Bloodhound diary: Feel the force

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h).

Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the Bloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car), external vehicle will mount an assault on the land speed record.

Wing Commander Green is writing a diary for the BBC News website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

An ambitious start to the New Year.

A great way to start the New Year

I spent last summer running air operations over Libya, so missed out on our long-planned summer sailing holiday.

As a result, our holiday crew decided to rent a boat and head out over the New Year instead - which was great fun (even in the rain) until the last day, when the storms arrived.....

I've never experienced a 60mph gust while at sea before - the force was truly humbling.

Now that I'm safely back on land, I've had time to think about the gale-force winds.

The power of the wind at 60-plus mph was huge - and that is about one seventeenth the speed of Bloodhound SSC.

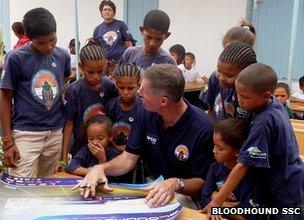

Visiting South Africa – "Bloodhound" is an international language

It's even worse than that, though. Air loads are proportional to the square of the wind speed, so compared to the battering our humble hire-yacht took, Bloodhound at 1,000mph will be subject to about (17x17=) 289 times the aerodynamic force.

I'm glad that we've spent five years on the aerodynamic research, to make sure that it's exactly right - it will need to be.

Of course, we're not the only ones planning to hurl a car through the air at supersonic speeds.

It's an extraordinary time for the Land Speed Record right now, with more teams competing, external for the record than at any time since the 1960s. The slower(!) teams are only building cars for 800mph, aiming to break our current record of 763mph. The other "fast" teams are looking to match our target of 1,000mph.

The good news is that most teams have some sort of education programme, external as well. They've got some way to go to match Bloodhound's current total of over 4,800 schools and colleges taking part, but every little helps - and the sheer variety of cars taking part in this Engineering Adventure, external makes the education story so much more interesting.

Kiwi new boys - Jetblack

The 800mph cars include three US teams: Steve Fossett's old car, which is up for sale, external (and I really hope it sells soon - it would be great to see it run); the North American Eagle, external, a cut-down ex-Nasa jet fighter; and a new bid from five-times World Record holder Craig Breedlove. Two of these cars are pretty much ready to run, so they could produce some exciting results during 2012.

In the fast (1,000mph) category are the rocket cars, led by long-time Australian campaigner Rosco McGlashan and his Aussie Invader 5R, external. Rosco is well into the build of his car, so again we're hoping to see him run within a couple of years.

We don't know much about the prospects for the Australian Silver Bullet or the American Sonic Wind LSRV, external cars, other than they intend to try and go very fast.

Finally, there is a new player on the scene, in the form of the New Zealand Jet Black, external team - another would-be '1,000 miler'.

They have two things in common with Bloodhound.

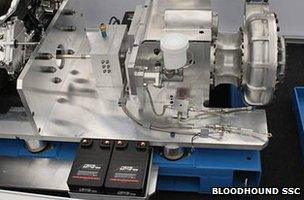

Pump motor – by Cosworth

First, they are also planning to use the benefits of both a jet engine and rocket motors. Second, their driver is an ex-RAF fast jet pilot - so they're bound to do well!

One thing that all the 1,000mph rocket cars have in common is the challenge of developing the rocket technology.

This, in my view, is going to be one of Bloodhound's big challenges for 2012.

We are using a very safe rocket, with non-explosive solid rubber as its fuel and non-explosive (but highly corrosive) High Test Peroxide as the oxidiser.

Making the rocket go involves mixing these two at high temperature and pressure. We have to pump almost 1,000kg of the HTP oxidiser into the rocket at 76 Bar (1000psi) in about 20 seconds.

We expect the pump to take about 700hp to turn it - hence the Cosworth F1 engine being used as a pump motor for Bloodhound.

But now for the uncertainties. We are building the world's most powerful hybrid rocket ("hybrid" means solid fuel + liquid oxidiser), so there is nothing we can really compare this with.

Pump Test Rig – anyone fancy a bet on the exact output pressure?

The chemistry is unique, so we're only estimating the thrust of the rocket motor - we won't know exactly how much pressure the oxidiser will need until we start the test firings in the Spring.

To add some more uncertainty, the pump is also unique, so we don't know exactly how much power it will take - again all we have is a calculated figure, until we start doing things for real.

If everything goes well, then the rocket thrust will match or exceed our predictions and the rocket pump will be at least as efficient as we hope.

If not, then we have some modifications available to increase the power. Alternatively, we can use slightly less power over a longer period of time, modifying the "performance curve" to get to 1,000mph.

We won't know the answers until we do the tests; this is why it's called an Engineering Adventure - uncertainty makes it exciting! Whatever the result, we'll share it with you as soon as we know.

There are a lot of other big engineering challenges to deliver this year - a 1,000mph tail fin (and there's still room to put your name on the fin if you want to support the world's fastest car), 1,000mph wheels and brakes, computer control systems - the list goes on. The excitement of course comes from seeing a virtual car become real after so long spent researching and designing.

I'm particularly looking forward to the rocket tests though. The rocket, too, too has been in development for years and it will be great to have a final solution.

Better still, it's going to be amazing to watch. As impressive as that winter storm? I should think so!

- Published19 December 2011

- Published11 November 2011

- Published10 September 2011

- Published18 May 2011

- Published26 April 2011

- Published5 March 2011

- Published7 February 2011

- Published21 November 2010

- Published13 November 2010