Rio +20: Joining the ecological dots

- Published

- comments

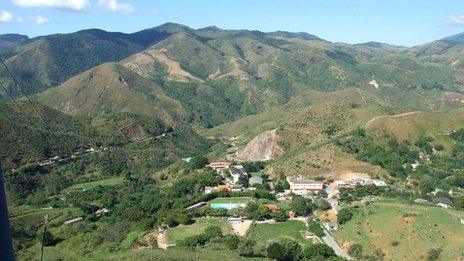

Much native forest has vanished but reforestation is creating new opportunities

The first European visitors to what are now Brazilian shores 500 years ago encountered not an impenetrable forest of jargon, as do visitors to Rio+20 today, but a physical forest of vast scale.

It's hard to credit now, in the age of Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, superhighways and cattle ranching, but the Atlantic Forest once covered more than 1m sq km (385,000 sq miles).

It governed the coast from Recife down through Uruguay and into Argentina, and stood as far inland as Paraguay.

Now, just tiny fragments remain, totalling about 4,000 sq km - struck down, as Maurizio Ruiz tells me, by coffee, charcoal and cattle.

"The coffee plantations came first, in the 1800s," he says; "and what wasn't destroyed by coffee was destroyed by the charcoal industry."

Now, as in the Amazon, cattle ranches have carved out new homes - aided in recent decades by the government, which saw forest simply as land that could be cleared and settled and used for an economic activity.

Lonely tree

Stand on the roadside outside the small town of Miguel Pereira, an hour or so north of Rio de Janeiro, and the problem is clear as the sunny day.

The far-off hills are covered in dense forest. But on the slopes immediately below us, it's a different picture.

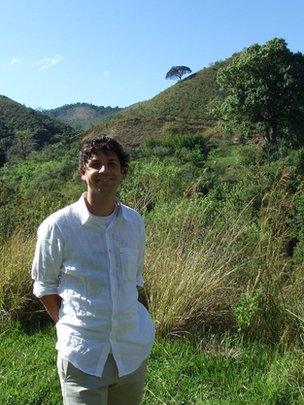

Mauricio founded his tree planting organisation at the tender age of 14

Grass, fences, a few rather scrawny cattle, the fraying relics of abortive eucalyptus plantations, a rather inviting swimming pool; just the occasional lonely tree still stands.

And as the valley bottom holds a stream, this land clearance isn't entirely legal.

Under current laws, landowners have to keep 20% of their territory under tree cover. Land within 20m (65ft) of a river has to stay forested, as do mountaintops.

The clean-shaven ground here is a problem for any wildlife that might have lived in the forests that once grew here.

But ironically, it's providing a window of opportunity for an organisation that wants to plant trees - ITPA (Instituto Terra de Preservercao Ambiental), the organisation that Mauricio founded 16 years ago, at the tender age of 14.

"When I was a kid, I used to run in the field and I used to think about doing this," he says.

He wanted to reforest the denuded lands but also to provide continuing employment for people who worked as itinerant labourers or farmhands - or as tree-fellers.

Now, ITPA employs about 130 people all year round and a few more during "restoration season", September to November.

Slow-release moisture

By the side of a grassy track, 52-year-old Sebastiao - he doesn't give his surname - is planting yellow lapacho (aka ipe-roxo) saplings.

It's a simple business.

A hole is dug; some hydrogel - water plus a polymer - is put in the hole to provide slow-release moisture during the dry season. The sapling follows, and the roots are covered with soil; that's it.

"When I started, I didn't know anything about planting trees, I only knew about cutting them down, burning them," says Sebastiao.

"Then, I was working on a farm and I heard about these jobs.

- What is the Rio summit about?

"Now, I adore the work - it's been a school to me. I never worked in a legal way with documents before."

The reason behind ITPA's continued existence is that for various reasons, people need trees planted.

If landowners want access to credit, subsidies and grants available for protecting watercourses, they have to stay within the forest law. ITPA can plant enough trees on their land to bring them into legality.

The law says that if a company wants to fell one hectare (2.47 acres) of forest for whatever reason, it has to plant five hectares somewhere else.

ITPA is happy to help them.

People and nature

Ecologically, the goal is to connect the dots - to join the still-forested fragments in the area north of Rio, known as the Tingua-Bocaina Biodiversity Corridor, in order to provide a piece of forest and a wildlife habitat big enough to form a meaningful ecosystem.

A patchwork of tiny fragments doesn't maintain itself as forest nearly as well as a large expense; it's more prone to drying out, for example.

A fragment may be too small to support native animals. Even if a few do live there, they can't cross to other areas, leading to inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity.

The golden lion tamarin, ITPA's executive assistant Juliana Bustamante tells me, needs a corridor about 40m wide; with that, it'll travel.

People need trees planted for a variety of reasons, including access to credit and subsidies

Up in the hills, far away from the RioCentro convention complex where government negotiators pore over brackets square, round and curly, ITPA is acting out a central theme of the Rio+20 vision: that the interests of people and nature are not that different.

From here flows the Santa Ana river, a major water source for the teeming millions of Rio.

The authorities spend half a billion dollars each year cleaning up soil that's been washed into the water when rainwater courses down denuded slopes.

Plant the trees, secure the soil, and you save the money, while simultaneously giving people employment and securing the future for animals like the golden lion tamarin.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is taking an interest in ITPA because it sees the group as a living example of the green economy in action.

"IUCN along with other partners has launched a target to restore 150 million hectares [globally] by 2020," says forest and climate chanage specialist Carole Saint-Laurent.

"We've done some analysis and have discovered that if we were to restore 150 million hectares, this would generate for local communities more than $84bn (£53bn) per year in net economic benefits.

"Well, you can't be more relevant than that to the agenda at Rio+20."

Forest Code

On the road back to Rio, we stop underneath a spectacular old iron railway bridge - "the first curved iron bridge in the world," Mauricio informs me, with some pride.

But the real pride lies in the forested strip along the river that the bridge straddles.

Planted just three years ago, the forest now teems with life. Trees are at least 6m high, including one with a trunk covered in thorns and another whose crushed leaves smell just like garlic. Insects are everywhere, including several trying to burrow under my skin, and birds caw in the background.

On the hillside above, a few cattle peer down on us with cud-chewing distain.

ITPA hasn't finished, not by a long way. It's re-forested about 800 hectares so far, but the immediate ambition is 18,000.

The controversial recent revisions to the Forest Code, the national law, may yet slow the demand for planting, as they relax the constraints on landowners.

But international money may start to flow through the UN's REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) scheme.

Future visitors to Rio will never see the Atlantic Forest in its former full glory; that's impossible.

But they way find enough to give a glimpse of what life was like here before the coffee and the charcoal and the cattle came.