Bubble-blowing stars seen in the thousands by public

- Published

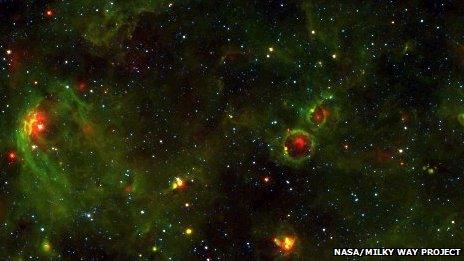

Members of the public are asked to spot "bubbles" in striking infrared images

A project to spot the "bubbles" that young, massive stars blow in the gas surrounding them has come up trumps, finding more than 5,000 of the objects.

That increases the known catalogue of bubbles by more than a factor of 10.

The discoveries were made by citizen scientists studying images from the Spitzer space telescope, as part of theMilky Way Project, external.

The much-improved catalogue, externalwill be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

One of the great remaining mysteries of how our Universe works is how stars themselves form in vast clouds of swirling gas.

Astronomers are keen to find star-forming regions, hoping to catch the process at various stages to better understand it.

Groups of stars form in clusters near particularly large stars, and one good hint of these stellar nurseries is the "bubble" that they blow into the surrounding gas - a bubble that can be seen in pictures taken by Spitzer's infrared camera.

Human intervention

But the task to find and list all the bubbles in existing high-resolution images taken by Spitzer is a daunting one.

The largest previous cataloguing effort was carried out in 2007 by a handful of US astronomers poring through the images with their own eyes;it came up with 269 bubbles, external.

Automating the process with a computer algorithm is not an option, said Eli Bressert of the European Southern Observatory and Milky Way Project team member.

"To have an algorithm that can identify that kind of structure, no one can do it a the moment - it's way too complex," he told BBC News.

"You need two things: pattern recognition and the ability to judge, based on the other data that you've seen, what's good and what's bad - and that's what humans are good at."

Enter the Milky Way Project, which grew from the riotously successful citizen science project to classify and describe types of galaxies,Galaxy Zoo, external.

The new project invites the public to take part by sifting through images from the huge archive of data provided by Spitzer'sGlimpse, externalandMipsgal, externalsurveys.

The task is simply to look for bubbles in the pictures and mark them. The same images are presented to a number of participants, making use of the "wisdom of crowds" to shore up the certainty of each bubble identification.

Nearly a half a million images have been sifted through by about 35,000 volunteers, with about a million different individual identifications made.

The result reported in the new paper: 5,106 bubbles - suggesting that our galaxy, as Mr Bressert put it, "is basically like champagne, there are so many bubbles".

The data represent a valuable road map for star-forming regions in the galaxy, but they also show an inexplicable trend: a dearth of bubbles just on either side of the galactic centre.

That is just one of the research directions that will come out of the project, Mr Bressert said.

"We thought we were going to be able to answer a lot of questions, but it's going to be bringing us way more questions than answers right now.

"This is really starting something new in astronomy that we haven't been able to do."