Higgs excitement at fever pitch

- Published

Professor Jim Al-Khalili explains what the Higgs boson is and why its discovery is so important

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) are expected to reveal the strongest evidence yet for the Higgs particle in Geneva shortly.

Anticipation is high and rumours have been rife about the announcement.

The Higgs boson would help explain why particles have mass, and fills a glaring hole in the current best theory to describe how the Universe works.

The strength of the LHC's signal is understood to be just short of the benchmark for claiming a "discovery".

But it will show that researchers are now tantalisingly close to confirming the Higgs' existence and bringing to an end the decades-long quest for the most coveted prize in physics.

The $10bn LHC is the most powerful particle accelerator ever built: it smashes two beams of protons together at close to the speed of light with the aim of revealing new phenomena in the wreckage of the collisions.

Massive problem

But why has so much time and effort been invested in detecting the boson?

"The Higgs boson gives other particles mass, which sounds simple," Tara Shears, a particle physicist at Liverpool University, told BBC News.

"But if particles didn't have mass, you wouldn't have stars, you wouldn't have galaxies, you wouldn't even have atoms. The Universe would be entirely different."

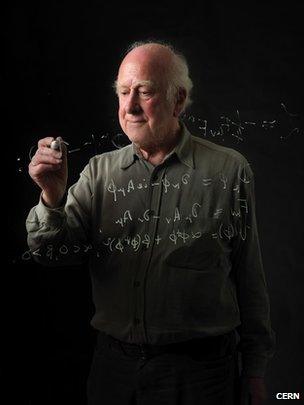

Along with five other theoreticians, Peter Higgs predicted the particle in the 1960s

Mass is a measure of how much stuff an object - such as a particle or molecule - contains. If it were not for mass, all of the fundamental particles that make up atoms would whiz around at light-speed and the Universe as we know it would never have clumped into matter.

According to the theory, all of space is filled by a field - known as the Higgs field, which is mediated by particles known as Higgs bosons.

Other particles gain mass when they interact with the field, much as a person feels resistance from the water - drag - as they wade through a swimming pool.

The boson is the last missing particle in the Standard Model, the most widely accepted theory of how the cosmos works. But the Higgs remains a theoretical construct that has never been observed in a particle accelerator.

Four of the six theoretical physicists credited with coming up with the Higgs mechanism in the 1960s - including Prof Peter Higgs, after whom it is named - have been invited to Cern in Geneva for the presentations, fuelling anticipation of a major announcement.

Unconfirmed reports suggest that the signal detected at a mass of 125 gigaelectronvolts (GeV), which was announced in December, has since strengthened.

"We now have more than double the data we had last year," said Cern's director for research and computing, Sergio Bertolucci.

"That should be enough to see whether the trends we were seeing in the 2011 data are still there, or whether they've gone away. It's a very exciting time."

Momentous time

Discovering particles is a numbers game, and scientists analyse many events that could be representative of a Higgs boson being produced in the LHC.

The hints of the Higgs revealed in 2011 had a statistical certainty of just two sigma.

Three sigma represents about one in 700 likelihood that a "bump" in the data is down to some statistical fluctuation, in the absence of a Higgs. But the benchmark for a discovery is five sigma, denoting a one-in-3.5 million likelihood that a result is down to such a fluctuation.

Rumours suggest the certainty level has now crept beyond four sigma. This might not be enough to announce that scientists have found the elusive particle. But it would suggest the LHC's scientists are within touching distance, and several physicists privately say that such a signal is now unlikely to go away.

Also, the idea that some systemic error could affect all the experiments that see hints of the Higgs - including those at the LHC and the US Tevatron machine (which search for the particle in different ways) - seems just as improbable.

But if and when a new particle is discovered, it will not be clear straight away that it is the Higgs. Physicists will need to characterise its properties in order to confirm whether it is the version of the Higgs predicted by the Standard Model, a "non-conformist" Higgs that hints at new laws of physics, or something else entirely.

This will involve years of detailed and difficult work, said Dr Tony Weidberg, a University of Oxford physicist and member of one of the LHC's experimental teams, Atlas.

He told BBC News that even at a certainty level of five sigma, "you're very far from proving it's a Higgs particle at all, let alone a Standard Model Higgs".

Dr Shears explained that particle physics had seen nothing like this present phase of exploration "in 40 years".

Compared with previous particle accelerators, she said, "the LHC does have that power, that [large] amount of data generated, that precision".

"Everything is coming together to achieve this moment."

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on <link> <caption>Twitter</caption> <url href="https://twitter.com/#!/rincon_p" platform="highweb"/> </link>

- Published2 July 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published4 July 2012

- Published7 March 2012

- Published13 December 2011