China in space: Running fast to catch up

- Published

- comments

Back on Earth - China's first female astronaut Liu Yang smiles for a nation

The smiles said it all. Jing Haipeng, commander of the Shenzhou-9 crew, was the first to emerge from the return capsule, followed by his flight engineers, Liu Wang and the country's first woman astronaut, Liu Yang. Job well done. But their grin is shared across the whole Chinese nation today.

The cost of human spaceflight is so high that you really only go in for this type of ostentatious expenditure if you think you can carry it off, and the Chinese have done that with aplomb these past few days.

The Shenzhou-9 mission posted a series of firsts. Liu Yang's presence in orbit obviously caught the headlines, but I was thinking more about the engineering milestones: the first manned automatic and manual dockings; the first long-duration spaceflight; and the first crew to live aboard a permanently orbiting module, Tiangong-1.

Don't forget also that Jing Haipeng became the first astronaut veteran - this was his second trip into space.

Yes, China is merely repeating the achievements of American and Soviet astronauts made way back in the 1960s and 1970s, but that heritage and the sophistication of modern technology means the Asian nation is on an accelerated development track.

Beijing has long talked about its three-step strategy.

China has learnt its engineering from the Russians

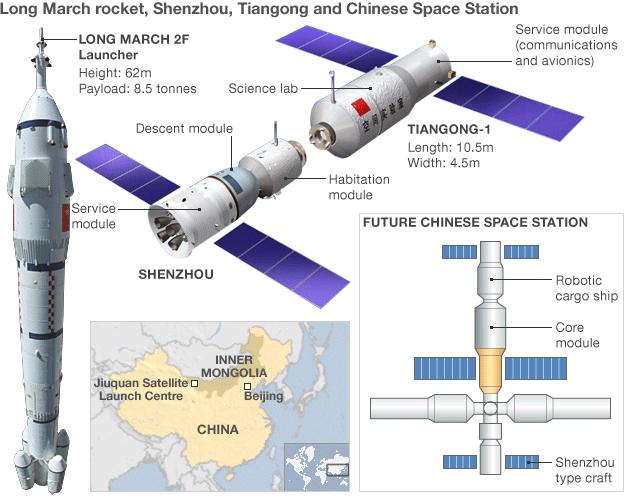

The first step was the development of the Shenzhou capsule system itself - the means to get its astronauts into space. Eight nationals have now taken that journey since 2003.

The second step - which is where we are today - involves the technologies needed for spacewalking and docking. All that leads to the third step - China's own space station.

At about 60 tonnes in mass, this future platform would be a sixth of the mass of the international station operated by the US, Russia, Europe, Canada and Japan, but its mere presence in the sky would be a remarkable achievement.

China still has much to do before it can get itself into that position, however. It needs a bigger rocket for one thing.

The Long March 2F which launches the Shenzhou and Tiangong vessels does not have the capacity to loft the type of modules China would want to incorporate into its station.

The Long March 5 now in development and due to debut in 2014 will significantly boost lifting capacity to low-Earth orbit.

Chinese TV has carried extended live coverage of the Shenzhou-9 mission

It is designed to carry up to 25 tonnes just a few hundred km above the Earth, more than adequate to loft the 20-22-tonne core module envisioned for the prospective space station.

And then there is the steep learning curve associated with understanding just how you live and work in space for long periods. I am talking here about the unglamorous stuff - managing and recycling resources like water and air, and staying fit and healthy in what is a very testing environment. The ISS partners now have a deep knowledge base on these topics.

There has been a lot of talk about China becoming involved in the ISS project itself, and the fact that it has adopted many Russian engineering standards would certainly make it technically possible for Shenzhou vehicles to visit the orbiting complex.

Europe, too, has argued that additional partners could help spread the cost of running what is an extremely expensive endeavour. But political differences between China and the US would appear to make such involvement unlikely in the near-term.

China also has something to prove to itself and the rest of the world, so it is in no hurry to join that particular club. But do expect closer ties to develop.

Do expect Chinese astronauts to turn up at European astronaut training facilities, and vice-versa. And do expect China to fly more and more European experiments on Shenzhou and Tiangong missions.

The German space agency (DLR), one of the "big two" in European space, is already pushing forward on a programme of scientific co-operation.

The aspect of all this that still makes me sit up slightly is the increasing openness now shown by the Chinese.

For example, I watched extended live coverage of the Shenzhou-9 mission in my living room in the UK via the English-speaking version of CCTV, the state broadcaster.

On launch day, the live studio programme went on for about five hours, with studio guests and reporters on the scene at the Jiuquan spaceport on the edge of the Gobi desert.

It was just as if I was watching the rolling news output of the BBC or CNN. Remember that just a few years ago, China would only announce something it had done in space after the event. It is one more sign of extreme confidence, of course.

But a word of caution. Spaceflight, to quote the old cliche, is hard, and at some point the Chinese programme will encounter problems.

The history of spaceflight tells us unfortunately that some adversity is inevitable. It will be interesting then to see how the Beijing authorities react.