UK laws 'spurring trade in endangered species'

- Published

Sgt Ian Knox shows some of the exotic animal products seized by the Wildlife Crime Unit

"Confusing" UK laws are spurring the trade in endangered species, a wildlife charity has said.

Unhelpful legislation and inconsistent sentencing have helped make London a hub for the £13bn business, they say.

Police have also spoken out about the confusion and have been giving evidence to MPs, who are seeking to clarify the regulations and increase penalties.

Current rules require that police consult a veterinary surgeon if they seize furniture made from rare trees.

In the building that houses the stores of the Metropolitan Police in London sits a grisly collection of animal parts confiscated from the illegal trade in endangered species.

Among the ivory tusks, stuffed tigers and bear skins, Sergeant Ian Knox, who heads the Wildlife Crime Unit, unzips a plain looking holdall to reveal the white head of a fully grown polar bear - now turned into a dead eyed rug.

"We seized this near Portobello Road some years ago - the owner said it was in his possession for 25 years, but when we analysed the plywood on which the head is mounted we found it had been made at most two years previously."

Inconsistent sentencing

Such clear cut cases are a rarity in this business. The laws pertaining to the trade in endangered species are often archaic and confusing. Sergeant Knox recently told the House of Commons environmental audit committee that he was advised to take a vet when inspecting a shipment of furniture made from Brazilian rosewood, a rare species that has been protected since 1991.

"It's not until the enforcers try to make the laws work that sometimes we find there are anomalies. The drafters just forgot to say only live species and only animal species," he explained.

It is not the only area for concern in the current UK laws. Simon Pope is the head of external affairs for the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA). The charity provides funding to the Metropolitan Police wildlife crime unit.

"It's a crazy situation - animals are being imported, being seized by the authorities - but they have to remain in the UK until the case comes to court. It would be a much better idea to repatriate the animals - you don't have to produce a dead body in court to prove a murder," Mr Pope said.

The Environmental Audit committee has now finished hearing evidence and is set to report in the Summer.

As well as archaic and unhelpful regulations, UK legislation is a "complete mess" when it comes to penalties say campaigners. They argue that Home Office guidelines on sentencing for wildlife crimes have never been issued.

"Inconsistent sentencing makes policing a random exercise." Simon Pope told BBC News.

"One judge is lenient, another Draconian - I hope the House of Commons committee will recommend serious changes and we will get some action."

According to WSPA, confusion in the laws and inconsistent sentencing has helped make London a global hub for the trade in threatened species.

"Criminals have seen this and made good use of it. The problem is that this is still perceived as a niche activity.

"This is not a few Arthur Daleys down the market selling turtles, this is people with connections to organised crime in Russia, Japan and Colombia."

Marmite factor

At the Metropolitan Police stores, Sergeant Knox shows me a horn from a black rhinoceros, brutally hacked away from the animal's head.

He says that trading in illegal products like this is more lucrative and less risky than dealing in drugs or guns. Rhino horn can sell for around £60,000 a kilo - around twice the value of gold.

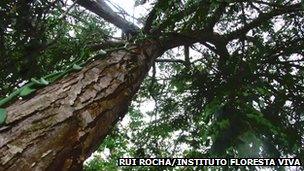

Police need to consult with a vet when seizing products from the Brazilian rosewood tree.

Much of the demand for rhino horn comes from traditional Chinese medicine. As the Chinese community has grown in London over the past decade, so too has the demand for a connection with home.

"We call it the marmite factor," said Simon Pope, "It's the things we miss when we're abroad - it's a desire for those links with home, be it food or medicine, and having the money to be able to afford it."

Another compounding factor that is helping the boom in endangered species is the pressure on police resources.

According to Sergeant Knox, the Met's wildlife crime unit has been cut by 25% since 2009. The police say the funding they receive from WSPA has helped plug the gaps caused by cutbacks.

"Clearly we have to make decisions on priorities." said Sergeant Knox.

"If someone is dealing in ivory or dealing in tiger skins, clearly tigers are more endangered so that's the one I would deal with first.

"We are very rarely faced with having to let that crime go."

A previous House of Commons committee in 2004 failed to update the laws. Simon Pope hopes they manage it this time.

"We can't let this situation continue or it will lead to the decimation of entire species. It doesn't need huge amounts of financial resources, it's the mindset that needs changing," he told BBC News.

- Published19 June 2012

- Published30 January 2012

- Published21 September 2010

- Published16 August 2010