Drought summit: Why not pipe the water from north to south?

- Published

Reservoirs such as Bewl Water are dry - again

London Mayor Boris Johnson is the latest in a long line of people to wonder why droughts have to be a regular occurrence in the south-east of England, when water is so abundant further north.

Ahead of the drought summit, external, in which the environment secretary is to meet water companies, farmers and wildlife groups, Mr Johnson wrote in the Daily Telegraph, external:"The rain it raineth on the just and the unjust, says the Bible, but frankly it raineth a lot more in Scotland and Wales than it doth in England."

This being the case, he asks why it is not time to "use the principle of gravity to bring surplus rain from the mountains to irrigate and refresh the breadbasket of the country in the South and East".

Piping water from wet north to dry south has seemed like a good idea to a long line of people, most significantly the Water Resources Board, the government agency that used to look after what was then regarded as a national resource.

In 1973, it compiled a major report that advocated all kinds of infrastructure to aid the trickle-down: building freshwater storage barrages in the Ouse Wash and Morecambe Bay, using canals to move water from north to south, extending reservoirs and building new aqueducts and tunnels between river basins.

The Water Resources Board proposed a massive network of aqueducts, tunnels, reservoirs and connections

A year later, the board was disbanded and replaced by regional water management bodies. The regional split was emphasised by privatisation in the 1980s.

"Now, there is no attempt to consider the national resources in a holistic way," says John Rodda, former director of hydrology and water resources with the World Meteorological Organization and now a UK-based consultant.

"There is no national plan, and this is because the emphasis is always on each river basin providing resources that are used in that particular area."

Just 'No'

The north-south issue has never completely gone away, however. It was last considered seriously by the Environment Agency in 2006.

London will need more reservoirs unless rising demand can be curbed

The title of its report, external posed the question "Do we need large-scale water transfers for south-east England?".

And the text gave the answer - No.

It could be done, they said. The most radical scheme would see five parallel pipes constructed, each 1.6m in diameter, bringing water from the northern Pennines to London.

But it would cost between five and eight times more than developing extra infrastructure in the south-east, they concluded.

More limited schemes, short of a full five-bore pipe, would still be more expensive than a combination of new regional reservoirs, local pipes and demand management.

There were also ecological concerns, in terms of what happens when you bring life from one river ecosystem into another, and questions over the energy needed to pump what is a heavy material; but money was the main obstacle.

Privatisation has only made national planning more difficult, with each water company holding resources in its own area for its own use.

Below par

However, the problem of drought is not going away. Currently, swathes of the country from Lincolnshire to England's south coast are either officially in drought or heading towards it, depending on the next few months' weather.

In some places, extraction of water from rivers, lakes and aquifers is already judged by the Environment Agency to be beyond what is sustainable.

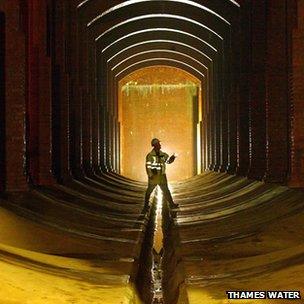

Thames Water, one of the largest UK providers, says that in two of its regions - London, and Swindon, North and South Oxfordshire (SWOX) - demand will outstrip supply for the next couple of decades unless new sources of water are deployed, a situation it manages now by moving water between its regions.

Climate change projections suggest that the south-east will see drier summers and wetter winters.

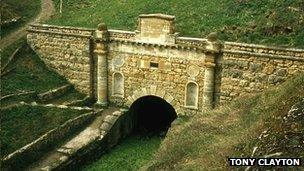

Sapperton Tunnel - at one point the world's longest - could ferry water from Severn to Thames

The extra winter water will not all be captured without new infrastructure, however. So droughts are likely to become more frequent.

Meanwhile, without management, demand will rise. The recent water White Paper, Water For Life, external, said the population of England will rise by just under 10 million by 2035, "with much of this increase likely to be concentrated in areas which are already some of the most water-stressed parts of the country."

That and other demographic changes mean demand could rise by as much as 35% in the next 40 years.

Water companies are attempting to curb demand by increasing the use of water meters, though few make them mandatory.

They are also targeting leakage, which in London still amounts to about a quarter of overall demand.

Some are building new reservoirs, although one of the biggest new projects, a Thames Water reservoir near Abingdon in Oxfordshire, was recently turned down over planning objections.

But Mr Johnson need not give up hope. There are some signs that the beast of national water distribution is not completely vanquished.

The Water White Paper declares: "We want to increase interconnection in our water supply system so that we can use our resources more flexibly and efficiently.

"The Environment Agency will look for interconnection options across all licensed water supplies and will consider further whether there are environmental barriers to large scale transfers through existing river and canal systems."

Severn comfort

One scheme that has stubbornly refused to be ripped off the drawing board is a link between the Severn and the Thames.

It is among the options that Thames Water has considered in recent years, external; and even though there is currently no plan to make it happen, it may become viable, depending on the economics.

China's proposed Water Transfer Project will dwarf even the mighty Three Gorges Dam

In an academic paper, external he wrote a few years ago, Dr Rodda concluded that linking the Severn and Thames basins through the Sapperton Tunnel, a currently disused length of the Thames and Severn Canal, external, could be cost-effective for the southeast - more so than Thames Water's Oxfordshire reservoir plan.

"You would need a flow rate of about two cubic metres per second, and you'd only run it when it was necessary and when reservoir levels in London were low," he says.

"When you consider that the Chinese South-North Water Transfer Project, external will move 2,000 cubic metres per second, that's not a lot."

As the Environment Agency looks for new opportunities to connect, one of the issues it will need to bear in mind is that it is not just the south-east - and not just London - that is feeling the strain.

East Anglia, extending across to Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire, has seen worse drought conditions in recent months than further south.

The county with the biggest rainfall deficit currently is Northamptonshire; even Shropshire is unusually dry. A Severn-Thames link would not help much here.

One aspect of the situation that is often ignored is this: people live elsewhere in the world with a lot less water than southern England receives.

So maybe we just need to recognise that the entire nation is not drowning in the stuff, however much we like to whinge about the grey British weather.

Follow Richard on Twitter, external

- Published20 February 2012

- Published16 February 2012