Whales snared in ocean debris

- Published

- comments

How many whales are snared and killed by fishing gear and ocean debris each year? No-one knows for sure - but the number entangled is probably huge, and the number dying significant.

Over the past few years, the International Whaling Commission (IWC), external has been starting to address this issue more seriously than before.

At this year's annual meeting in Panama City, I caught up with David Mattila, who's on secondment with the IWC from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) in the US.

Noaa already has a specialist whale freeing team in place, and has even celebrated its work in video, external.

It all began in the late 1970s with Canadian Jon Lien, who started to free whales caught up in fishing gear off the Newfoundland coast.

David Mattila takes up the story:

"Where I started was in New England a couple of years later. Most of our whales were swimming, and actually it was an old-timer, a fisherman who'd hunted a few whales in the past, who suggested we try 'kegging' them, which is attaching our own rope and attaching buoys and maybe even being towed in a boat to keep them at the surface and slow them down."

The point is that if you can do this, you stand a much greater chance of being able to cut the animals free of whatever they're entangled in.

David and his colleagues have developed a few specialised tools of the trade.

One is a grapple that's thrown on the end of a rope, designed so that when it snares the rope already on the whale, it automatically latches on.

Two types of knife are used, both with a V-shaped blade that cuts as it pulls back, so the whale shouldn't be harmed.

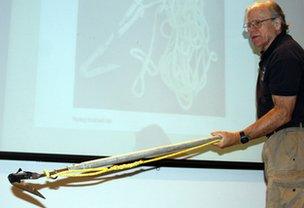

David Mattila demonstrates the equipment used

One is on the end of a pole - the disentangler hooks it around the rope that's snared the whale, pulls back, and cuts the rope

The second is a "flying knife" on the end of a rope, with the other end is attached to a buoy, or maybe the boat, generating a backwards pull, that will eventually cut the rope off and free the animal.

David is now unequivocally a specialist in the art of disentangling whales, his team having freed 1,000 over the years.

Around New England, where he works, 60-70% of right whales and humpbacks show scars typical of entanglement. These ones, of course, have survived and somehow thrown off whatever it was that snared them; how many do not is unclear.

What is clear is that it's not just an issue off the east coast of North America.

Data collected from researchers who have studied humpbacks all over the Pacific showed that in no population were there fewer than 20% that carried entanglement scars; and for most populations, the figure was much higher.

Recently, the IWC decided to start spreading the word and the skills.

A series of workshops has been convened. In March, the show went to Peninsula Valdes in Argentina, a major site for the southern right whale.

David Mattila talks to Richard Black about freeing whales trapped in fishing gear

One of the people there was Miguel Iniguez, a scientist with the NGO Fundacion Cethus, external. Some of the session was very practical, he recalls: "Where to stand in the boat, where the rope must be thrown, whether the engine must be kept on."

But more than that, scientists, conservationists, fishermen, vets and others are now thinking about the issue - about how to build a co-ordinated system that can respond to entangled whales, and more importantly, how to stop them being entangled in the first place.

"The ultimate solution is prevention," says David Mattila. "That's the best thing for fishermen and the best thing for the whales."

That might mean different fishing gear. In Maine, for example, lobster fishermen who traditionally left loops of floating rope between their pots now have to use a rope that sinks to the sea bed, reducing the chance of entanglement.

A "flying knife" cuts ropes without harming the entangled whale

Curious whales have been known to entangle themselves in boat moorings. One solution could be to persuade owners to encase the rope in a stiff plastic sheath - at least for part of the year - that can't be twisted round.

The next part of the IWC plan is to hold a couple of workshops in the Caribbean in a mix of languages. Asia and Africa may follow.

The fact that the IWC is starting to look at this kind of conservation issue rather than just whale hunting has been quietly praised by a number of conservation groups, and by governments that have been encouraging it develop along these lines.

The US and others have put money into the organisation specifically for this kind of project. And it's finding common ground with pro-hunting Norway as well.

David Mattila's last word on disentangling whales is a cautionary one; don't try it yourself. Whales are wild animals, massively stronger than a human being, and may be spooked by attempts to help, especially when people jump in the water to do it.