcpallab" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published13 December 2011

- Published4 July 2012