Dinosaur cold-blood theory in doubt

- Published

One of the strongest lines of evidence that dinosaurs were cold-blooded, like modern reptiles, has been knocked down.

Prior studies of dinosaur bones uncovered what are known as "lines of arrested growth".

The creatures were presumed to be cold-blooded because modern cold-blooded animals show these same lines.

But scientists <link> <caption>reporting in Nature</caption> <url href="http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature11264.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> have studied the bones of 41 modern mammal species from around the world, finding every one had these lines as well.

The idea that dinosaurs are cold-blooded, or ectothermic, goes back to the 19th Century. But a number of discoveries 1960s have been challenging that notion.

Because soft tissues such as organs and skin are not preserved ( <link> <firstCreated>2011-03-23T01:56:21+00:00</firstCreated> <lastUpdated>2011-03-23T01:56:21+00:00</lastUpdated> <caption>with a few notable exceptions</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-12816862" platform="highweb"/> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/science-environment-12816862" platform="enhancedmobile"/> </link> ), much of what is known about dinosaurs must be inferred from their bones, and comparisons made with modern animals that can be studied in greater detail.

Lagging behind

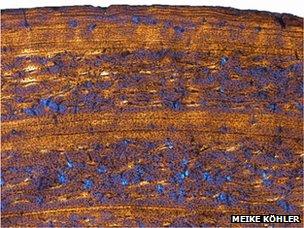

Lines of arrested growth, or Lags, occur because organisms tend to suspend their growth and rally their resources during seasonal periods of environmental stress such as cold or dry conditions.

This forms a boundary from one season to the next as growth resumes when conditions are more favourable.

Lines of arrested growth were found in mammals irrespective of environment, from Svalbard reindeer...

They are familiar in creatures such as molluscs, whose slow annual accumulations can be seen as ridges in their shells.

Lags have also been found in the bones of reptiles and amphibians and have until now been assumed to be limited to ectotherms - cold-blooded animals - that are more subject to the whims of harsh environments.

Meike Koehler of the Catalan Institute of Palaeontology in Barcelona and her colleagues were therefore surprised by what they found.

"Originally this was not a paper that we aimed to do," Dr Koehler told BBC News.

"We were very curious to know how environmental conditions and changes affect bone growth in fossil and extant mammals, to get a good idea about... how they may have coped with these changes in the past."

As the team studied the thigh bones of animals from all over the world - ranging from the Svalbard reindeer in the Arctic to muntjac deer species from South Asia - Lags showed up in every one.

"These lines of arrested growth have been used a lot in dinosaurs, but nobody has ever had a really deep look at mammals," Dr Koehler explained.

....to muntjac deer of South Asia and beyond

David Weishampel, a palaeontologist at the Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Maryland called the new work "a wonderful paper" and said it was a welcome addition to the debate.

"I think most (palaeontologists) regard dinosaurs as being [warm-blooded] but there's a lot of waffling in the data that appeared before that wasn't conclusive," he told BBC News.

"It's about time we have a connection between the modern bone histology and fossil bone histology, through a very nice ecological and metabolic comparison."

While Prof Weishampel considers it a closed case, Dr Koehler herself is more reserved about the result.

"I don't think that this debate is really settled," she said. "But this is the first time that you can say that Lags do not say anything about warm- or cold-bloodedness."

She and her team will go on and put the Lags to use in studies of modern animals instead.

"It's like dendrochronology - the rings in trees. You can do skeletal chronology in bones and infer things like longevity, age at maturity, juvenile states - traits which are very, very important to get an idea about the health of a population and whether it is vulnerable.

"It is very good to know now that mammals do show these Lags and we can use them in the same way that we do in amphibians and reptiles to understand the situation of a population."