Rio heads for economics with meaning

- Published

- comments

Plantations produce wealth - GDP goes up - but it doesn't catch the costs of environmental damage

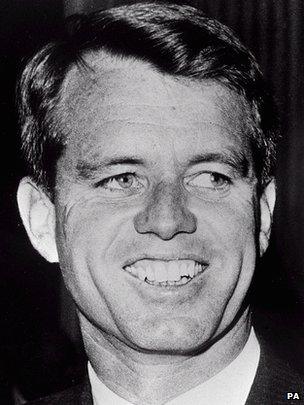

In 1968, with the war in Vietnam at its height and the US psyche in consequent turmoil, senator and presidential hopeful Robert F Kennedy mounted a coruscating attack on one of the sacred cows of economics.

"It counts napalm and the cost of a nuclear warhead, and armoured cars for police who fight riots in our streets," he told an audience, external at the University of Kansas.

"It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programmes which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

"Yet... it measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country.

"It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile."

The target of the senator's ire was Gross National Product (GNP), the dominant indicator of US economic well-being.

Forty-four years later, little has changed. Politicians now generally use Gross Domestic Product (GDP) instead of GNP, but it's a technical difference.

If it goes up even by a fraction of a percent, we're supposed to rejoice - the economy is growing and all is right with our world. If it goes down, faces fall - the economy's shrinking - and the bells of doom start to clang.

Some economists have long questioned whether GDP is measuring anything meaningful. And in recent years, enough governments have listened that the issue is now on the agenda of the Rio+20 meeting, external.

The text in the draft agreement here - which may or may not be agreed, of course - reads:

Robert Kennedy decried the indiscriminate nature of GDP just before his assassination

"We recognise the limitations of GDP as a measure of well-being and sustainable development.

"As a complement to GDP, we resolve to further develop science-based and rigorous methods of measuring sustainable development, natural wealth and social well-being, including the identification of appropriate indicators for measuring progress... [and] use them effectively in our national decision making systems to better inform policy decisions."

So what's wrong with this simple concept whose rise and fall has come to dominate our news headlines?

"GDP is quite simply a measure of all the money we spend on all the stuff we buy - every financial transaction that takes places in the economy, all that adds to growth," says Andrew Simms, external, a fellow of the New Economics Foundation (Nef) and author of several books on the subject.

And it is the indiscriminate nature of GDP that gives him, as well as Robert F Kennedy, a problem.

"Say you had a crime wave, and everybody felt insecure and rushed out to buy more locks for their windows and doors; that would look good on the balance sheet, but it wouldn't tell you the story that something bad was happening in society."

IN GDP-world, a society that drives is richer than one that cycles, as more money is spent.

The faster that mobile phones are traded in for new models, the richer we are; chopping down a forest adds to the national economy. The more alcohol, cigarettes and petrol that are sold, the better off we are.

Criticisms of GDP include:

it measures "bad stuff" as well as "good stuff"

it's a short-term balance sheet that pays no heed to longer-term factors such as a build-up of debt

it takes no account of "natural capital" - the goods and services that nature provides for free

it takes no account of social factors such as how happy people feel

Defenders of the status quo point out that it was never meant to measure environmental or social well-being.

But by dint of being measured constantly and referred to constantly by politicians, business leaders and newspaper editors, others would argue it has become society's weather vane - just about the only simple number in daily use that can be cited as evidence that things are getting better or worse.

Organisations such as Nef have developed composite indicators that they believe are more comprehensive and more valid.

The European Commission has put together a handy compendium, external, listing and explaining concepts such as the Genuine Progress Indicator, Environmentally Sustainable National Income and the Happy Planet Index.

The tiny South Asian nation of Bhutan famously uses the Gross National Happiness indicator, external, which combines issues such as children's health and educational status with measures of environmental protection, cultural values and good governance.

But many other countries are starting down the same road.

Oxford University economist Dieter Helm, external has just been appointed to lead the UK's Natural Capital Committee, external.

Its role is to assess the financial worth locked up in trees, clean water, insect pollinators and every other part of the ecological kingdom, and present this set of accounts to the Treasury - which should then be able to make better informed decisions.

It's worth recalling that the UN-backed Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (Teeb) project calculated, external the value of forest lost globally around the world at $2-5 trillion (£1.3-3.2 trillion) each year.

The costs of the UK not investing North Sea oil revenue were not captured in GDP figures

But Prof Helm also hopes to shine a light on other questions.

"If you peel back and ask 'how well have we been looking after our assets in the British economy?' rather than just saying 'has GDP gone up or down a bit?', we'd have to ask some difficult questions.

"Why did we use up all the North Sea oil and gas [revenue] for the benefit of just one generation? Why did we set nothing aside for future generations? Why haven't we been maintaining our roads and railways properly?"

The implication is that an indicator more sophisticated than GDP should catch such things.

Not everyone is convinced by the arguments for going "beyond GDP".

"Everybody knows that the GDP figures are not perfect," says Lord Lawson, external, Chancellor of the Exchequer under Margaret Thatcher.

"But nevertheless they are extremely useful, and anybody who tried to pretend they were not useful I think would be laughed at."

And he has little time for natural capital accounting.

"It is all a lot of nonsense, because there is no way that you can introduce objectivity into this and it is just used for political campaigning of one kind or another - you just make it add up to whatever you would like it to add up to."

So far, most governments are with Lord Lawson; GDP remains the economic indicator that makes newsreaders sound happy when it rises by half a percent and funereal when it falls. Bhutan is in the minority.

But ministers in Rio will be reminded of the words of Simon Kuznets, the economist who invented GNP 80 years ago: "The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income".