Indonesia's Sumatra alive to quake and tsunami risks

- Published

There is no doubting the people of Sumatra are alive to the risks of earthquakes and the possibility of a tsunami.

News video of panic and shock emerging from Banda Aceh, the provincial capital and largest city in the island's northern province, spoke volumes.

Memories of the big quake in December 2004 (magnitude 9.1), external are still raw.

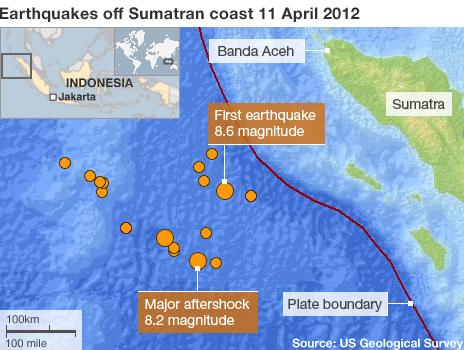

Wednesday's major tremor (M8.6), external occurred in a similar location, although much further offshore (some 400km), at 15:38 local time (08:38 GMT). It was followed by an aftershock of M8.2, external just a couple of hours later.

Tsunami alerts were issued for the entire Indian Ocean basin but, mercifully, the scale of the wave action appears to have been small - on the order of a few tens of cm in height.

"Our tide gauges and buoys recorded small tsunamis," Said Kristiawan, of Indonesia's Meteorology and Geophysics Agency, said.

Underwater landslide

Geologists reported quickly that the quake was "predominantly strike-slip" - that is to say, the movement of rock at the site of fracture was horizontal in nature.

"Tsunami can be caused in a number of ways, but typically it is where the seafloor can be moved vertically, and that displaces a large amount of water that travels outward from that source toward land," observed Bruce Pressgrave, from the US Geological Survey (USGS).

"One of the ways that strike-slip earthquakes can cause tsunami is if the shaking itself causes some kind of underwater landslide that then produces the movement in the water column," he told BBC News.

Nonetheless, the alerts stayed in place for several hours as the authorities attempted to get on top of the latest information, and there is now a lot more of it.

This is one of the big changes since 2004. There is now a tsunami monitoring system dedicated to the Indian Ocean, put in place through the leadership of [UN scientific agency] Unesco in 2006.

Pressure sensors on the ocean floor detect anomalous behaviour in the water column and signal that information to surface buoys, which then relay the data, via satellite, to onshore control centres.

The system is much needed, particularly in Indonesia. Its Sumatra island lies close to an active subduction zone, where the Indian-Australian tectonic plate presses into and under the Sunda plate.

This monumental collision is evident on the ocean floor by a huge depression known as the Sunda Trench.

The slab of cold, dense rock that descends into the Earth at this point gets stuck, and strain builds up that has to be released at some stage in the form of an earthquake.

More aftershocks

But what was key to Wednesday's outcome was that the main event occurred some distance to the west of the Sunda Trench, and so did not produce the very big megathrust action capable of deforming the seafloor in a way likely to generate large tsunamis.

"This is not one of those; it was the seafloor moving horizontally - one part moving relative to the other," explained Dr Richard Luckett, a seismologist with the British Geological Survey.

"What we think this is, is some kind of correction to do with all the massive earthquakes that have happened in the Sunda trench in the last 10 years.

"And so this kind of earthquake, although very big and widely felt, is much less likely to cause a serious tsunami," he told the BBC.

"We're unlikely to get another aftershock as big as the M8.2, although it can happen. But there will be aftershocks - fives, sixes, maybe even sevens, going on for several months."

To put these magnitudes in context: one would expect about two or three quakes a year greater than M8.0 to occur somewhere on Earth. On Wednesday, they had a pair of big ones off the coast of Sumatra.

We await the full impact of these events; power outages mean it will be sometime before the authorities get a complete picture of what happened.

But if there are positives to be drawn, they are that the warning systems and building regulations introduced in recent years will have been extensively tested. Citizens also will have been reminded of the safety actions they must take in the event of big tremors.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published11 April 2012

- Published11 April 2012

- Published22 June 2022