Schmallenberg virus: What, where, how?

- Published

Lambs and calves are born with deformities that vets are trying to quantify through autopsies

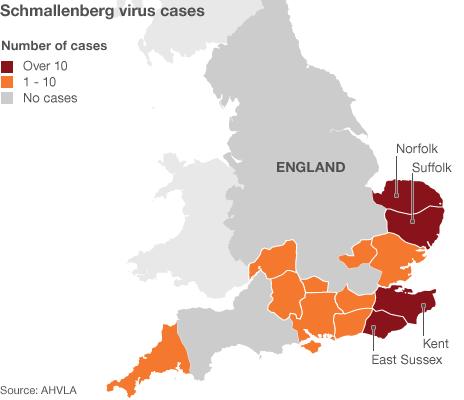

As Schmallenberg virus is confirmed on 83 farms in the UK, our environment correspondent Richard Black looks at what the virus is, what it does and how it can be tackled.

What is Schmallenberg virus?

Schmallenberg virus is a disease of farm animals that was first seen last year in northern Europe. It is named after the German town, about 80km east of Cologne, where it was identified.

Cases have been seen, externalin Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Italy as well as the UK. Incidence in Germany is so far about 10 times the UK level.

It was first identified in the UK in late January.

The virus appears to be a member of theOrthobunyavirus, externalgenus. These are known to cause other animal diseases - some serious, others not so.

Schmallenberg has so far been seen in sheep, cattle and goats, and is thought to be carried by midges.

Orthobunyaviruses easily swap genetic material with each other, and scientists suspect that the new strain arose recently through an interaction between existing viruses that might be harmless.

What does it do to farm animals?

Schmallenberg produces fever, diarrhoea and loss of milk production in adult cattle, though the animals recover after a few days. In adult sheep, infection is apparently symptomless.

However, when pregnant females are infected, the virus can damage the foetus, leading to a range of deformities at birth.

These include malformations of the brain such as hydrocephalus (sacs of fluid), scoliosis (severe curvature of the spine), and the fusing of limbs.

In some German flocks, half of the lambs born show such symptoms, and many are stillborn.

There is no clear picture yet of the economic damage to the UK farming industry.

Does it affect people?

So far, there are no signs that it does. TheEuropean Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDPC) says, externalit is "unlikely that this virus will cause disease in humans, but it cannot be excluded at this stage".

The majority of known orthobunyaviruses are benign in humans, although there are exceptions, such as the California encephalitis virus.

German researchers have already produced a genome sequence of Schmallenberg. It indicates that the virus lacks genetic sequences that would make it a threat to humans.

As a precaution, farmers are being advised to implement strict hygiene measures, and ECDPC advises "close collaboration between animal and human health services" to monitor the health of farmers, vets and other people in contact with infected animals.

How can it be tackled?

Nothing can be done to improve the lot of lambs and calves being born this spring, as their conditions result from infections that happened last year.

The Friedrich Loeffler Institut in Germany has already developed a test for the virus, but it can only be used in the lab. The National Farmers Union is among thosepushing for rapid development of a test, externalthat can be used on farms.

The evidence strongly suggests that Schmallenberg is carried by biting midges. Experience with other insect-borne diseases shows that tackling the vector can be highly effective.

The UK Institute for Animal Healthis working with the Met Office, externalto develop programs to predict the virus's spread, should it be confirmed that midges are the vectors.

Scientists are already working towards a vaccine, but that could take a few years to develop.

Follow Richardon Twitter, external

- Published27 February 2012

- Published23 January 2012