Video tracks stricken Mars probe

- Published

- comments

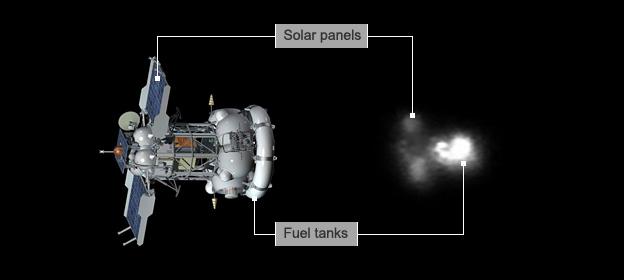

Thierry Legault's video of the Phobos-Grunt probe

The failed Russian Mars probe Phobos-Grunt has been pictured moving across the sky by the Paris-based amateur astronomer Thierry Legault.

The spacecraft is seen moving left to right in the video. The bulbous shape of its fuel tanks and its outstretched solar panels are easily discernable.

Mr Legault uses a sophisticated telescopic tracking system and captured similar imagery of Nasa's defunct UARS satellite last year.

Phobos-Grunt is falling to Earth.

It is expected to re-enter the atmosphere in the next 8-9 days and burn up.

The Russian space agency (Roscosmos) said on Friday that perhaps 20-30 pieces weighing no more than 200kg, external in total might survive the destructive dive and impact the surface somewhere.

Asked how easy it was to grab the shots with his telescopic system, Thierry told BBC News the, "difficulty was very comparable to UARS; they had comparable speed, brightness and size. Except that I had to drive more than 800km to find clear skies in the French Riviera!"

Thierry with his equipment at the Calern Plateau Observatory above Nice

The engineer has posted the video and how he went about acquiring it on his Astrophotography website, external.

On Friday, Phobos-Grunt was moving around the Earth at an altitude that varied between 177km (perigee) and 224km (apogee), external. But this orbit will rapidly decay over the coming week as the spacecraft drags through the top of the atmosphere.

As it encounters more and more air, so its descent will accelerate.

The spacecraft's mass at launch was just over 13 tonnes, but some 10 tonnes of this was the fuel it expected to use in the course of its mission to the Red Planet's largest moon.

The propellants, unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and dinitrogen tetroxide (DTO), are highly toxic but they will almost certainly be consumed in the fireball that engulfs Phobos-Grunt when it makes its death dive to Earth.

Part of the confidence on this matter stems from the construction of the fuel tanks.

"The Russian space agency reports they are largely made of aluminium, which has a very low melting temperature, compared to the titanium tanks that can survive re-entry and can sometimes be found on the ground," explained Dr Holger Krag from the European Space Agency's Operations Centre (Esoc), external in Darmstadt, Germany.

"We can expect the tanks to break up and release their contents. There will be a self-ignition of the UDMH and if it does not all burn up, it will be so dispersed there will not be a critical concentration."

Dr Krag and colleagues at Esoc, like a number of teams around the world, are now busy modelling the decay in Phobo-Grunt's orbit.

Esa is a member of the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), external, a forum for the worldwide coordination of activities related to the issues of man-made and natural debris in space.

The other teams working through the IADC will all be using slightly different assumptions in their models and, as a consequence, will all arrive at slightly different timings for the period of impact. A host of amateur groups will be engaged in a similar endeavour.

The hope is that by comparing the different pre-fall projections with the observed re-entry data after the event, future modelling efforts can be finessed.

At the moment, the projections are very uncertain. They are clustering around Sunday 15 January (GMT) and Monday 16.

Much of the uncertainty is related to the state of the atmosphere. During phases of higher solar activity, the atmosphere becomes excited and more extensive, pulling spacecraft and other pieces of debris in towards the Earth much faster than during phases of low solar activity.

Right now, the Sun is moving towards what is expected to be solar maximum - its most active state - over the next year or so, meaning that we are entering "harvest time" for space junk.

But precisely where Phobos-Grunt will re-enter in the coming days is really anyone's guess at the moment.

The maximum latitudes seen by its orbit are 51.4 degrees North and South. This encompasses London (UK) in the Northern Hemisphere and Punta Arenas (Chile) in the Southern Hemisphere.

"But remember, the prediction uncertainties currently are on the order of one or two or even three days and Phobos-Grunt is making one full revolution of the Earth every 90 minutes - about 16 orbits a day. So, it's just not possible to identify a particular region at the moment," Dr Krag told BBC News.

What would help would be a wider ground network of radar sensors to scan the sky.

The more frequently a spacecraft's orbit is sampled, the better the projections would get, particularly towards those final hours before impact.

Esa is building up its Space Situational Awareness programme, external, and the other agencies involved in the IADC are doing likewise.

"If we ever got the system we dream of, with a really good, globally distributed system of sensors, then we might be able to do a last prediction one or two hours before the actual re-entry," Dr Krag speculated.

"You might be able to nail it down to regions, oceans or continents - perhaps selected countries, but not any further in my view."

If Phobos-Grunt comes back in over a part of the world that is in darkness, it should produce a plasma trail that is visible to anyone watching from land or on a ship.

Europe saw a spectacular example of this on the night of 24 December, external when a Soyuz rocket stage fell to Earth.