Amber preserves insect pollen carriers

- Published

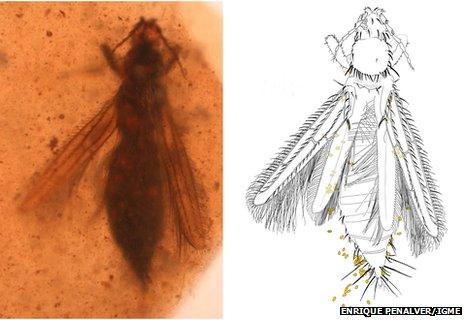

Synchrotron X-ray tomography allows the virtual extraction of the thrips from the amber

What may be the earliest direct example of insect pollination has been identified by scientists.

The evidence is seen in 100-million-year-old amber blocks from Spain that include tiny invertebrates whose bodies are coated with pollen grains.

The role of insects in fertilising plants was one of the great steps in the evolution of life on Earth.

Today, most flowering plants, including many food crops, could not reproduce without the insect transport of pollen.

The discovery is reported in the US journal, the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences (PNAS).

<link> <caption>Amber, the fossilised remnant of tree resin</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/fossils/Amber" platform="highweb"/> </link> , is a wonderful preservation medium, freezing in time the exquisite detail of insects that got caught up in the once sticky mess.

The translucent pieces described by the researchers in their PNAS paper come from the Basque Country.

They contain several thysanopterans, or thrips - slender animals no more than about 2mm in length - and fragments of plant material.

The thrips, like their modern counterparts, would almost certainly have fed on pollen, and the amber-locked specimens have hundreds of grains picked up on their bodies as they went foraging.

One of the amber pieces was examined at the European Light Source (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, and subjected to synchrotron X-ray tomography.

The ring setae with pollen grains attached

This is a technique that allows encapsulated objects to be mapped in three dimensions at very high resolution.

The X-ray imagery reveals the insects to have hairs with specialised structures that would have increased the likelihood of grains becoming attached.

"We also see these ring setae, or ring hairs, in modern pollinators such as domestic bees and some flies," explained Carmen Soriano from the ESRF.

"At very high magnification, we can see that these hairs are mostly in the dorsal part of the thrips and that's also where we observe most of the attached pollen. So, our theory is that these hairs would have been used by the female thrips to gather as much pollen as possible to take back to their larvae."

The team suspects the pollen particles came from a kind of cycad or ginkgo tree. Most probably the latter.

Although there is some indirect evidence from the Late Triassic (200-220 million years ago) that insects were visiting the reproductive parts of plants to eat pollen, the Basque ambers represent perhaps the most compelling example of the transport of pollen by insects.

"To some degree all the evidence we have for insect pollination is indirect because we don't have any insects 'caught in the act', so to speak," conceded Conrad Labandeira from the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

"That would involve finding a structure, an ovule, with a reward such as nectar or pollen, and the insect with its mouth parts preserved inside that structure. That has yet to be found in the fossil record.

"So, we must build a circumstantial case that pollination took place. And I think our ambers are a good bet because we have these structures on the insects' bodies that would only be the most parsimoniously interpretable as structures used for pollination."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on <link> <caption>Twitter</caption> <url href="https://twitter.com/#!/BBCAmos" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published8 September 2011

- Published8 February 2011