Rio: So much to do, so little time

- Published

- comments

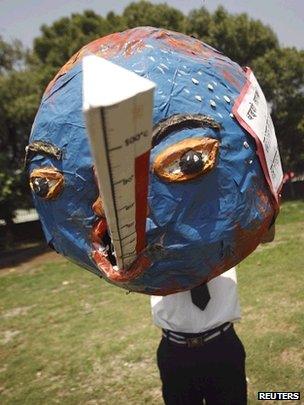

The summit may see conflicts between aims to reduce poverty and make society more sustainable

Along with thousands of government delegates, activists, academics, business chiefs and other journalists I'm making my way this week to Rio de Janeiro.

The event is the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, external, better known as Rio+20.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called it, external a "once-in-a-generation opportunity to make real progress towards the sustainable economy of the future".

Other descriptions range from a "milestone opportunity, external" to cut poverty and protect the economy, an agenda laden with "greenwash, external" and a "farce, external".

It promises to be a busy time for all, especially for government negotiators.

Their job this week is to knock the draft text into a near-finished state, so ministers can come in next week, sign it off and head for the airport looking like they've accomplished something worthwhile.

Currently, the text is far from finished.

An extra negotiating session convened in New York that ended on 2 June has resulted in a document that is only about 20% agreed; and many of the divisions that remain are anything but trivial, resulting from fundamentally different views about how the world should be.

What makes things more complex is, as I've discussed before, the varied nature of the agenda, ranging from high seas protection to universal access to clean energy to corporate sustainability reporting.

The text as it existed at the end of that New York session fell into my hands last week (The Guardian has helpfully posted it, external).

It's riddled with brackets and phrases such as "Iceland delete; Nigeria retain", indicating that minds are a long way from meeting.

While many observers are concerned about the lack of progress, they're also concerned that the only way for everybody to get out of Rio on schedule will be to agree something completely anodyne.

As Jim Leape, head of WWF, put it recently, external: "We are facing two likely scenarios - an agreement so weak it is meaningless, or complete collapse. Neither of these options would give the world what it needs."

In terms of what various countries and blocs are pushing for and against, there are positions you probably wouldn't find that surprising.

The phrase "US delete" leaps out at the reader, so consistently does it appear - often in company with Canada - particularly on anything relating to "common but differentiated responsibilities", the phrase that basically means rich and poor countries both have an interest in solving something but have different roles to play.

The United States, of course, is concerned above all not to give anything to China.

But there are other US positions that ask broader questions. It doesn't want the text to endorse the 2C target for climate change (in which it is backed by Russia) or the principle that countries have a right to develop.

It is against the notion that each government must respect others' sovereign rights over their natural resources, and against the idea of committing to free the world from poverty and hunger - only "extreme" poverty and hunger should be included, it says.

Some governments are concerned about climate change's impacts on food and water supplies

The G77/China, external group of 131 developing countries wants financial support. It wants western governments to re-commit to their target of giving at least 0.7% of their GDP in overseas aid - a promise that few are fulfilling.

It is against clauses that recognise corruption as a block to human progress, and those that commit to phasing out fossil fuel subsidies.

It doesn't want the UN to establish a unit that would argue for the rights of future generations, and is blocking bits of text enshrining gender equality.

There's an almightily convoluted section of the text with more brackets than a home-made bookcase on reforming how the UN deals with sustainable development, which would involve somehow modifying the existing Commission on Sustainable Development, external.

And there are disagreements on the notion of sustainable development goals (SDGs), external.

The idea is for governments to agree in Rio on a process to draw up seven or eight goals that would improve things such as access to food and water while protecting the environment.

These would come into effect in 2015 when most of the existing Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), external expire.

The problem is that there is already a process up and running to agree further MDGs. Development agencies are deeply concerned that the core agenda of improving health and education, alleviating poverty and increasing access to water and sanitation may suffer as a result of having the SDGs as well.

And what of the rich? As I discussed a few weeks ago, does it make any sense to commit to increasing people's wealth and therefore consumption in poor societies without simultaneously working out how to curb over-consumption in countries that already have enough to go round, given that what we collectively consume has to come from the same single planet?

There's been talk of having something along these lines in the SDGs. But the phrase "US delete" stalks the paragraph.

So; a lot to be done in just three days of preparatory talks towards an agreement that the UN says should deliver The Future We Want.

I'll be doing my best to make sense of it for you.