Quantum computing: Is it possible, and should you care?

- Published

"Qubits" can now be made to do their computing tricks in semiconductors

What is a quantum computer and when can I have one? It makes use of all that "spooky" quantum stuff and vastly increases computing power, right? And they'll be under every desk when scientists finally tame the spooky stuff, right? And computing will undergo a revolution no less profound than the one that brought us the microchip, right?

Well, sort of.

That is broadly what has been said about quantum computers up to now, but it's probably best to pause here and be clear about what is, at this stage, most likely to come.

First things first, though: just what do they do? Many media outlets have dived into the academic literature sporadically to shed some light on the effort.

BBC News has reported that quantum computers "exploit the counterintuitive fact that photons or trapped atoms can exist in multiple states or 'superpositions' at the same time, external", and ", external" - plus, other quantum weirdness means the whole business "can then be done 'in the cloud' completely securely".

This week has seen two more advances in the field. In one, a team reporting in Nature, external describes the first fully quantum network, in which "qubits" - quantum bits, the information currency of quantum computers - were faithfully shuttled between two laboratories.

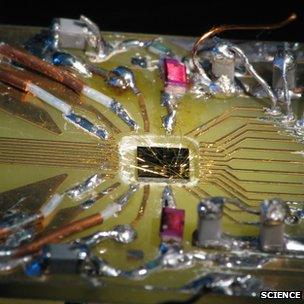

In another, a team writing in Science, external says they have "entangled" two qubits - representing the simplest core of a quantum computer - within a semiconductor, materials that standard computer makers are already familiar with manufacturing.

(It has been truly busy recently; the largest ensemble of working qubits was reported on Arxiv, external in January, and the biggest quantum computer number-crunching feat was published in Physical Review Letters, external in late March.)

Bet it works

It is all a bit bewildering, so to sum up the state of the field: very small-scale, laboratory-bound quantum computers that can solve simple problems exist; most researchers say the idea of massively scaled-up versions looks perfectly plausible on paper; but making them is an engineering challenge that practically defies quantifying.

Scott Aaronson, an expert in the theory of computation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is one believer in the scaled-up quantum computer. He recently offered a $100,000 prize, external for a convincing proof that such a device could not be made.

But he has no illusions that it is just around the corner.

"I get kind of annoyed by all the (popular media) articles reporting every little experimental advance," he told BBC News.

"The journalists have to sell everything, so they present each thing like we're really on the verge of a quantum computer - but it's just another step in what is a large and very difficult research effort.

"It was more than 100 years between Charles Babbage, external and the invention of the transistor, so I feel like if we can beat that, then we're doing well - but that's a hundred years for people to say 'works great on paper, but where is it?'"

More than that, though, even the most optimistic researchers believe that quantum computers will not be a wholesale replacement for computers as we now know them.

The only applications that everyone can agree that quantum computers will do markedly better are code-breaking and creating useful simulations of systems in nature in which quantum mechanics plays a part.

Martin Plenio, director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Ulm, Germany, said that "it might never happen that it will be a device that sits here under my desk".

"A quantum computer can do all the things that a classical computer can do, and some of those things it can do much better, faster, like factoring large numbers," he told BBC News.

"But for many questions it's not going to be superior at all. There is simply no point to use a quantum computer to do your word processing."

Quantum add-ons

Others are more sanguine about the utility of what will come out of the current research efforts.

Alan Woodward, a professor of computing at the University of Surrey, cites a couple of recent advances that, to his mind, signify a significant push toward a computer that might sit under his or Prof Plenio's desk.

Quantum experiments are still complex and bulky lab-based beasts

Most quantum computers to date have been designed to tackle a single problem, unlike the general-purpose computers we use now. But Prof Woodward says that a report in Nature Photonics, external in December represents the first "programmable" quantum computer.

And, he said it is significant that an industry giant like IBM is getting into the game; at a meeting of the American Physical Society in March, IBM researchers reported significant advances, external in just how long they could preserve the quantum information in their qubits.

"Are you going to have a purely quantum computer in five years? No - what you'll have is elements of these things coming out, you always do with technology," he told BBC News.

"In the same way you have a graphics processor card along with a main processor board in a modern computer, you'll see things added on; people will find a means of using quantum computing and the quantum techniques, and that's how I think it'll move forward.

"And those I can definitely see in the five-year period."

Prof Woodward is in the minority in thinking that the consumer market will benefit widely from quantum computers; the problem of course is making predictions about a technology that has, since its inception, always seemed possible but even now is not incontrovertibly achievable.

Dr Aaronson concedes that perhaps the long term may bear out a greater desire and use for it.

"It's hard for me to envision why you'd want a quantum computer for checking your email or for playing Angry Birds. But to be fair, people in the 1950s said 'I don't see why anyone would want a computer in their home', so maybe this is just limited imagination.

"Maybe quantum video games will be all the rage 100 years from now."

- Published19 January 2012

- Published22 March 2011