Key tests in search for life in frozen Antarctic lake

- Published

- comments

The tests will take place in very challenging conditions

Crucial training has begun for a project to search for life in a lake hidden beneath the Antarctic ice-sheet.

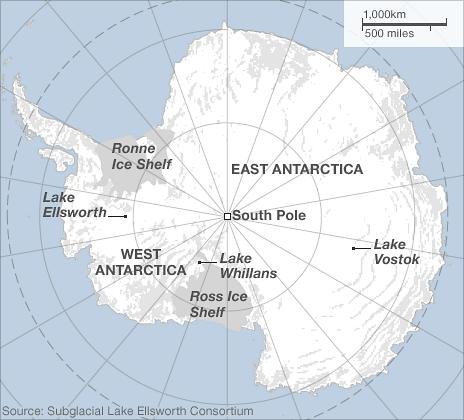

Scientists and engineers are rehearsing the most challenging stages of the drilling operation planned for Lake Ellsworth.

The goal is to gather samples of water and sediment in a hunt for microbial organisms and clues about past climate.

Training is focused on the handling of a water sampling device and a corer to extract sediment from the lake floor.

To avoid contamination, the drilling has to be undertaken in conditions cleaner than those required in an operating theatre.

The rehearsals are taking place at the National Oceanography Centre at Southampton with the team that will be deployed to Antarctica later this year.

The equipment has to remain sterile to avoid polluting the lake - believed to have been isolated for up to 500,000 years - and to preserve the value of the samples.

This level of hygiene has never been attempted before in the exacting conditions of a polar region.

Blasting a hole

The plan calls for a hot-water drill to blast a hole through the two-mile-thick ice sheet within three days.

The equipment will need to be kept sterile

The assumption is that the hole will remain open for 24 hours - allowing a brief window for the different probes to be deployed.

At the quay side in Southampton, a deep storm drain serves as a location for the first tests of the system, and the water sampling device has been lowered inside it.

A specially-adapted shipping container, mounted on rails above the drain, provides shelter and holds the winching mechanism for 4,000m of cable - long enough to reach through the ice sheet to the dark waters of the lake below.

Each component is kept sterile within air-tight plastic compartments tested to withstand the temperatures of -30C expected in the field.

The task of connecting and disconnecting the different probes has to be carried out by reaching into the compartments using in-built rubber gloves - an awkward process in the benign weather of a spring day on the English South Coast, but potentially nightmarish in a punishing wind chill.

First run

In the first run, attaching and lowering the water sampling device took 44 minutes; extracting it took 32 minutes, and the team was reasonably satisfied.

In the actual operation, every minute will count before the drill-hole re-freezes; but working in icy conditions is bound to add delay and complication.

In the first day of testing, the team encountered some teething problems including the design of some of the clamps holding components in position. These can, though, be re-engineered.

According to Ed Waugh, who designed the electronics for the water sampling device, the trials are "a useful way of getting a feel for the task".

Detailed planning includes a step-by-step guide to each stage of the operation - with no fewer than 20 steps for the job of getting the water sampling probe into position, and another 13 to deploy it.

At key points, components will go through further careful cleaning with ethanol and a thorough sterilisation with hydrogen peroxide vapour which, to add to the challenges, has to kept above 15C.

Once the hole has been blasted open with hot water, a probe carrying an ultraviolet light will be lowered to sterilise its upper section.

That will then be followed by the water sampling device - its descent captured live by HD cameras - and then the sediment corer. If time allows, each will be deployed a second time.

All this has to be carried out in the notoriously cold and windy environment of West Antarctica.

The tests will continue at Southampton for several months, culminating in a "dress rehearsal". Then the the equipment will be packed up to be shipped south in August.

Five containers of heavy gear including the hot-water drill were delivered to the lake site earlier this year, where they will stay under wraps through the polar winter.

After 10 years of planning and two years of design and engineering, the project is entering a critical phase.

By the end of the year, if all goes according to plan, we should have the first sight - and the first samples - of a lost world beneath the ice.

- Published16 January 2012

- Published11 October 2011

- Published28 January 2011