Big rise in North Pacific plastic waste

- Published

The Scripps team trawled the surface of the ocean for floating debris

The quantity of small plastic fragments floating in the north-east Pacific Ocean has increased a hundred fold over the past 40 years.

Scientists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography documented the big rise when they trawled the waters off California.

They were able to compare their plastic "catch" with previous data for the region.

The group <link> <caption>reports its findings in the journal Biology Letters</caption> <url href="http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/lookup/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0298" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"We did not expect to find this," says <link> <caption>Scripps researcher Miriam Goldstein</caption> <url href="http://www.miriamgoldstein.info/" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"When you go out into the North Pacific, what you find can be highly variable. So, to find such a clear pattern and such a large increase was very surprising," she told BBC News.

All the plastic discarded into the ocean that does not sink will eventually break down.

Sunlight and the action of the waves will degrade and shred the material over time into pieces the size of a fingernail, or smaller.

An obvious concern is that this micro-material could be ingested by marine organisms, but the Scripps team has noted another, perhaps unexpected, consequence.

The fragments make it easier for the marine insect <italic>Halobates sericeus </italic> to lay its eggs out over the ocean.

These "sea skaters" or "water striders" - relatives of pond water skaters - need a platform for the task.

Normally, this might be seabird feathers, tar lumps or even pieces of pumice rock. But it is clear from the trawl results that <italic>H. sericeus</italic> has been greatly aided by the numerous plastic surfaces now available to it in the Pacific.

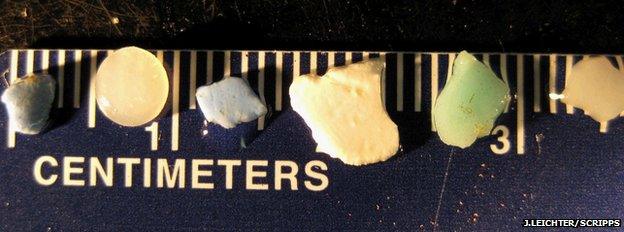

The fragments are tiny - about 5mm in diameter, or less

The team found a strong association between the presence of <italic>Halobates </italic>and the micro-plastic in a way that was just not evident in the data from 40 years ago.

Ms Goldstein explained: "We thought there might be fewer <italic>Halobates </italic>if there's more plastic - that there might be some sort of toxic effect. But, actually, we found the opposite. In the areas that had the most plastic, we found the most <italic>Halobates</italic>.

"So, they're obviously congregating around this plastic, laying their eggs on it, and hatching out from it. For <italic>Halobates</italic>, all this plastic has worked out well for them."

The micro-plastic has been a boon to one marine invertebrate - Halobates sericeus

Ms Goldstein and colleagues gathered their information on the abundance of micro-plastic during the <link> <caption>Scripps Environmental Accumulation of Plastic Expedition (Seaplex)</caption> <url href="http://sio.ucsd.edu/Expeditions/Seaplex/" platform="highweb"/> </link> off California in 2009. They then compared their data with those from other scientific cruises, including archived records stretching back to the early 1970s.

Plastic waste in the North Pacific is an ongoing concern.

The natural circulation of water - the North Pacific Gyre - tends to retain the debris in reasonably discrete, long-lived collections, which have popularly become known as "garbage patches". In the north-eastern Pacific, one of these concentrations is seen in waters between Hawaii and California.

This Scripps study follows another report by colleagues at the institution that showed 9% of the fish collected during the same Seaplex voyage had plastic waste in their stomachs.

That investigation, published in Marine Ecology Progress Series, estimated the fish at intermediate ocean depths in the North Pacific Ocean could be ingesting plastic at a rate of roughly 12,000 to 24,000 tonnes per year.

Crabs, barnacles, sea anemones and hydroids make a home on a piece of discarded rope

Toxicity is the issue most often raised in relation to this type of pollution, but Ms Goldstein and colleagues say broader ecosystem effects also need to be studied.

The abundance of ocean debris will influence the success, or otherwise, of "rafting communities" - those species that are specifically adapted to life on or around objects floating in the water.

Bigger creatures would include barnacles and crabs, and even fish that like to live under some kind of cover, but large-scale change would likely touch even the smallest organisms.

"The study raises an important issue, which is the addition of hard surfaces to the open ocean," says Ms Goldstein.

"In the North Pacific, for example, there's no floating seaweed like there is in the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic. And we know that the animals, the plants and the microbes that live on hard surfaces are different to the ones that live floating around in the water.

"So, what plastic has done is add hundreds of millions of hard surfaces to the Pacific Ocean. That's quite a profound change."

Ms Goldstein's co-authors were Marci Rosenberg, a student at the University of California Los Angeles, and Scripps research biologist emeritus Lanna Cheng.

Debris tends to collect within the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone. Ocean eddies and other small ocean circulation features will further aggregate material into more discrete "garbage patches"

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on <link> <caption>Twitter</caption> <url href="https://twitter.com/#!/BBCAmos" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published19 March 2012

- Published6 October 2010