America and Eurasia 'to meet at north pole'

- Published

America and Eurasia will crash into each other over the North Pole in 50-200 million years time, according to scientists at Yale University.

They predict Africa and Australia will join the new "supercontinent" too, which will mark the next coming together of the Earth's land masses.

The continents are last thought to have come together 300 million years ago into a supercontinent called Pangaea.

An impression of the "supercontinent of Pangaea" some 300 million years ago

The land masses of the Earth are constantly moving as the Earth's tectonic activity occurs. This generates areas such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where Iceland has formed, and areas such as that off the coast of Japan, where one plate rides over another.

Geologists believe that, over billions of years, these shifting plates have driven the continents together periodically, creating the hypothesised supercontinents of Nuna 1.8 billion years ago, Rodinia a billion years ago, and then Pangaea 300 million years ago.

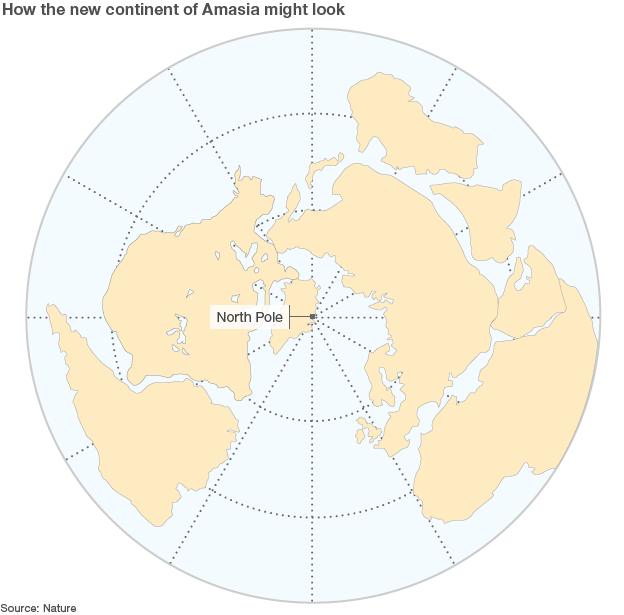

The next supercontinent has already been given the working title of Amasia, as it is expected to involve the convergence of the Americas and Asia.

What the researchers have set out to do is predict when and where it will form by looking back at where its predecessors emerged.

"We're all pretty familiar with the concept of Pangaea, but there hasn't been much convincing data to suggest how the supercontinents take shape," Ross Mitchell of Yale University told BBC News.

"In our model, we actually have North America and South America joining by closing the Caribbean Sea and the Arctic Sea closing and connecting the Americas and Asia."

'Better insight'

The model puts the repositioned Americas within what is known as the Pacific "ring of fire". Europe, part of the Eurasian land mass, Africa and Australia are predicted to join the merging continent, with only Antarctica left out.

The prediction is based on analysis of magnetic data locked into rocks around the world which betray the magnetic orientation of those rocks in past ages.

An animation showing plate motions for the past 500 million years and the rise and fall of the previous supercontinent Pangaea

"Ancient rocks when they form, whether it's lava cooling or sedimentary rock solidifying, will lock in the magnetic orientation," explained Mr Mitchell. "But while this indicates latitude very accurately, historically we haven't had indicators of longitude.

"We found that after each historical supercontinent had assembled, this whole supercontinent would undergo a series of back-and-forth rotations about a stable axis on the equator."

This led them to the view that that each successive supercontinent forms 90 degrees away from its predecessor. Previous studies have suggested supercontinents would form either in the same part of the globe or on alternating sides of the globe.

Commenting on the paper, Dr David Rothery, a geologist with the Open University, said the new research offered us a better insight into the history of our planet.

"We can understand past environments better if we know exactly where they were," he told BBC News. "I don't think as a European I care whether continents are going to converge over the North Pole or whether Britain crashes into America in the far future. Predicting into the future is of far less concern than what happened in the past."

- Published24 March 2011