Falling stout bubbles explained

- Published

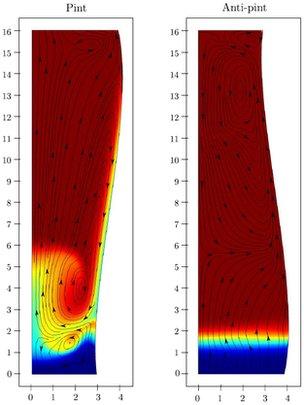

Calculations show that a glass shaped "upside-down" would exhibit the opposite effect on bubbles

Irish mathematicians may have solved the mystery of why bubbles in stout beers such as Guinness sink: it may simply be down to the glass.

Simulations suggest an upward flow at the glass's centre and a downward flow at its edges in which the liquid carried the bubbles down with it.

But the reasons behind this flow pattern remained a mystery.

Now <link> <caption>a study on the Arxiv server</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1205.5233" platform="highweb"/> </link> reports simulations and experiments showing the standard glass' shape is responsible.

Many stout beers contain nitrogen as well as the carbon dioxide that is present in all beers.

Because nitrogen is less likely to dissolve in liquid, that results in smaller and longer-lasting bubbles.

But it is the sinking bubble that has confounded physicists and mathematicians alike for decades.

Like many such "fluid dynamics" problems, getting to the heart of the matter is no easy task; only recently was it <link> <firstCreated>2004-03-16T13:32:54+00:00</firstCreated> <lastUpdated>2004-03-16T13:32:54+00:00</lastUpdated> <caption>proved they actually sink</caption> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/3516100.stm" platform="highweb"/> <url href="http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/mobile/scotland/3516100.stm" platform="enhancedmobile"/> </link> rather than being the result of an optical illusion.

Now the University of Limerick's William Lee, Eugene Benilov and Cathal Cummins have discovered the simple answer to the problem - and a test that can be carried out by consumers as well.

The team has been generally interested in the formation of bubbles in liquids.

"One of the things we found was it's actually very easy to see bubbles forming in stout beer rather than in, say, champagne where the bubble formation process is much more violent," Dr Lee told BBC News.

Drag race

But as has happened to a generation of like-minded scientists before them, the question of falling bubbles became their focus.

The team had the idea - borne out by calculations carried out by Mr Cummins - that the relative density of bubbles and the surrounding liquid could be behind the phenomenon.

A settling pint held at an angle shows both falling and rising bubbles in the same glass

"If you imagine your pint is full of bubbles, then the bubbles will start to rise," Dr Lee said.

But the bubbles in a standard pint glass find themselves in a different environment as they rise straight up.

"Because of the sloping wall of the pint, the bubbles are moving away from the wall, which means you're getting a much denser region next to the wall," Dr Lee explained.

"That is going to sink under its own gravity, because it's less buoyant, and that sinking fluid will pull the bubbles down."

The bubbles, that is, are "trying" to rise, but the circulation that creates drives fluid down at the wall of the glass.

"You'll see sinking bubbles not because the bubbles themselves are sinking, but because the fluid is and it's pulling them down with it."

The same flow pattern occurs with other beers such as lagers, but the larger bubbles of carbon dioxide are less subject to that drag.

Mr Cummins carried out calculations using a simulated pint and "anti-pint" - that is, the upside-down version of a pint glass - showing the effect at work; in the anti-pint, the bubbles rise as expected.

For those interested in experimenting in the pub, the effect can be best seen if a pint of stout is served in a straight-sided, cylindrical glass (not quite filled up).

If the glass is tilted at an angle while the pint settles, the side in the direction of the tilt represents the normal situation of a pint glass, while the opposite side is the "anti-pint" - and bubbles can be seen to both rise and fall in the same glass.