Daunting challenge of Fukushima clean-up

- Published

The clean-up involves removing contaminated topsoil and vegetation

At a site above Oruda primary school on the outskirts of Fukushima city, local council workers and volunteers are engaged in a mass clean up operation.

The work is anything but sophisticated: conventional gardening tools, brush cutters, rakes and brooms are used to move the topsoil ready to be bagged up and taken to the dump site.

This waste is of the low level variety; typical background radiation readings in the area around the school are lower than levels which occur naturally elsewhere in the world. Yet concerns remain.

The clean-up strategy for Fukushima and Date City was devised by Shunichi Tanaka, the former acting head of Japan's Atomic Energy Agency.

"Usually the contamination happened in a nuclear facility, inside a controlled area, but this type of contamination is global environmental contamination - it's completely different," he says.

Fruit and vegetables remain unpicked due to comtamination fears

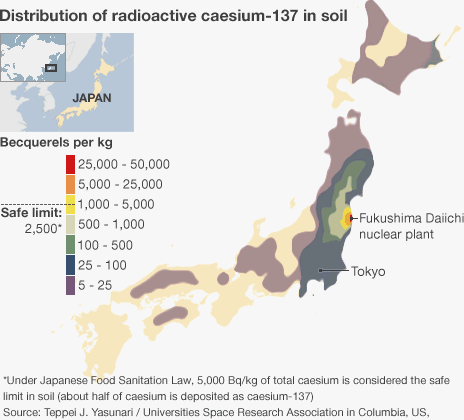

Following the explosions at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant on 11 March last year, wind carried a cloud of radioactive debris off towards the north-west.

This airborne debris fell on populated areas beyond the 20km exclusion zone that would later be set up around the plant.

Soon after the disaster, scientists at Tokyo University's Department of Agriculture and Life Sciences began to analyse soil samples from the area to determine how radiation was spreading.

Prof Tomoko Nakanishi presented their initial findings in the Japanese journal Radioisotopes in August 2011. She says the radioactive caesium does not move very far once it bonds with the soil particles.

"The rainfall was 198mm during the first three months and the caesium... moved 21.6mm (downwards).

"Then in the next three months the caesium moved only 5.6mm - despite the rainfall being three times higher. This shows with time, the caesium was more firmly adhered to the soil."

Grinding concrete surfaces may help, but also risks releasing contaminated dust

The radioactive fallout from the nuclear plant contained a number of radioactive isotopes - products of the nuclear reactions - which differ widely in how long they persist in the environment.

Radioactive iodine decayed to near background levels within a few days, but the bigger concern was over isotopes of caesium, some with half lives of more than 30 years.

The Tokyo University study had shown that caesium was not penetrating very far. It was instead bonding tightly with soil at the surface.

This gave Shunichi Tanaka something to work on for his clean up strategy; he concluded only the upper contaminated soil layer need be removed.

"The most important thing is to remove the surface, for soil one or two centimetres; 5mm to 1cm for concrete and asphalt," he says.

While the caesium forms a tight bond with clay particles in the soil surface, wherever caesium landed on hard surfaces - such as concrete or asphalt - it presented a different problem.

"Its not chemically bonded, it's in a physical trap," says Shunichi Tanaka.

Each school in Fukushima now has atmospheric radiation monitors

The caesium finds its way into tiny pores on the surface, and the only way to remove it effectively is to grind off the surface, a difficult procedure which can create contaminated dust.

Nevertheless, as the soil, asphalt and concrete is removed overall radiation levels should fall. But this does not necessarily mean the threat of exposure has completely gone.

Prof Tomoko Nakanishi acknowledges there might be a small future risk from food, in particular from less well studied areas

"We have to continue these measurements for a long time, we do not know what will happen to the next harvest or the harvest after that," he explains.

"This year perhaps we can get less radioactivity in rice… It takes a year to harvest rice. Contamination is not uniform, some places have very high radioactivity; some people may be growing rice there without realising.

"There is a possibility there might be some contaminated rice coming out."

While the caesium is hard for plants and animals to take up when it is tightly bound to the soil, once in solution (dissolved in water) it can be more readily absorbed.

The scientists are watching closely the effect of melting snow and rainfall leaching down from mountainous areas. They are also concerned this water may bring more dissolved caesium into rice fields in the future.