James Webb telescope's 'first light' instrument ready to ship

- Published

- comments

BBC correspondent Jonathan Amos gets to see the Mid-Infrared Instrument (Miri) close up before its shipment to the US

One of Europe's main contributions to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is built and ready to ship to the US.

The Mid-Infrared Instrument (Miri), external will gather key data as the $9bn (£5.5bn) observatory seeks to identify the first starlight in the Universe.

The results of testing conducted at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK have just been signed off, clearing Miri to travel to America.

James Webb, external - regarded as the successor to Hubble - is due to launch in 2018.

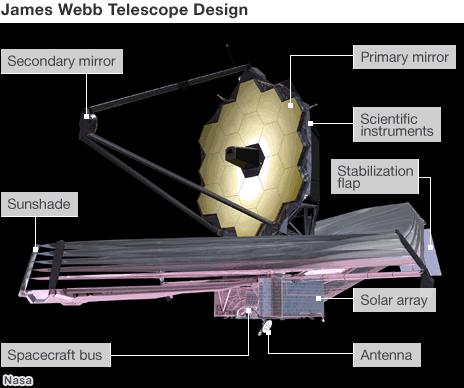

It will carry a 6.5m primary mirror (more than double the width of Hubble's main mirror), and a shield the size of a tennis court to guard its sensitive vision from the heat and strong light of our Sun.

The observatory has been tasked with tracking down the very first luminous objects in the cosmos - groupings of the first generation of stars, external to burst into life.

Prof Gillian Wright: "We can see very red and faint light from distant galaxies"

To do so, Webb will use its infrared detectors to look deeper into space than Hubble, and further back in time - to a period more than 13 billion years ago.

"The other instruments on James Webb, external will do massive surveys of the sky, looking for these very rare objects; they will find the candidates," explained Miri's UK principal investigator, Prof Gillian Wright, external.

"But Miri has a very special role because it will be the instrument that looks at these candidates to determine which of them is a true first light object. Only Miri can give us that confirmation," she told BBC News.

James Webb's main mirror has around seven times more collecting area than Hubble's 2.4m primary mirror

The sunshield is about 22m by 12m. There will be a 300-degree difference in temperature between the two sides

James Webb's instruments must be very cold to ensure their own infrared glow does not swamp the observations

The mission will launch in 2018 on an Ariane rocket. The observing position will be 1.5 million km from Earth

JWST is a co-operative project between the US (Nasa), European (Esa) and Canadian (CSA) space agencies.

Europe is providing two of the telescope's four instruments and the Ariane rocket to put it in orbit.

Miri is arguably the most versatile of the four instruments, with a much wider range of detectable wavelengths than its peers (5-28 microns).

Fundamentally, it is a camera system that will produce pictures of the cosmos.

All of JWST's mirror segments are now complete

But it also carries a coronagraph to block the light from bright objects so it can see more easily nearby, dimmer targets - such as planets circling their stars. In addition, there is a spectrograph that will slice light into its component colours so scientists can discern something of the chemistry of far-flung phenomena.

Miri is a complex design, and will operate at minus 266C. This frigid state is required for the instrument's detectors to sample the faintest of infrared sources. Everything must be done to ensure the telescope's own heat energy does not swamp the very signal it is pursuing.

The hardware for Miri has been developed by institutes and companies from across Europe and America.

The job of pulling every item together and assembling the finished system has had its scientific and engineering lead in the UK.

Miri has just gone through a rigorous mechanical and thermal test campaign at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL) in Oxfordshire.

This included shaking the instrument to simulate the pounding it will receive during the ascent to orbit on the Ariane.

It was also put in a vacuum chamber and subjected to the kind of temperatures it will experience in space.

"It's been a real privilege to work on Miri and great to see it finally ship out," said Paul Eccleston, the engineer at RAL who has overseen the test campaign.

"It will be so exciting when we put it on top of the rocket and light the blue touch paper, so to speak, and watch it go up into space."

The paperwork signing off the test results has now been accepted by Nasa.

The next step is for Miri to be put in a special environment-controlled shipping box, so it can travel to the US space agency's Goddard centre. The Maryland facility is where the final integration of James Webb will take place.

Miri will be fixed inside a cage-like structure called the Integrated Science Instrument Module, external and positioned just behind the big mirror.

The years to 2018 promise yet more testing.

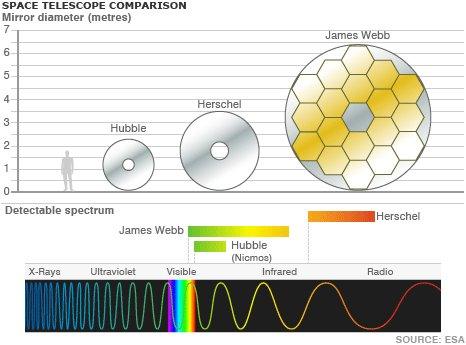

Hubble views some near-infrared wavelengths. James Webb will seek longer wavelengths. Europe's Herschel telescope goes longer still

James Webb's instruments will be tuned to light beyond the detection of our eyes - at near- and mid-infrared wavelengths

It is in the infrared that very distant objects will show up, and also those objects that in the visible range are obscured by dust

Hubble is a visible light telescope with some near-infrared capability, but its sensitivity will be dwarfed by JWST's technologies

Europe's far-infrared Herschel space telescope has a bigger mirror than Hubble, but JWST's mirror will be larger still

Recommended 16 years ago as the logical evolution beyond Hubble, the JWST has managed to garner a fair amount of controversy.

Technical difficulties and project mismanagement mean the observatory is now running years behind schedule and is billions of dollars over-budget.

Elements of the US Congress wanted to cancel the telescope last summer. That did not happen, but Capitol Hill now has James Webb on a very short leash, with Nasa required to provide monthly updates on milestones met or missed.

Much of the talk around James Webb tends to centre on cost. The current estimate for the US side is $8.8bn, which covers the full life cycle of the project from its inception to the end of initial operations. Extra to that bill is some $650m for the European contributions like Miri and Ariane.

Dr Eric Smith is Nasa's deputy programme director for James Webb. He believes taxpayers do appreciate the venture.

"When you're able to show people that James Webb will do things that not even Hubble can do - then they understand it," he told BBC News.

"People recognise how iconic Hubble has been, and how much it has affected their lives.

"The images and scientific results that Hubble has returned have permeated popular culture. Webb pictures will be just as sharp but because the telescope will be looking at a different part of the spectrum, it will show us things that are totally new."

Dr Eric Smith, Nasa's deputy programme director for James Webb, explains what the telescope can do

- Published23 August 2011

- Published18 August 2011

- Published7 July 2011

- Published11 November 2010