Graphene holes 'heal themselves'

- Published

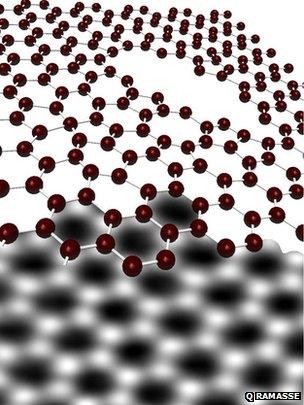

Graphene forms in a neat sheet of interlocked six-sided figures just one atom thick, but is easily damaged

Graphene - the "wonder material" made of sheets of carbon just one atom thick - undergoes a self-repairing process to correct holes, researchers report.

Graphene's outstanding mechanical strength and electronic properties make it a promising material for a wide range of future applications.

But its almost ethereal thinness makes it easily damaged when working with it.

The study, <link> <caption>published in Nano Letters</caption> <url href="http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nl300985q" platform="highweb"/> </link> , suggests it can be repaired by simply exposing it to loose carbon atoms.

It was carried out by researchers at the University of Manchester, UK - including Konstantin Novoselov, who <link> <caption>shared a Nobel prize</caption> <url href="http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2010/" platform="highweb"/> </link> as graphene's co-discoverer - and at the SuperStem Laboratory of the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council in Daresbury, UK.

The team was initially interested in the effects of adding metal contacts to strips of graphene, the only way to exploit its phenomenal electronic properties.

The process routinely creates holes in the atom-thick sheets, so the researchers were trying to understand how those holes form, firing electron beams through graphene sheets and then studying the results with an electron microscope.

But to their surprise, they found that when carbon atoms were also near the samples, the atoms snapped into place, repairing the two-dimensional sheet.

"It just happened that we noticed it," said co-author of the study Quentin Ramasse of the SuperStem laboratory.

"We repeated it a few times and then tried to understand how that came about," he told BBC News.

The team found that when metal atoms were around, they too would snap into the edges of the holes, and when carbon was around as part of molecules called hydrocarbons, the carbon atoms from them could form irregular shapes in the sheets.

But pure carbon atoms would bump metal atoms out of the way, perfectly repairing the holes and forming a fresh and uninterrupted lattice of hexagons - textbook graphene - as they report in <link> <caption>an online preprint of the article</caption> <url href="http://arxiv.org/abs/1207.1487" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

"If you can drill a hole and control that 'carbon reservoir', and let them in in small amounts, you could think about tailoring edges of graphene or repairing holes that have been created inadvertently," Dr Ramasse said.

"We know how to connect small strips of graphene, to drill it, to tailor it, to sculpt it, and it now seems we might be able to grow it back in a reasonably controlled way."

- Published27 January 2012

- Published8 April 2012

- Published3 October 2011