Fishing's global footprint

- Published

- comments

Bluefin tuna - top of the food chain, and top of many people's eating lists

I'm not sure whether logically you can have such a thing as a footprint in water... but if you can, then the footprints of human fishermen now cover much more of the world's oceans than half a century ago.

In a WWF-commissioned report, external out this week, the spread is documented graphically.

The authors, based at the University of British Columbia in Canada, use the concept of "primary production required" (PPR) to illustrate the spread.

The idea is to calculate the proportion of primary production, external - all the chemical energy stored up in living things as a result of photosynthesis - that goes to meeting human needs.

The higher up the food chain you go to find the fish of interest, the more primary productivity you're using. The ones we tend to like eating best, be it tuna, cod or salmon, live at or near the top.

So at different points on the oceans and in different years, you get a variety of numbers, depending on how heavily they're being fished and what type of fish is being taken.

It's quite common now to find that humanity is taking 10%, 20%, even 30% of an area's primary productivity, the study calculates.

This isn't a precise measure of how destructive or sustainable the fishing is in a particular area - you might, for example, take virtually all of a valuable but rare species out of the water and end up with a low PPR value.

But when you read the report's calculations that the extent of ocean at 10% PPR has increased about 10-fold since 1950, that gives you some idea of how industrial fishing has spread across the world.

The spread is shown even more graphically in an animation, external produced along with the report, which shows nations sending ever bigger boats across the high seas to find fish in areas ever more remote from land.

WWF animation showing how fishing has expanded since 1950

Today there is barely an area untouched by fishing.

Regulation of fishing on the high seas has historically been done with the lightest of light touches.

With a few exceptions, the Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs), external, formed of nation states with an interest in the given region, have done very little to stem unsustainable catches.

This is one of the issues that a number of environmental groups are desperate to move up the agenda of the Rio+20 meeting, external later this year, which could see overfishing being discussed by heads of state - a rare opportunity.

Coral reefs, like this one in Irish waters, can be severely damaged by bottom fishing

This push is backed by some European nations, though others are reportedly keen to keep fishing as low on the list of issues as possible.

Given the history of EU fisheries regulation, you might think the bloc is ill-placed to pose as a reformer.

But under its current fisheries commissioner, Maria Damanaki, the European Commission shows many signs of trying to put its historically dysfunctional house in order.

Shortly, it will publish proposals on regulating fishing for deep-sea species in the north-east Atlantic.

Parts of the area in question lies within territorial waters of EU nations, parts lie outside.

Biology doesn't see the boundary - and the commission is proposing therefore that the same regulations should apply inside and outside the demarcation line.

A draft of the proposals that has fallen into my possession shows the commission is explicit in its admission that so far, regulations haven't worked:

"The measures so far taken have not effectively solved the main problems of the fishery, namely:

the high vulnerability of these stocks to fishing

fishing with bottom trawls represents the highest risk of destroying irreplaceable and vulnerable marine ecosystems by fishing gear - the extent of destruction that has already occurred is unknown

fishing with trawls for deep-sea species involves high levels of undesired catch of deep-sea species

determining the sustainable level of fishing pressure via scientific advice is particularly difficult"

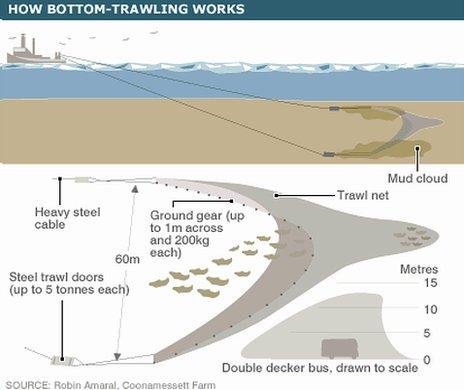

Among the new measures proposed are the phasing out of bottom trawls, the heavy gear that scrapes material from the bottom of the sea - fish, coral and anything else in its way.

In ecologically important areas, it's highly destructive.

Proponents point out that some areas of sea bottom are devoid of anything special and can stand it. The commission's argument is that too often, we don't know what is there before it is too late - and EU nations are committed to using the precautionary principle in such cases.

The commission also wants to see boats carrying independent scientific observers, and would be restricted to landing their catches in ports where inspection facilities are sophisticated enough to deal with the relatively unusual species involved.

Environmental groups are of course urging the commission to go further. And a report this week from the Pew Environment Group, external shows that in one sense, regulating bottom fishing should be very easy.

These species make up only 2-4% of catches globally. They account for about 1.3% of the total value of EU fisheries.

A small economic cost in involved in restricting them, then, for a significant ecological gain.

As with her other proposals for fisheries reform, there's no guarantee Ms Damanaki will manage to get the agreement of the major southern European fishing nations.

And there's no guarantee world leaders in Rio will look at the scientific evidence on industrial fishing and conclude that maybe we really are reaching the end of the line.

But as WWF's animation shows, exploitation of the oceans' riches is now a global phenomenon, and has become so with incredible speed.