White-nose syndrome in bats continues to spread

- Published

Despite efforts to control white-nose syndrome, the disease is continuing to spread across the US

A fungal disease that has killed more than 5.5 million bats is continuing to spread across North America.

White-nose syndrome, first recorded in New York in 2006, is now present in 20 states and four Canadian provinces.

Research just published provides further evidence that the disease is caused by the fungus, and that it originated in Europe.

Last year, <link> <caption>researchers and policymakers agreed on a national action plan</caption> <url href="http://www.fws.gov/whitenosesyndrome/pdf/White-nose_Natl_Plan_FS2.pdf" platform="highweb"/> </link> in order to limit the disease's impact.

"We now have 19 states that have confirmed the disease, and one additional state that has detected the fungus that causes the disease," explained Ann Froschauer from the US white-nose syndrome (WNS) co-ordination team at the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

"In addition, we have four Canadian provinces that have also confirmed the disease."

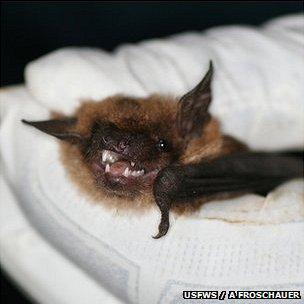

WNS is named after a white fungus that appears on the muzzle and/or wings of infected animals, and has been described by some biologists as the worst US wildlife health crisis in living memory.

Here to stay

"We recognise that bats are moving the disease pretty efficiently themselves," Ms Froschauer told BBC News.

"What we are doing in terms of a containment strategy is to basically buy ourselves some time and prevent a big long-distance jump, such as an accidental introduction of the fungus in an area much further than the bats could naturally move it.

"We don't want someone to hop on a plane in New York and then get off in Seattle and create a new epicentre, so our containment strategy focuses on decontamination protocol and restricting access to sites.

"I don't think we will ever expect to stop this disease in its tracks, but there may be ways to reduce the effects of the disease on the bat populations."

The fungus associated with the disease, Geomyces destructans (Gd), thrives in dark, damp places such as caves and mines.

Recent studies have painted a bleak picture for at least half of US bat species, which rely on hibernation for winter survival and are therefore potentially susceptible to the disease.

Writing in the journal Science in August 2010, a team of researchers warned that <link> <caption>some species' populations could become locally extinct within two decades</caption> <url href="http://www.sciencemag.org/content/329/5992/679.abstract" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

And in April, another team estimated the loss of bat species, which help control pest populations, would <link> <caption>cost US agriculture more than $3.7bn a year</caption> <url href="http://www.sciencemag.org/content/332/6025/41.summary?sid=dbe8e87b-5670-4848-96c6-94c9c5d17c8c" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

A paper <link> <caption>published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences</caption> <url href="http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1200374109" platform="highweb"/> </link> builds on other recent research suggesting that the fungus is found in populations of bats in Europe without triggering mass mortality.

An international team of scientists said their findings showed that a species of bat found in North America developed WNS if it was exposed to either US or European samples of the fungus.

This provided "direct evidence that Gd is a novel pathogen to North America from Europe", they suggested.

Ms Froschauer welcomed the latest development: "We are hopeful that this will help us better understand ways that we could mitigate the effects of the disease.

"It could help us identify the characteristics that are allowing European bats to fight off the disease."

- Published18 January 2012

- Published18 May 2011

- Published24 December 2010