Alien hunters: What if ET ever phones our home?

- Published

For decades we've been sending signals - both deliberate and accidental - into space, and listening out for alien civilisations' broadcasts. But what is the plan if one day we were to hear something?

If we ever detect signs of intelligent alien life, the people likely to be on the receiving end of a cosmic signal are the scientists of Seti, aka Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence.

This loose band of a couple of dozen researchers around the world doggedly listens to the cosmos in the hope of catching alien communications. It's often in the face of scant funding and even ridicule.

They watch signals coming from the world's largest radio telescopes, looking for anything unusual, or even the flashes of laser "lighthouses" designed to catch our attention.

Seti started as one man using one telescope dish in 1959. Today computers are used to sift through the cosmic radio traffic, flagging up to astronomers any potential calls from extraterrestrial life.

But what might happen if one of those computers found a bona fide alien phone call?

Conspiracy theorists will argue there would be a government cover-up. Even more nervous types might say there would be global upheaval.

The BBC's Jason Palmer and Matt Danzico visited Northern California's Allen Telescope Array

Seth Shostak, the Seti Institute's principal astronomer, says both groups should calm down.

"The idea that governments would keep this quiet because otherwise the public would go nuts, is nuts. History shows that's not what happens.

"In the early 1900s, there were claims that there were canals on Mars - a vast hydraulic civilisation just 50m km from Earth. The average guy in the street said 'well, I guess there are Martians' - they didn't panic."

The first job if the computers flag up an interesting signal is to get it confirmed by other telescopes around the world - this would take the better part of a week.

"In all that time, you can be sure people are emailing boyfriends and girlfriends, writing on their blogs... the word will be out there."

So news of alien contact may reach most people via a tweet from a Seti astronomer.

A 1997 "false alarm" signal showed the likely reaction - and the futility of any cover-up attempts.

"We were watching this signal all day and all night, waiting for somebody from 'officialdom', whatever officialdom is, to call up," Dr Shostak recalls. "Even local politicians didn't call up, let alone the federal government. The only people that were interested were the media."

Surely there's an action plan in a red binder somewhere, detailing which international bodies to inform?

Not so. "The protocol is simply to announce it," Dr Shostak says. And then the policies for a chain of information, or command over the situation? "There are no such policies, and I don't think you could enforce them anyway."

The United Nations has a small outfit in Vienna called the Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), and Seti scientists have tried down the years with little success to work with it to fill that notional red binder with plans. Asked what might happen if an alien message arrives, UNOOSA replies that their current mandate "does not include any issues regarding the question you pose".

So planning is left to people such as Paul Davies of the Beyond Center at Arizona State University, who heads up the the Seti Post-detection Taskgroup. But we don't know what kind of information - if any - an incoming signal might contain. And decoding the signal could take years, or decades.

But what might it say? It could just be a beacon, saying nothing more than "Hello, Earthlings, we are here," says Prof Davies.

"It could be something completely disruptive and transformative, something as simple as how to gain control over the nuclear fusion process... which could solve the world's energy crisis.

"Because of the enormous travel time from some source many, many light years away, we have plenty of time to reflect on what the consequences would be if we open up a dialogue on this slow time scale."

Ask anyone in the Seti community if we should reply, and the consensus is yes. But what to say, and how to say it is a thorny problem.

"When we're dealing with an alien mind - what they might appreciate, what they might regard as interesting or beautiful or ugly - will be so much tied to their neural architecture that we really couldn't guess," Davies says. "So the only thing that we've got in common has got to be at a mathematics and physics level."

Back in California's Seti Institute, director of interstellar message composition Doug Vakoch agrees.

"It seems a little hard to understand how you'd build a radio transmitter if you don't know that two plus two equals four.

"But how do we build upon that common understanding to communicate something that is more idiosyncratic to each species? How do we let them know what it's really like to be human?"

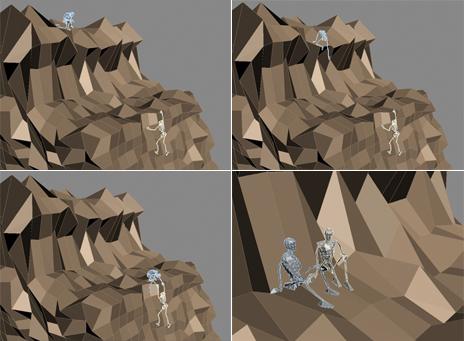

One possible reply could be animations showing human characteristics - Doug Vakoch prepared this to explain altruism

Some Seti scientists argue that, once we know where to send an interstellar email, we might as well just send the contents of the entire internet, streamed down a laser light beam. Aliens would then have plenty of information from which to draw patterns, disentangle languages, and see images - of all kinds - of what it is to be human.

Vakoch thinks to send such a "digital data dump" is an "ugly" approach. "There has to be something more elegant to say about ourselves than that."

We could instead express our idea of beauty - albeit crudely - by sending a signal representing the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the prior two: one, one, two, three, five, eight, 13 and so on. It's a sequence seen in spiral galaxies and the way nautilus shells grow, and is tied to the "golden ratio" - an aesthetically pleasing proportion seen in classical architecture.

The mathematical beauty of a nautilus shell

Dr Vakoch also hopes to show possibly idiosyncratic human characteristics, such as altruism, helping others at a cost to ourselves. To that end, he has prepared a simple animation of a person helping another up a cliff.

But any eventual message will be put together by international consensus - which will only be on the negotiating table if a signal actually shows up. In the meantime, he will keep coming up with ideas of what to say on the interstellar microphone.

"Perhaps more important than even communicating with extraterrestrials, this whole enterprise of composing messages is a chance to reflect on ourselves and what we care about and how we express what's important."

Part two of Seti: Past, Present and Future will be broadcast at 19:32 GMT on BBC World Service, Monday 16 January and the podcast can be found here. The first part can be found here.

- Published9 January 2012

- Published23 August 2010