Cruise finds Fukushima pollution

- Published

Marine organisms were collected for evaluation

Radioactive elements from the damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant have been detected in seawater and marine organisms up to 600km from Japan.

But the scientists who made the discovery stress the natural radioactivity of seawater dwarfs anything seen in their samples.

The results come from a research cruise in June last year, external led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

The initial findings were presented to the biennial Ocean Sciences Meeting, external.

"Just because we can measure radioactivity doesn't mean it's harmful," WHOI's Ken Buesseler told the gathering in Salt Lake City.

"There's a pretty good news story in here - that the levels [of radioactivity] offshore are not of significance to human health in terms of exposure, or even if you were to eat the seafood offshore," he added.

The cruise carried researchers from the US, UK, France, Spain and Japan. Conducted just three months after the Fukushima crisis began, it was intended as an "independent check" on Japanese government-funded research and the information released by Tepco, the owners of the beleaguered Daiichi plant in Fukushima.

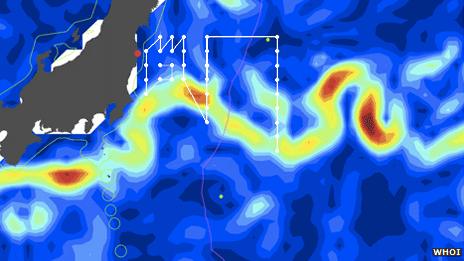

The Research Vessel KOK sailed a zig-zag path from 600km to 30km off the coast, taking thousands of samples of seawater, including the organisms living in it, such as plankton and small fish. It also deployed "drifters" into the water to understand better the behaviour of local currents and eddies.

Analysis revealed elevated levels of radioactive elements that could be tied directly to releases from the nuclear power station.

Ken Buesseler: Our cruise provides crosschecks on Japanese research

These included caesium-137 and caesium-134. Radioactivity readings in the seawater across the track ranged from less than three becquerels per cubic metre up to 4,000 becquerels per cubic metre.

The maximum of these readings is about a thousand times what could be measured in the water prior to the nuclear accident.

Interestingly, the cruise found these highest detections were not in areas sampled closest to Fukushima.

"There was an eddy quite close to the coast that seemed to be trapping water, and had high levels of caesium in it relative to the water that was actually closer to the plant, which had lower levels. It would appear that the circulation was just holding more contaminated water," said WHOI's Dr Steven Jayne, who reported the drifter experiments.

Dr Steven Jayne: Our results should inform Japanese policymakers

Elevated readings were also measured in sampled marine organisms, which can concentrate the contamination relative to the surrounding water.

The researchers who looked at the plankton and fish even detected a radioactive form of silver for the first time in the open ocean.

But again, all measured levels of the Fukushima-related radioactivity were far below that from potassium-40, a naturally occurring radioisotope in the environment.

"The concentration of potassium-40 was five to six times greater than all of the [elements from Fukushima] combined," explained Prof Nicholas Fisher from Stony Brook University.

"So if you add both caesium isotopes and radioactive silver - they represented only one-fifth or one-sixth of the radioactivity contributable to potassium-40."

Dr Nicholas Fisher: The levels from natural potassium-40 are far higher

To emphasise the point, Prof Fisher told BBC News: "I would not hesitate eating any of the organisms we sampled."

The researchers have some qualifications about their own research, the most significant of which is that they were not permitted any closer than 30km to the coast, where higher levels of radioactivity would have been observable.

Although they add their numbers can be used to corroborate data from Japanese-only research conducted directly offshore.

It is clear also, 11 months on from the accident, that Fukushima-originated radioactivity levels in the seawater are not declining as fast as many scientists would have hoped.

"The reactor site still seems to be leaking; it hasn't shut off completely, and at those levels right on the coast you could still have these concentration factors that we measured that would indicate some organisms would be at levels unfit for human consumption," Dr Buesseler said.

The research cruise track and sampling points superimposed on the path of the Kuroshio Current (yellow and red), the dominant movement of water in the region

- Published22 February 2012

- Published22 February 2012

- Published9 February 2015

- Published13 February 2012