Shortages: Water supplies in crisis

- Published

Most countries will have to make do with the water they've got, but there are stark disparities

Over the past 40 years the world's population has doubled. Our use of water has quadrupled. Yet the amount of water on Earth has stayed the same.

Less than 1% of the water on planet blue is for humans to drink.

About 2% is locked up in ice. The rest is for the fish.

Seawater is only good to drink for humans who live near the sea and can afford the cash and the energy to take out the salt.

For most of the population this is not an option.

Desalinated water costs maybe 15 times more than regular water. It burns polluting fossil fuel energy, as solar-powered desalination is in its infancy.

No, most places will have to live with the water they've got.

Many countries are awash; they'll be fine. Others are desperately mining fossil H2O that seeped into rocks during the last ice age.

And as underground supplies run dry, water shortage sets in.

Large parts of Africa, Asia and Europe, including the south east of Britain are categorised by the UN as facing water stress or scarcity.

And for all the UN's recent boast about hitting drinking water targets, experts estimate that <link> <caption>maybe three billion people worldwide</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-18020432" platform="highweb"/> </link> still lack safe water to drink.

And it might get worse with climate change, although scientists' projections of future rainfall are notoriously cloudy.

The global capital of water shortage is Sana'a in Yemen. It's a city of two million people who fight to get water from tankers by the jerry can. Their boreholes are running dry.

But this water crisis like so many others is an act of man not an act of god.

Because, as in most developing countries, 90% of water is used for agriculture, in Yemen, much of it to grow the stimulant qat.

Sana'a in Yemen is one of the most water-stressed cities in the world

And experts insist that if farmers had used water more carefully there would still have been enough to go round.

If countries like Yemen are to tackle their water shortages they will need more skill in politics than in cloud-seeding.

Sustainable water depends on several factors: establishing with people who owns the water; who will pay for it and how much; and that the water is finite and therefore has to be limited.

In many places, people also have to accept that water is the ultimate recyclable resource and re-using it is the only choice.

Upstream privileges

The politics stretches from macro to micro. Many countries dependent on shared rivers like the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mekong.

In an ideal world, the mountainous up-river nations where the rain falls would use it for hydro-electric then send it downstream to grow crops on the fertile plains in a neighbouring land.

Desalination is only an option for a small proportion of the world

But this isn't an ideal world and often the up-river nations simply hog it and try to grow crops inefficiently themselves. The UN has proved mostly powerless to intervene.

At a micro level, there's often an intractable unhealthy embrace between land, money and power. In many developing countries farmers grab 90% of water supplies and hold politicians in thrall.

In a future of water security they'll have to pay the proper amount for the water they use.

Australia has led the way with water trading. The water in the rivers of the Murray-Darling basin has been turned into a tradeable commodity.

Paying by the gallon focuses the farmer's mind on water saving technology. But even that isn't enough. The World Bank says if farmers install water-saving drip-feed technology they simply irrigate more land unless politicians find the courage to tell them that water is limited.

Thirsty lawns

Even America is having to deal with the notion that you can't always get everything you want. Las Vegas pays people to dig up their thirsty lawns forever. But water rationing schemes immediately face political flak.

In the UK, civil engineers want to introduce a sliding tariff so people who water their lawns or their cars pay much more than others who just want to shower, cook and drink with their H2O.

Sometimes it takes a crisis or perception of a crisis to unlock the politics.

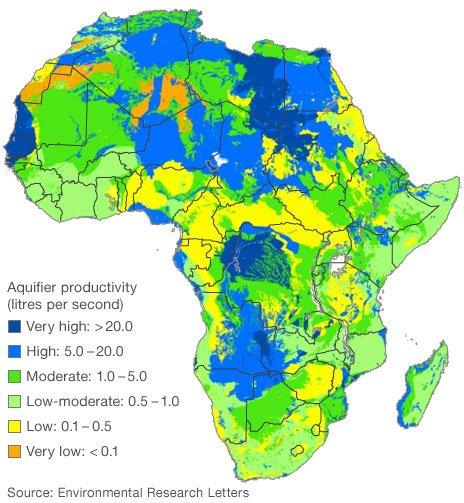

Africa is sitting on a large resource of groundwater, but a change in mindset may be required to unlock it

When Japanese troops invaded in Singapore they blew up the pipes bringing water from Malaysia. The Singaporeans have been jumpy about water ever since and have overcome objections to recycling their water - the so-called toilet to tap method long adopted in Europe.

Technology has helped before and will again. Three thousand years ago, India started installing a system of ponds and tanks to capture monsoon rains and allow them to replenish aquifers below. Many are now being repaired.

Future technologies include new forms of osmosis systems for desalination; GM microbes to help turn sewage back into drinking water; and new strains of seeds that don't require so much water in the first place.

Countries may have to run into crisis before the politics unjams for many of these solutions. But the solutions are there. For most places on the planet, a water crisis is eminently avoidable, if we can find the cash and particularly the resolve to do it.

- Published29 September 2010