Scrutiny for Norwegian fjord rock disposal

- Published

In some fjords, tailings can be extensive enough to break the water surface, producing a kind of "mud flat"

Out of sight, out of mind - but not for much longer.

The practice of dumping millions of tonnes of waste rock in deep Norwegian fjords is coming under close scrutiny from the country's scientists.

The debris, or tailings, from mining operations has been deposited on the seafloor for decades with little recognition of its likely impacts.

Now, the Norwegian Institute for Water Research, external (Niva) is mounting a series of studies to assess the consequences.

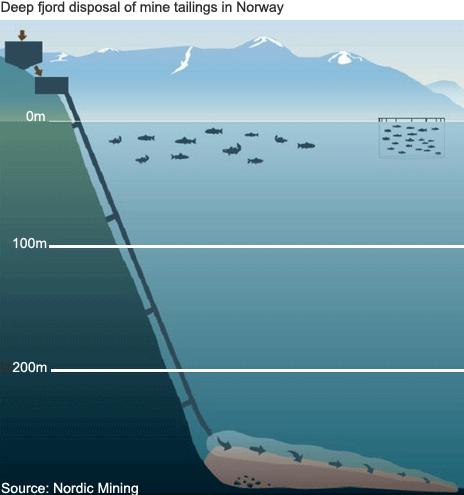

"The mining companies send these tailings down a long pipe, down below the euphotic zone, below 200m, and essentially smother everything on the seafloor," explained Prof Andrew Sweetman, a research scientist with Niva.

"All the animals that live in the sediments that provide food for larger invertebrates and fish, for example, will be killed off.

Prof Andrew Sweetman: 'We're trying to get a better understanding of the impacts'

"Potentially, you are also going to kill off a lot of deep water corals.

"And you can get extremely turbid water columns, and it can stay turbid for long periods of time. So, it's a big deal," he told BBC News.

Prof Sweetman was speaking at the biennial Ocean Sciences Meeting, external in Salt Lake City.

The mining industry is an important sector for the Norwegian economy, employing some 22,000 people.

The project is placing artificial reefs on tailings to encourage organisms to return

Its targets are profitable metals, natural stone and aggregates. Sometimes whole mountains are dismantled in the process.

Currently, there are mine tailings actively being deposited at 23 sites along the Norwegian coast, but there are many licence applications pending.

The waste rock could be stored on land, but it is unsightly and it is also a more expensive disposal option. Companies can save $25m a year with fjord burial.

Very few studies to date have actually assessed the environmental impacts of tailings deposits, says Prof Sweetman, who is also affiliated to the University of Bergen.

The three-year project being run by Niva will try to describe those impacts more fully, but also look at strategies for containment and recovery of the deposits.

"We'll be looking at how the existing deposits are functioning, how they have recovered since the cessation of tailings placements in certain areas," Prof Sweetman explained.

"We're also looking at changes in the mineralogy, the chemical changes, and the physical changes over time.

"We're also running a number of experiments where we're trying to manipulate the organic content - essentially food for marine animals - to assist those animals coming in and recolonising what is a pretty barren under-seascape."

The Niva-led study group is also putting structures on top of the deposits to see if they will act as artificial reefs.

Prof Sweetman detailed the research project during a session at the meeting dedicated to "deep sea conservation imperatives in the 21st Century".

Session chair Prof Lisa Levin, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, said that the Norwegian tailings story was a classic example of an activity being undertaken without fully understanding its consequences.

The deep ocean, she said, was coming under pressure as never before.

"The biggest pressures right now fall into three categories," she told BBC News.

"There's deep-water fishing and the most severe effects of that would be bottom-trawling, which is extensive in certain parts of the world.

"Then there's oil and gas. Industry is moving steadily deeper. Three thousand metres is now routine, and we know what can happen.

"And we're poised to mine in deep water. There are mining interests in manganese nodule fields, massive sulphides which are at hydrothermal vents, and phosphorites for rare earth elements."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published22 February 2012

- Published18 February 2012

- Published7 December 2011