Tracing the origins of a 'yeti's finger'

- Published

An anatomical specimen labelled "Yeti's finger" has been left overlooked in a museum for decades, its origins unexplained, until BBC reporter Matthew Hill set out to investigate.

In the vaults of the Royal College of Surgeons' Hunterian Museum in London are thousands of anatomical specimens from both human and animal species.

Still used as a teaching museum today, it was founded in the 18th Century by John Hunter, a surgeon, anatomist and naturalist.

His collection has been added to over the years, including in 1975 when a collection of research specimens and notes were bequeathed to the museum by primatologist Professor William Osman Hill.

The collection's catalogue was only rudimentary, and many specimens had not been cleaned or prepared, meaning there was little interest in terms of research, and much of it was left unseen for many years.

But in 2008, work on Prof Hill's collection turned up something very odd: a box of items apparently relating to his interest in crypto-zoology, the study of animals not proved to exist.

It contained plaster casts of a footprint, hair, scat (dropping) samples and an item recorded as a yeti's finger.

The specimen was 9cm (3.5 inches) long, 2cm wide at the widest part, curled and black at the end with a long nail.

According to the notes in the box, it was taken from the hand of a yeti. Its origin was listed as Pangboche Temple in Nepal.

Yeti expedition

Professor Hill's notes recorded that the finger had been brought to him by Peter Byrne, a former explorer and mountaineer.

Mr Byrne is now 85, and living in the United States, I discovered. When he recently visited London, I arranged to meet him.

He did indeed bring the yeti's finger to London, he explained. His story began in 1958, when he was a member of an expedition sent to the Himalayas, to look for evidence of the legendary Abominable Snowman.

"We found ourselves one day camped at a temple called Pangboche," Mr Byrne told me.

"The temple had a number of Sherpa custodians. I heard one of them speaking Nepalese, which I speak.

"He told me that they had in the temple the hand of a yeti which had been there for many years.

"It looked like a large human hand. It was covered with crusted black, broken skin.

"It was very oily from the candles and the oil lamps in the temple. The fingers were hooked and curled."

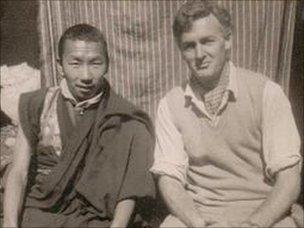

Peter Byrne was photographed in Tibet in 1958/9

Returning to London, Mr Byrne found himself repeating the story to Prof Hill in a restaurant at Regent's Park Zoo, a meeting set up by the expedition's American sponsor, Tom Slick.

"Osmond Hill said: 'You have got to get this hand. We've got to see it. We want to examine it.' But I had already asked the lamas there if I could have the hand and they said no, it would bring bad luck, disaster to the temple if it was taken away."

Prof Hill and Mr Slick asked Mr Byrne to go back and at least try to get one finger with permission from the temple's custodians.

The plan was to replace the missing finger with a human finger. Prof Hill then brought out a brown paper bag and tipped out a human hand onto the table.

"It was several months old and dried. I never asked him where he got it from."

Returning to the temple, he gave a donation in return for the finger, and then wired the human finger onto the relic.

Mr Slick helped ensure the finger would reach London safely with the help of his friend, the Hollywood actor James Stewart and his wife Gloria, who were in India at the time.

They were to meet in the Grand Hotel in Calcutta, said Mr Byrne.

"They were a little bit worried about customs, so Gloria hid it in her lingerie case and they got out of India no trouble.

"They arrived at Heathrow, but the lingerie case was missing."

A few days later, a customs official returned the case to the Hollywood couple, reassuring Gloria that a British customs officer would "never open a lady's lingerie case".

The finger was handed over to Prof Hill after which, Mr Byrne explained, he lost contact with him.

DNA test

But could this finger really have come from a yeti?

The Royal College of Surgeons granted a request for a DNA test to be carried out on a tiny sliver of the finger.

The finger is of human origin, according to Dr Rob Jones, senior scientist at the Zoological Society of Scotland.

"We have got a very, very strong match to a number of existing reference sequences on human DNA databases.

"It's very similar to existing human sequences from China and that region of Asia but we don't have enough resolution to be confident of a racial identification."

Primatologist Ian Redmond examines an anatomical specimen labelled 'Yeti's finger'

The "yeti's finger" is now all that remains of the original yeti's hand, which was stolen from Pangboche monastery in the 1990s.

Mike Allsop, a New Zealand pilot and mountaineer, became aware of the story and was moved to help the monastery get the hand back.

He has recently launched a campaign to find the original hand and has also made a replica, which he recently presented to the monks.

He informed me the monastery would like to have the finger returned, but does not want any trouble. I understand the Royal College of Surgeons is keen to help.

Matthew Hill presents Yeti's Finger on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 27 December 2011 at 11:00 GMT. Or catch up online afterwards at the above link.