Stockholm: Birth of the green generation

- Published

- comments

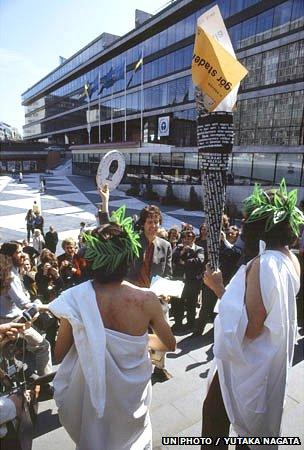

Stockholm was the first UN summit to feature, even welcome, groups from civil society

Stockholm, 1972. Five years after the Summer of Love, four after the Paris riots; the Cold War is in full swing.

The Club of Rome, external has just projected a future in which the demands of a growing human population outstrip the Earth's capacity to provide.

The blue whale, the biggest animal that ever lived, has been hunted almost to extinction.

Atom bomb tests, external continue to garnish the world in strontium-90; and from Japan to Europe to North America, man-made poisons are affecting plants, animals and people.

Economically, the world has never had it so good. But governments are beginning to realise that nature is paying a price.

On 5 June 1972, in the Swedish capital, they began to build their response, in the form of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, external - the first UN summit on the environment, and the event that really put the issue on the global political agenda.

Outside the negotiations, two entirely different groups had also assembled, with a self-appointed brief of keeping the negotiators on track.

One was a small group of scientists who were becoming desperately concerned about population growth, pollution and rapidly increasing use of natural resources.

The other was a much larger gathering of people from what we would now call civil society, or environmental campaign groups, who used the now familiar smorgasbord of marches, song, demonstrations and dialogue to press issues from pollution control to civil rights to vegetarianism.

"My motivation was the message from Rachel Carson and her book Silent Spring, external," recalls Jan-Gustav Strandenaes, one of the 10,000 or so making up the Peoples' Forum.

"It brought together a number of issues we'd read about but not really thought about: the Minamata disaster, external in Japan where all these people were killed by mercury poisoning in water and fish, and there was a similar one in Sweden where they had hormone-disturbing liquids buried in the ground contaminating the fresh water.

"I was looking at these as isolated incidents until I read Rachel Carson's book."

Silent Spring showed how wildlife was being decimated by dangerous chemicals

Silent Spring's main thrust was the damage being wrought on American wildlife by the indiscriminate use of newly invented herbicides and pesticides.

But the wider narrative it told, encompassing Minamata and other incidents, was of human technology running out of control.

The issue was elevated by the appearance in Stockholm of people who had survived the Minamata disaster - the poisoning, the physical and mental symptoms and the corporate cover-up - and by veterans of the war in Vietnam, where the US military's use of defoliant chemicals such as Agent Orange, external sought to destroy a guerrilla army by ripping out forests and fields, at a huge cost to people's health.

The legacy of Agent Orange continues to affect Vietnam - and the US has yet to pay compensation

The involvement of this nascent people's movement in a UN summit was unprecedented.

Although the Swedish government and the conference organisers officially welcomed the Peoples' Forum, it is clear that not all government delegates knew what to make of it.

But inside the official negotiations, many delegates offered a similar message.

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi told the conference: "It has been my perception that people who are at cross purposes with nature are cynical about mankind and ill at ease with themselves.

"Modern man must re-establish an unbroken link with nature and with life."

But developing countries - which had just acquired a new champion with the accession of China to the UN (at the expense of Taiwan) - raised another set of issues that almost ended the summit before it had begun.

"Developing countries were considering boycotting the conference," recalls Maurice Strong, external, the Canadian-born environmental diplomat who chaired the Stockholm summit for the UN.

"They thought this new concern of 'environment' was one for the rich and would distract from their main concerns, which were the relief of poverty and continuing development."

National and factional politics also surfaced in several guises.

Most obviously, the Soviet Union and its allies stayed away, as communist East Germany did not have a seat at the UN table. That meant only 113 nations were present.

The other superpower, though, was very much the focus of attention - particularly when Sweden's Prime Minister Olof Palme raised in dramatically undiplomatic terms the US actions in Vietnam, which he termed "ecocide".

"The indiscriminate bombing, the large-scale use of bulldozers, the use of herbicides, is an outrage," he said.

"Our experience is that the active use of this ecological warfare is coupled to a passive resistance even to discuss it."

In Stockholm, the US remained resistant to discussing it. But in alliance with some of the campaign groups, it found a way to deflect the negative press it was receiving on the issue, by focusing on whaling.

The US had by then stopped its own commercial whale hunts - so had its allies, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands. The only two countries carrying on were the USSR and Japan - which happened to be, respectively, its main political and economic rivals.

Despite the fact that whaling had not been raised as a major issue in documents governments had prepared leading up to the conference, a resolution was passed calling for a moratorium on commercial whaling - which is possibly the outcome that commanded most headline inches.

Maurice Strong, in 1972 and today

It may have been ecologically justified - but there is little doubt that the main motivation was political, at least on the governmental level.

It was not, however, the most profound outcome.

One concrete move was the decision to establish a United Nations Environment Programme, external.

But more significant, in the long term, was the new philosophy evident in the final declaration, external; that nations had to work together on environmental issues, and that a healthy environment was essential for the long-term prosperity of developing countries.

For the first time, governments acknowledged that technology could seriously damage the environment.

They agreed that each country had a duty not to pollute others, and that threatened species needed international protection.

Not everyone was happy. The eminent US biologist Barry Commoner, external, for example, argued that the conference declaration did not go far enough; rather than agreeing to monitor pollution, he said, governments should have been discussing how to develop industries that produced no pollution in the first place.

But Jan-Gustav Strandenaes recalls that on a political level, the impact of the Stockholm agreement - made, as has become customary, in painfully long overnight negotiating sessions - was immediate.

Establishment of the UN Environment Programme was a key Stockholm outcome

"No country in the world had a ministry of the environment before Stockholm; and I know that the Norwegian delegation raced back to Oslo and established a ministry, and they beat the Swedes by a few weeks.

"So Stockholm started something; it put the environment on the political agenda."

Internationally, that agenda would lead in 1987 to the Brundtland Commission, external and its famous definition of a sustainable society as one that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".

It would lead to the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, external in 1992, which gave birth to UN conventions on climate change, biodiversity and desertification, and the Agenda 21 "roadmap" to sustainable development.

The next milestone is also in Rio - the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, nicknamed Rio+20, external - which is scheduled to bring about 130 world leaders as well as ministers, diplomats, business moguls and an estimated 70,000 activists to Brazil later this month.

And many would argue that the need for decisive action is bigger than ever. Governments have done many things since Stockholm to alleviate poverty and stem environmental decline; but still, a billion people live in hunger, and damage to nature progresses.

Now 83, and still very much involved, Maurice Strong has mixed views on whether this month's Rio summit will bring profound change.

"I am analytically pessimistic; I believe we are in danger of not doing what we must do for the survivability of human life and its sustainability," he says.

"But I am operationally optimistic, because as long as there is hope - and there is still hope - we must continue to work for it."

With thanks to Soundings of the Planet, external for use of archive material