Maya art and calendar at Xultun stun archaeologists

- Published

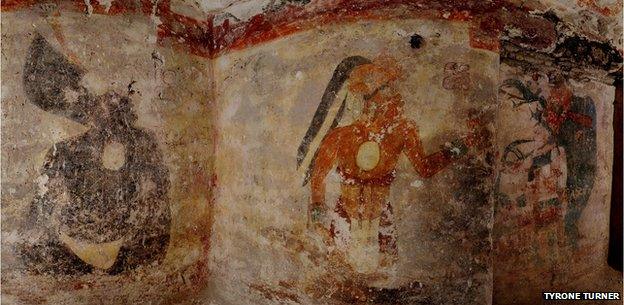

The preservation of the artwork surprised archaeologists, given the dwelling's shallow depth

Archaeologists working at the Xultun ruins of the Maya civilisation have reported striking finds, including the oldest-known Mayan astronomical tables.

The site, in Guatemala, includes the first known instance of Maya art painted on the walls of a dwelling.

A report in Science says it dates from the early 9th Century, pre-dating other Maya calendars by centuries.

Such calendars rose to prominence recently amid claims they predicted the end of the world in 2012.

The Mayan civilisation occupied Central America from about 2000BC until its decline and assimilation following the colonisation by the Spanish from the 16th Century onwards. It still holds fascination, with many early Maya sites still hidden or uncatalogued.

The ruins at Xultun were first discovered in 1912 and mapping efforts in the 1920s and 1970s laid out much of the site's structure.

Three of the four walls of the structure are remarkably well preserved

Archaeologists have catalogued the site's features, including a 35m-tall pyramid, but thousands of structures on the 30 sq km site remain unexplored.

In 2005, William Saturno, then at the University of New Hampshire, <link> <firstCreated>2005-12-14T03:23:04+00:00</firstCreated> <lastUpdated>2005-12-14T03:23:04+00:00</lastUpdated> <caption>discovered the oldest-known Maya murals</caption> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/4526872.stm" platform="highweb"/> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/mobile/world/americas/4526872.stm" platform="enhancedmobile"/> </link> at a site just a few kilometres away called San Bartolo.

in 2010, one of Dr Saturno's students was following the tracks of more recent looters at Xultun when he discovered the vegetation-covered structure that has now been excavated.

When Maya renovated an old structure, they typically collapsed its roof and built on top of the rubble. But for some reason, the new Xultun find had been filled in through its doorway, with the roof left intact.

Dr Saturno, who is now based at Boston University, explained that despite it being under just a metre of soil today, that served to preserve the site after more than a millennium of rainy seasons, insect traffic and encroaching plant and tree roots.

"We found that three of the room's four walls were well preserved and that the ceilings were also in good shape in terms of the paintings on them, so we got an awful lot more than we bargained for," he said.

'Different mindset'

The excavation was carried out using grants from the National Geographic Society, which has prepared <link> <caption>a high-resolution photographic tour of the room</caption> <url href="http://on.natgeo.com/KQHQWq" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

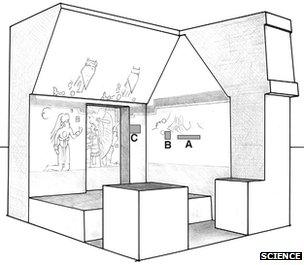

It measures about 2m on each side with a 3m, vaulted ceiling, and is dominated by a stone bench, suggesting the room was a meeting place.

The east wall features a number of seated figures, nearly life-sized, dressed in black and wearing elaborate headdresses similar to a bishop's mitre.

They all look toward the north wall, on which a more elaborately dressed figure in orange holds a stylus in a hand outstretched toward a figure that Dr Saturno believes represented the king of Xultun.

The astronomical cycles and corrections were used to predict lunar eclipses far into the future

"The seated figures that we see around them are involved in some narrative in which the king is being portrayed impersonating a Maya deity and these guys are in attendance at that impersonation," Dr Saturno explained.

The relevance of the figure with the stylus seems clear: "We think this room was used as a writing room, that it's part of a complex associated with the work being done by Maya scribes."

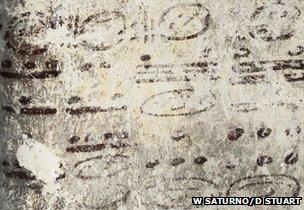

Perhaps most intriguing among the finds were several finds related to astronomical tables, including four long numbers on the east wall that represent a cycle lasting up to 2.5 million days.

The east wall is mostly covered by tabulations of black symbols or "glyphs" that map out various astronomical cycles: that of Mars and Venus and the lunar eclipses.

The wall also features red marks that appear to be notes and corrections to the calculations; Dr Saturno said that the scribes "seem to be using it like a blackboard".

The Xultun find is the first place that all of the cycles have been found tied mathematically together in one place, representing a calendar that stretches more than 7,000 years into the future.

The Maya numbering system for dates is a complex one in base-18 and base-20 numbers that, in modern-day terms, would "turn over" at the end of 2012.

But Dr Saturno points out that the new finds serve to further undermine the fallacy that this is tantamount to a prediction of the end of the world.

"The ancient Maya predicted the world would continue, that 7,000 years from now, things would be exactly like this," he said.

"We keep looking for endings. The Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change. It's an entirely different mindset."

- Published2 December 2011